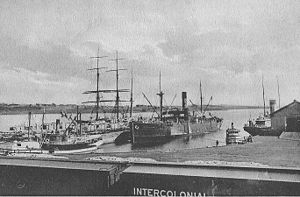

Intercolonial Railway

Construction in the 1850s saw two important rail lines opened in the Maritimes to connect cities on the Atlantic coast with steamship routes in the Northumberland Strait and the Gulf of St. Lawrence: An intercolonial rail system in the British North American colonies was never far from the minds of government and civic leaders and in an 1851 speech at a Mason's Hall in Halifax, local editor of the Novascotian, Joseph Howe spoke these words: I am neither a prophet, nor the son of a prophet, yet I will venture to predict that in five years we shall make the journey hence to Quebec and Montreal, and home through Portland and St. John, by rail; and I believe that many in this room will live to hear the whistle of the steam engine in the passes of the Rocky Mountains, and to make the journey from Halifax to the Pacific in five or six days.

An 1862 conference in Quebec City led to an agreement on financing the railway with the Maritime colonies and Canada splitting construction costs and Britain assuming any debts, but the deal fell through within months.

[citation needed] It is speculated that this failure to achieve a deal on the Intercolonial in 1862, combined with the ongoing concerns over the American Civil War, led to the Charlottetown Conference in 1864, and eventually to Confederation of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the Province of Canada (Ontario and Quebec) in 1867.

The route connecting the NSR and the E&NA was not contestable as the line had to cross the Cobequid Mountains and the Isthmus of Chignecto where options were limited by the local topography.

A commission of engineers, headed by Sandford Fleming had been unanimously appointed in 1863 to consider the following: Despite pressure from commercial interests in the Maritimes and New England who wanted a rail connection closer to the border, the Chaleur Bay routing was chosen, amid the backdrop of the American Civil War, as it would keep the Intercolonial far from the boundary with Maine.

This latter decision proved extremely far-sighted as the strength of the bridges and their material saved the line from lengthy closures on numerous occasions in the early years during forest fire seasons.

[11] In the late 1880s, the ICR received running rights over the GTR main line between Levis and Montreal (via Richmond), allowing passengers and cargo from the Maritimes to Canada's then-largest city to transit without interchanging.

The Temiscouata Railway was completed in 1889 from Rivière du Loup to Edmundston, New Brunswick, giving the ICR a connection with the Canadian Pacific line up the St. John Valley.

[12] In 1890, the ICR completed construction of what had begun as the Cape Breton Eastern Extension Railway, with a line running from its former NSR terminus at New Glasgow eastward through Antigonish to the port of Mulgrave where a railcar ferry service was instituted over a 1.6-kilometre (1 mi) route across the deep waters of the Strait of Canso to Point Tupper.

In 1904 the ferry Champlain entered service between Pointe St. Denis and the North Shore ports of St. Irenée, Murray Bay and Cap à l'Aigle.

As a result of the ICR with its subsidized freight-rate agreements, as well as the National Policy of prime minister John A. Macdonald, the industrial revolution struck Maritime towns quickly.

Many ICR employees, most notably train dispatcher Vincent Coleman, responded with heroism and desperate determination to evacuate wounded and summon relief.

The railway mobilized repair crews from across Eastern Canada to clear debris with remarkable speed and resumed its full schedule five days after the explosion, albeit with diminished passengers cars as many were severely damaged.

The ICR was a pervasive and ubiquitous presence in the Maritimes, with the company employing thousands of workers, purchasing millions of dollars in services, coal, and other local products annually, operating ferries to Cape Breton Island at the Strait of Canso, and carrying the Royal Mail.

The IRC was the face of the federal government in many communities in a region that was still somewhat hostile to what many believed was a forced Confederation (anti-Confederation organizers remained active in Nova Scotia and particularly New Brunswick into the 1880s).

On December 20, 1918, Reid consolidated the management of the various companies by creating the Canadian National Railways (CNR), by means of an order issued by the Privy Council.

This was largely because ICR balance books never had to contend with falling freight and passenger revenues as a result of post-Second World War highway construction and airline usage.

Following its demise in 1918, the ICR trackage and facilities formed the majority of CNR's Maritimes operations and CN (acronym abbreviated post-1960) maintained Moncton as its principal regional headquarters well into the 1980s.

Until the late-1970s, the ICR line through northern New Brunswick and eastern Quebec continued to host a large portion of CN's freight and the majority of its passenger traffic to Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland.

A short section on the waterfront of Lévis was abandoned on October 24, 1998, due to network rationalization, resulting in the CN main line between Charny and the east end of Levis running on former NTR trackage.