Indicator bacteria

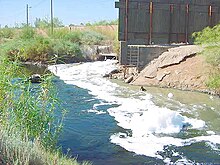

Fecal material can enter the environment from many sources including waste water treatment plants, livestock or poultry manure, sanitary landfills, septic systems, sewage sludge, pets and wildlife.

These organisms can be identified based on the fact that they all metabolize the sugar lactose, producing both acid and gas as byproducts.

These chromogenic compounds are modified to change color or fluorescence by the addition of either enzymes or specific bacterial metabolites.

ELISA antibody technology has been developed to allow for readable detection by the naked eye for rapid identification of coliform microcolonies.

The raw sample is mixed with the beads, then a specific magnet is used to hold the target organisms against the vial wall and the non-bound material is poured off.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) are gene sequence-based methods currently being used to detect specific strains of indicator bacteria.

[5] Early studies showed that individuals who swam in waters with geometric mean coliform densities above 2300/100 mL for three days had higher illness rates.

In 1986, EPA revised its bacteriological ambient water quality criteria recommendations to include E. coli and enterococci.

[8] Most cases of bacterial gastroenteritis are caused by food-borne enteric microorganisms, such as Salmonella and Campylobacter; however, it is also important to understand the risk of exposure to pathogens via recreational waters.

This is especially the case in watersheds where human or animal wastes are discharged to streams and downstream waters are used for swimming or other recreational activities.

The results indicated that swimmers were more likely to have gastrointestinal symptoms, eye infections, skin complaints, ear, nose, and throat infections and respiratory illness than non-swimmers and in some cases, higher coliform levels correlated to higher incidence of gastrointestinal illness, although the sample sizes in these studies were small.

In general, children, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals require a lower dose of a pathogenic organism in order to contract an infection.

Respondents are asked to report the frequency and timing and location of exposures, detailed information about the amount of water swallowed and head submersion, and basic demographic characteristics such as age, gender, socioeconomic status and family composition.

Also, such an approach often ignores the complicated fate and transport processes that determine bacteria concentrations from the source to the point of exposure.

Also, many states have beach monitoring programs to warn swimmers when high levels of indicator bacteria are detected.