Inga dams

[4] Despite the lack of progress during and in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the tantalizing possibilities offered by the Inga Falls remained prominent in engineers' minds.

The 1954 book Engineers' Dreams listed a host of massive projects that could theoretically be accomplished (among them the future Channel Tunnel), the largest being an Inga Dam that would create a lake stretching into the Sahara Desert.

[5] Before Congolese independence, the Belgians still harbored the hope of constructing a massive Inga development project to generate electricity for heavy industry.

[7] There was an important American connection to the project in the form of Clarence E. Blee, one of five foreigners on a 10-person study of the Inga site in 1957 and the chief engineer of the United States' foray into federal electrical and industrial development, the Tennessee Valley Authority.

An Inga scheme, loosely reported as consisting of a "series of power stations and dams", was finally passed by the Belgian Cabinet on 13 November 1957, and a group was slated to be created in order to study the possible uses of the project's electricity and the ways in which to fund it.

[8] A report from late April 1958 stated that excavation work would hopefully begin by midyear, with 1964/1965 as the year set to bring the initial stage to completion.

Industrial development would advance in step, helped by a start price of $0.002 per kwh, producing 500,000 tons of aluminum with the construction of the first plant and eventually aiming for a final production goal six times that.

[9] In February 1959 a group of prominent American investors including David Rockefeller visited the Inga Falls,[10] though construction was continually being pushed back from original estimates, then slated for 1961 or later.

Belgian authorities were still pushing the project while negotiating independence with Congolese delegates, with Minister Raymond Scheyven proposing a joint Congolese-Belgian company that would fund an Inga dam.

[13] PM Lumumba later backtracked and claimed that the deal was "only an agreement in principle",[14] but regardless he was deposed by Army Chief of Staff Mobutu Sese Seko less than two months later.

From the wreckage of the Belgian departure and the subsequent turmoil emerged Mobutu Sésé Seko, who seized full power for himself in November 1965 and would remain the Congo's authoritarian president until May 1997.

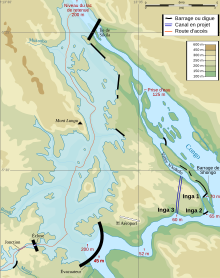

[16] In order to connect the power generating capacity at Inga with the copper and cobalt mines located near the Zambian border in Shaba Province (now Katanga), a new project aimed to build the longest high-voltage direct current power line in existence, bypassing local communities and converting into alternating current at its final destination.

A mix of private and public groups provided the financing, notably Citibank, Manufacturers Hanover Trust, and the U.S. Export-Import Bank, and it was the storied Boise, Idaho-based company, Morrison-Knudsen, that was contracted to do the work.

The DRC has faced the problem of rehabilitating the two existing dams, which have fallen into disrepair and operate far below original capacity at roughly 40%, or just over 700 MW combined.

[16] In May 2001 Siemens was reportedly negotiating with the government over a billion-dollar partnership that would involve restoration and modernization of the DRC's electrical grid, including the rehabilitation of the two existing Inga power plants,[23] though work was delayed.

Separately in May 2005 the Canadian company MagEnergy signed an agreement with SNEL to rehabilitate some of Inga II's turbines, with a completion goal of 2009.

[28] However, there is doubt over whether the government accepts the validity of the contract, and in the meantime the Canadian company First Quantum was hired to rehabilitate two separate Inga II turbines.

Inga III is the centerpiece of the Westcor partnership which envisions the interconnection of the electric grids of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Namibia, Angola, Botswana, and South Africa.

[31] For South Africa's public utility Eskom, Inga fit into a broader plan to turn an interconnected African grid into an electricity-exporting powerhouse, eventually supplying Europe and the Middle East.

[40] In October 2018, the government of the DRC announced the signing of contracts with a Sino-Spanish consortium to launch design studies for the construction of the Inga III dam with 11,000 MW and a total cost of $14 billion.

[43] The Grand Inga Dam, if harnessing much of the power of the river, could generate up to 39,000 MW – and would significantly boost the energy available to the African continent at a cost of more than $80 billion.

A study from Oxford University supports this cautious approach by showing that the average cost overrun for 245 large dams in 65 countries across six continents is 96% in real terms.

[44] The New Partnership for Africa's Development, with significant involvement of South African electric power company ESKOM, suggested in 2003 to start the Grand Inga project in 2010.

[49][50] However, in July 2016 the World Bank withdrew its funding following disagreements over the project despite power purchase agreements from South Africa and mining companies.

[56][57] Three international consortia are bidding for the contract to build the dam, known as Inga III, and to sell the power it generates, estimated at 4,800 MW.

This is nearly three times the power produced from Inga's two existing dams, which are decades old and have been crippled by neglect because of government debt and risk-averse investors.

The remaining 1000 megawatts would go to the national utility SNEL, helping provide power to an estimated 7 million people around Kinshasa, Congo's capital, and covering all the projected unmet electricity needs there by 2025.