International Committee of the Red Cross archives

[1] Along with the ICRC Library, the archives are widely considered to be the greatest repository for records on International humanitarian law (IHL).

The ICRC – or rather its predecessor – was founded in February 1863 at the "Ancient Casino" in the Rue de L'Evêche 3 of Geneva's Old Town by five men: businessman-turned-activist Henry Dunant, who had laid out the basic ideas in his much-acclaimed book A Memory of Solferino; lawyer and philanthropist Gustave Moynier; the medical doctors Louis Appia and Théodor Maunoir; and the General Guillaume Henri Dufour.

[5] At the same moment, its archives came into being:[3]"Dunant, as secretary, signed off the minutes of the first meeting of the International Committee for Relief to the Wounded, the precursor of the ICRC.

"[1]The actual address of the newly founded Red Cross - and thus probably of its fledgling archives – became Dunant's private residence, the third floor of his family's "Maison Diodati" in the Old Town at Rue du Puits-Saint-Pierre 4.

[5] However, as Dunant's colonial businesses in Algeria collapsed, he declared bankruptcy in 1867 and was pushed out of the ICRC by its president Moynier in the following year.

It may be assumed that Dunant's ICRC-related records were transferred to Moynier's splendid city residence in Rue de l'Athénée No.

[8] Subsequently, the ICRC archives took over the archival holdings of the Basel Agency with some twelve linear meters of records about prisoners of wars (PoW) from the latter war and of the Trieste Agency with one linear meter of files[2] on PoW from the Great Eastern Crisis in the Balkans between the Russian and Ottoman Empires and their respective allies (1875–1878).

[2] Shortly after the beginning of the First World War in 1914, the ICRC under its president Gustave Ador decided to establish the International Prisoners-of-War Agency (IPWA).

It soon became commonly associated with the ICRC and significantly contributed to its positive image, thus also to its first Nobel Peace Prize in 1917 (The ousted Dunant had received the first one in 1901 as an individual).

[12] His friend, the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig, provided a lively description of the commitment:"A rough stool, a small table of unpolished deal, the turmoil of typewriters, the bustle of human beings questioning, calling one to another, hastening to and fro – such was Romain Rolland's battlefield in this campaign against the afflictions of the war.

Here, while other authors and intellectuals were doing their utmost to foster mutual hatred, he endeavored to promote reconciliation, to alleviate the torment of a fraction among the countless sufferers by such consolation as the circumstances rendered possible.

He neither desired, nor occupied a leading position in the work of the Red Cross; but, like so many other nameless assistants, he devoted himself to the daily task of promoting the interchange of news.

"[9]Étienne Clouzot (1881–1944) – an archivist palaeographer, who was also a columnist for the liberal daily newspaper Journal de Genève (which had published an anonymous essay by Dunant about Solferino and thus played a role in the founding of the ICRC, illustrating the networking connections of Geneva's patrician family dynasties) – became the director of one of the Entente sections and designed the classification system for the millions of index cards.

"[2]The IPWA stopped operating in 1924, but the ICRC archives kept on collecting information from various armed conflicts which in many cases may be considered a continuation of WWI.

It had been built in 1848 for the Banker Barthélemy Paccard and was then owned by his son-in-law Gustave Moynier (1826–1910), who was the first president of the ICRC and stayed in that office for a record-term of 47 years until his death.

Once again, Étienne Clouzot played a prominent role: "in 1939, fuelled by his experience in the International Prisoners of War Agency, he helped organize the Central Prisoners of War Agency, becoming a member of its Technical Directorate"[6]Another key person became Suzanne Ferrière, who had assisted her uncle Frédéric at the IPWA during WWI and now instituted a new family messaging system.

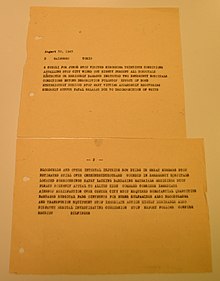

One of the last – and most important – documents from the WWII period was issued on 29 August 1945, only days before the end of the war, by Fritz Bilfinger, an ICRC delegate who reached the apocalyptic ruins of Hiroshima just some three weeks after the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) dropped the atomic bomb "Little Boy" on the Japanese city.

It was 110 years after its inception that the ICRC Assembly as the governing body of the organisation formalised this case-by-case practise as a first step of opening up:"The system of ad hoc derogations allowing access to select archival materials was however denounced by researchers as being incoherent, partial and subjective.

Furthermore, by the late 1970s and 1980s, the social mood began channelling growing criticism towards the ICRC's perceived role and stance during the Second World War, specifically regarding the Nazi genocide and concentration camps.

If prior to this the ICRC had managed its image by mostly keeping its archives out of the public arena, it seemed that maintaining its reputation depended on bringing them to the fore, albeit with due respect for confidentiality.

[19] It took almost another six years – until January 1996 – that the ICRC Assembly officially adopted the right of the general public for access to the archives[17] and defined a policy of transparency.

[8] The first researcher to enjoy the opening was the British human rights journalist Caroline Moorehead, who was writing an official chronicle of the ICRC history: Dunant's Dream.

[1] Subsequently, tailormade automation processes, including more recently the use of artificial intelligence (ai), have been explored to adequately preserve the institutional memory.