Inostrancevia

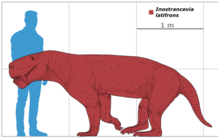

Possessing a skull measuring approximately 40 to 60 cm (16 to 24 in) long depending on the species, all for a body length reaching 3 to 3.5 m (9.8 to 11.5 ft), Inostrancevia is the largest known gorgonopsian, being rivaled in size only by the imposing Rubidgea.

The first classifications placed Inostrancevia as close to African taxa before 1948, the year in which Friedrich von Huene erected a distinct family, Inostranceviidae.

Although this model was mainly followed in the scientific literature of the 20th and early 21st centuries, phylogenetic analysis published since 2018 consider it to belong to a group of derived Russian origin gorgonopsians, now classified alongside the genera Suchogorgon, Sauroctonus and Pravoslavlevia, this latter and Inostrancevia forming the subfamily Inostranceviinae.

[3] This type of fauna from this period, previously known only from South Africa and India, is considered as one of the greatest paleontological discoveries of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

[5][13] Although the taxon was not officially described posthumously until 1922,[3] the use of this name in scientific literature dates back to the beginning of the 20th century, notably in the works of Friedrich von Huene and Edwin Ray Lankester.

However, the article officially describing this animal focuses primarily on the stratigraphic significance of the findings and is only a brief introduction to the anatomy of the new fossil material, being the subject for future study.

[2] Earlier, in June 2007, a team of paleontologists discovered an isolated left premaxilla, cataloged as NMT RB380, in the Ruhuhu Basin, southern Tanzania.

In their broad revision of the classification of therapsids published in 1956, David Watson and Alfred Romer recognized without argumentation almost all of the taxa erected by Pravoslavlev as valid,[30] but their opinions were never followed in subsequent works.

[32] In 1940, the paleontologist Ivan Yefremov expressed doubts about this classification, and considered that the holotype specimen of I. parva should be viewed as a juvenile of the genus and not as a distinct species.

[9][13][2] Also in his article, he considers that I. proclivis is a junior synonym of I. alexandri, but remains open to the question of the existence of this species, arguing his opinion with the insufficient preservation of type specimens.

[23] In 2003, Mikhail F. Ivakhnenko erected a new genus of Russian gorgonopsian under the name of Leogorgon klimovensis, on the basis of a partial braincase and a large referred canine, both discovered in the Klimovo-1 locality, in the Vologda Oblast.

[3] However, I. latifrons, although known from more fragmentary fossils, is estimated to have a more imposing size, the skull being 60 cm (24 in) long, indicating that it would have measured 3.5 m (11 ft) and weighed 300 kg (660 lb).

[9] I. africana is characterized by the strong constriction of the jugal under the orbit, a proportionally longer snout, the pineal foramen located in a deep parietal depression, as well as a much more raised and massive dentary bone.

[38] Although the postcranial anatomy of Inostrancevia was first described in detail in 1927 by Pravoslavlev,[53] new discoveries and anatomical descriptions of this taxon have led authors suggesting further revisions to broaden the skeletal understanding of the animal.

The scapula of this latter is unmistakable, with an enlarged plate-like blade unlike that of any other known gorgonopsians, but its anatomy is also unusual, with ridges and thickened tibiae, especially at their joint margins.

[12] From its original description published in 1922, Inostrancevia was immediately classified in the family Gorgonopsidae after anatomical comparisons made with the type genus Gorgonops.

[56] In 1989, Denise Sigogneau-Russell proposes a similar classification, but moves the taxon reuniting the two genera as a subfamily, being renamed Inostranceviinae, and is classified in the more general family Gorgonopsidae.

[54] In 2002, in his revision of the Russian gorgonopsians, Mikhail F. Ivakhnenko re-erects the family Inostranceviidae and classifies the taxon as one of the lineages of the superfamily "Rubidgeoidea", placed alongside the Rubidgeidae and Phtinosuchidae.

Based on observations made on the occipital bones and canines, Gebauer moved Inostrancevia as a sister taxon to the Rubidgeinae, a lineage consisting of robust African gorgonopsians.

[39] In 2018, in their description of Nochnitsa and re-description of the skull of Viatkogorgon, Kammerer and Vladimir Masyutin propose that all Russian and African taxa should be separately grouped into two distinct clades.

[13][50][59][2] The following cladogram shows the position of Inostrancevia within the Gorgonopsia after Kammerer and Rubidge (2022):[59] Nochnitsa Viatkogorgon Suchogorgon Sauroctonus Pravoslavlevia Inostrancevia Phorcys Eriphostoma Gorgonops Cynariops Lycaenops Smilesaurus Arctops Arctognathus Rubidgeinae Gorgonopsians are a major group of carnivorous therapsids, the oldest known definitive specimen coming from the Mediterranean island of Majorca, and which probably dates to the early Middle Permian, or even earlier.

[60] During the Middle Permian, the majority of representatives of this clade were quite small and their ecosystems were mainly dominated by dinocephalians, large therapsids characterized by strong bone robustness.

[64] After the Capitanian extinction, gorgonopsians began to occupy ecological niches abandoned by dinocephalians and large therocephalians, and adopted an increasingly imposing size, which very quickly gave them the role of superpredators.

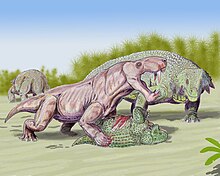

The study also indicated that the jaw of Inostrancevia was capable of a massive gape, perhaps enabling it to deliver a lethal bite, and in a fashion similar to the hypothesised killing technique of Smilodon (or 'saber-toothed cat').

[67] Antón provided an overview of gorgonopsian biology in is 2013 book, writing that despite their differences from saber-toothed mammals, many features of their skeletons indicated they were not sluggish reptiles but active predators.

While their brains were relatively smaller than those of mammals, and their sideways placed eyes provided limited stereoscopic vision, they had well-developed turbinals in their nasal cavity, a feature associated with an advanced sense of smell, which would have helped them track prey and carrion.

[68] Antón envisioned gorgonopsians would hunt by leaving their cover when prey was close enough, and use their relatively greater speed to pounce quickly on it, grab it with their forelimbs, and bite any part of the body that would fit in their jaws.

[69] Inostrancevia is currently the only formally recognized gorgonopsian genus that had a transcontinental distribution, being present in both territories from which the group's fossils are unanimously recorded, namely in Southern Africa and European Russia.

[70] The Salarevo Formation in particular (a horizon where the Russian species Inostrancevia hails from) was deposited in a seasonal, semi-arid-to-arid area with multiple shallow water lakes which was periodically flooded.

[66][72][65] Gorgonopsians, including Inostrancevia, disappeared in the Late Lopingian during the Permian–Triassic extinction event, mainly due to volcanic activities that originated in the Siberian Traps.