Inhomogeneous cosmology

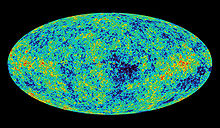

While the concordance model acknowledges this fact, it assumes that such inhomogeneities are not sufficient to affect large-scale averages of gravity observations.

[6][7] For example, in 2007, David Wiltshire proposed a model (timescape cosmology) in which backreactions caused time to run more slowly or, in voids, more quickly, thus leading supernovae observed in 1998 to be thought to be further away than they were.

[3] The conflict between the two cosmologies derives from the inflexibility of Einstein's theory of general relativity, which shows how gravity is formed by the interaction of matter, space, and time.

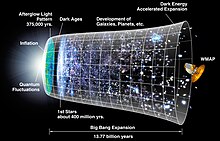

Therefore, in order to make his equations consistent with the apparently static universe, he added a cosmological constant, a term representing some unexplained extra energy.

But when in the late 1920s Georges Lemaître's and Edwin Hubble's observations proved Alexander Friedmann's notion (derived from general relativity) that the universe was expanding, the cosmological constant became unnecessary, Einstein calling it "my greatest blunder.

[10] Another observation in 1998 seemed to complicate the situation further: two separate studies[4][5] found distant supernovae to be fainter than expected in a steadily expanding universe; that is, they were not merely moving away from the earth but accelerating.

It also gave Einstein's cosmological constant new meaning, for by reintroducing it into the equation to represent dark energy, a flat universe expanding ever faster can be reproduced.

Most cosmologists still accept the concordance model, although science journalist Anil Ananthaswamy calls this agreement a "wobbly orthodoxy.

In inhomogeneous cosmology, the large-scale structure of the universe is modeled by exact solutions of the Einstein field equations (i.e. non-perturbatively), unlike cosmological perturbation theory, which is study of the universe that takes structure formation (galaxies, galaxy clusters, the cosmic web) into account but in a perturbative way.

[12] Inhomogeneous cosmology usually includes the study of structure in the Universe by means of exact solutions of Einstein's field equations (i.e. metrics)[12] or by spatial or spacetime averaging methods.

[13] Such models are not homogeneous,[14] but may allow effects which can be interpreted as dark energy, or can lead to cosmological structures such as voids or galaxy clusters.

[15] As of 2016[update], Thomas Buchert, George Ellis, Edward Kolb, and their colleagues[16] judged that if the universe is described by cosmic variables in a backreaction scheme that includes coarse-graining and averaging, then whether dark energy is an artifact of the traditional way of using the Einstein equation remains an unanswered question.

[8] This misidentification was the result of presuming an essentially homogeneous universe, as the standard cosmological model does, and not accounting for temporal differences between matter-dense areas and voids.

[3] One more important step being left out of the standard model, Wiltshire claimed, was the fact that as proven by observation, gravity slows time.

Wiltshire claims that the 1998 supernovae observations that led to the conclusion of an expanding universe and dark energy can instead be explained by Buchert's equations if certain strange aspects of general relativity are taken into account.

By employing a model-independent statistical approach, the researchers found that the Timescape model could account for the observed cosmic acceleration without the need for dark energy.