Interchangeable parts

Additional innovations included jigs for guiding the machine tools, fixtures for holding the workpiece in the proper position, and blocks and gauges to check the accuracy of the finished parts.

Blanc demonstrated in front of a committee of scientists that his muskets could be fitted with flintlock mechanisms picked at random from a pile of parts.

[1][page needed] In 1785 muskets with interchangeable locks caught the attention of the United States' Ambassador to France, Thomas Jefferson, through the efforts of Honoré Blanc.

Jefferson tried unsuccessfully to persuade Blanc to move to America, then wrote to the American Secretary of War with the idea, and when he returned to the USA he worked to fund its development.

President George Washington approved of the concept, and in 1798 Eli Whitney signed a contract to mass-produce 12,000 muskets built under the new system.

[6][need quotation to verify][7] Between 4th July 1793 and 25th November 1795, the London gunsmith Henry Nock delivered 12,010 'screwless' or 'Duke's' locks to the British Board of Ordnance.

[1][page needed] In the US, Eli Whitney saw the potential benefit of developing "interchangeable parts" for the firearms of the United States military.

Mass production using interchangeable parts was first achieved in 1803 by Marc Isambard Brunel in cooperation with Henry Maudslay and Simon Goodrich, under the management of (and with contributions by) Brigadier-General Sir Samuel Bentham,[10] the Inspector General of Naval Works at Portsmouth Block Mills, Portsmouth Dockyard, Hampshire, England.

At the time, the Napoleonic War was at its height, and the Royal Navy was in a state of expansion that required 100,000 pulley blocks to be manufactured a year.

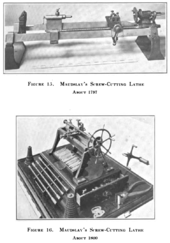

Marc Brunel, a pioneering engineer, and Maudslay, a founding father of machine tool technology who had developed the first industrially practical screw-cutting lathe in 1800 which standardized screw thread sizes for the first time,[11] collaborated on plans to manufacture block-making machinery; the proposal was submitted to the Admiralty who agreed to commission his services.

By 1805, the dockyard had been fully updated with the revolutionary, purpose-built machinery at a time when products were still built individually with different components.

Richard Beamish, assistant to Brunel's son and engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, wrote: So that ten men, by the aid of this machinery, can accomplish with uniformity, celerity and ease, what formerly required the uncertain labour of one hundred and ten.By 1808, annual production had reached 130,000 blocks and some of the equipment was still in operation as late as the mid-twentieth century.

[18] During this contract, Terry crafted four-thousand wooden gear tall case movements, at a time when the annual average was about a dozen.

[22][23] Muir demonstrates the close personal ties and professional alliances between Simeon North and neighbouring mechanics mass-producing wooden clocks to argue that the process for manufacturing guns with interchangeable parts was most probably devised by North in emulation of the successful methods used in mass-producing clocks.

[1][page needed] During these decades, true interchangeability grew from a scarce and difficult achievement into an everyday capability throughout the manufacturing industries.

As recently as the 1960s, when Alfred P. Sloan published his famous memoir and management treatise, My Years with General Motors, even the long-time president and chair of the largest manufacturing enterprise that had ever existed knew very little about the history of the development, other than to say that: [Henry M. Leland was], I believe, one of those mainly responsible for bringing the technique of interchangeable parts into automobile manufacturing.

[26]One of the better-known books on the subject, which was first published in 1984 and has enjoyed a readership beyond academia, has been David A. Hounshell's From the American System to Mass Production, 1800–1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States.