Electronic music

[15] The instruments offered expansions in pitch resources[17] that were exploited by advocates of microtonal music such as Charles Ives, Dimitrios Levidis, Olivier Messiaen and Edgard Varèse.

[49] The Music for Magnetic Tape Project was formed by members of the New York School (John Cage, Earle Brown, Christian Wolff, David Tudor, and Morton Feldman),[50] and lasted three years until 1954.

Cage wrote of this collaboration: "In this social darkness, therefore, the work of Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, and Christian Wolff continues to present a brilliant light, for the reason that at the several points of notation, performance, and audition, action is provocative.

Oliver Daniel telephoned and invited the pair to "produce a group of short compositions for the October concert sponsored by the American Composers Alliance and Broadcast Music, Inc., under the direction of Leopold Stokowski at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

After several concerts caused a sensation in New York City, Ussachevsky and Luening were invited onto a live broadcast of NBC's Today Show to do an interview demonstration—the first televised electroacoustic performance.

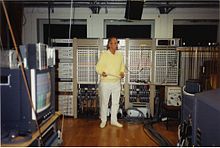

[79] Prominent composers such as Vladimir Ussachevsky, Otto Luening, Milton Babbitt, Charles Wuorinen, Halim El-Dabh, Bülent Arel and Mario Davidovsky used the RCA Synthesizer extensively in various compositions.

Schaeffer created a new collective, called Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM) and set about recruiting new members including Luc Ferrari, Beatriz Ferreyra, François-Bernard Mâche, Iannis Xenakis, Bernard Parmegiani, and Mireille Chamass-Kyrou.

Other composers of electronic music active in the UK included Ernest Berk (who established his first studio in 1955), Tristram Cary, Hugh Davies, Brian Dennis, George Newson, Daphne Oram and Peter Zinovieff.

[93] The intense activity occurring at CPEMC and elsewhere inspired the establishment of the San Francisco Tape Music Center in 1963 by Morton Subotnick, with additional members Pauline Oliveros, Ramon Sender, Anthony Martin, and Terry Riley.

[96] In an SFMOMA performance the following year (1964), the San Francisco Chronicle music critic Alfred Frankenstein commented, "the possibilities of the space-sound continuum have seldom been so extensively explored".

Examples include Varese's Poeme Electronique (tape music performed in the Philips Pavilion of the 1958 World Fair, Brussels) and Stan Schaff's Audium installation, currently active in San Francisco.

[102] In 1969 David Tudor brought a Moog modular synthesizer and Ampex tape machines to the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad with the support of the Sarabhai family, forming the foundation of India's first electronic music studio.

[133] King Tubby, for example, was a sound system proprietor and electronics technician, whose small front-room studio in the Waterhouse ghetto of western Kingston was a key site of dub music creation.

Instrumental prog rock was particularly significant in continental Europe, allowing bands like Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream, Cluster, Can, Neu!, and Faust to circumvent the language barrier.

Electronic music began to enter regularly in radio programming and top-sellers charts, as the French band Space with their debut studio album Magic Fly[156] or Jarre with Oxygène.

These developments led to the growth of synth-pop, which after it was adopted by the New Romantic movement, allowed synthesizers to dominate the pop and rock music of the early 1980s until the style began to fall from popularity in the mid-to-end of the decade.

Synth-pop was taken up across the world, with international hits for acts including Men Without Hats, Trans-X and Lime from Canada, Telex from Belgium, Peter Schilling, Sandra, Modern Talking, Propaganda and Alphaville from Germany, Yello from Switzerland and Azul y Negro from Spain.

Some synth-pop bands created futuristic visual styles of themselves to reinforce the idea of electronic sounds were linked primarily with technology, as Americans Devo and Spaniards Aviador Dro.

Keyboard synthesizers became so common that even heavy metal rock bands, a genre often regarded as the opposite in aesthetics, sound and lifestyle from that of electronic pop artists by fans of both sides, achieved worldwide success with themes as 1983 Jump[173] by Van Halen and 1986 The Final Countdown[174] by Europe, which feature synths prominently.

It was founded by Misha Mengelberg, Louis Andriessen, Peter Schat, Dick Raaymakers, Jan van Vlijmen [nl], Reinbert de Leeuw, and Konrad Boehmer.

Barry Vercoe describes one of his experiences with early computer sounds: At IRCAM in Paris in 1982, flutist Larry Beauregard had connected his flute to DiGiugno's 4X audio processor, enabling real-time pitch-following.

[179][180] In 1974, the WDR studio in Cologne acquired an EMS Synthi 100 synthesizer, which many composers used to produce notable electronic works—including Rolf Gehlhaar's Fünf deutsche Tänze (1975), Karlheinz Stockhausen's Sirius (1975–1976), and John McGuire's Pulse Music III (1978).

[182][183] Yamaha's engineers began adapting Chowning's algorithm for use in a digital synthesizer, adding improvements such as the "key scaling" method to avoid the introduction of distortion that normally occurred in analog systems during frequency modulation.

This standard was dubbed Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) and resulted from a collaboration between leading manufacturers, initially Sequential Circuits, Oberheim, Roland—and later, other participants that included Yamaha, Korg, and Kawai.

Common cheap popular sound chips of the first home computers of the 1980s include the SID of the Commodore 64 and General Instrument AY series and clones (like the Yamaha YM2149) used in the ZX Spectrum, Amstrad CPC, MSX compatibles and Atari ST models, among others.

Synth-pop continued into the late 1980s, with a format that moved closer to dance music, including the work of acts such as British duos Pet Shop Boys, Erasure and The Communards, achieving success along much of the 1990s.

Despite the industry's attempt to create a specific EDM brand, the initialism remains in use as an umbrella term for multiple genres, including dance-pop, house, techno, electro, and trance, as well as their respective subgenres.

[206] According to a 1997 Billboard article, "the union of the club community and independent labels" provided the experimental and trend-setting environment in which electronica acts developed and eventually reached the mainstream, citing American labels such as Astralwerks (the Chemical Brothers, Fatboy Slim, the Future Sound of London, Fluke), Moonshine (DJ Keoki), Sims, Daft Punk and City of Angels (the Crystal Method) for popularizing the latest version of electronic music.

[207] The first wave of indie electronic artists began in the 1990s with acts such as Stereolab (who used vintage gear) and Disco Inferno (who embraced modern sampling technology), and the genre expanded in the 2000s as home recording and software synthesizers came into common use.

[213] Such tools provide viable and cost-effective alternatives to typical hardware-based production studios, and thanks to advances in microprocessor technology, it is now possible to create high-quality music using little more than a single laptop computer.