International response to the Holocaust

[citation needed] Before, during and after the war, the British government limited Jewish immigration to Mandatory Palestine so as to avoid a negative reaction from Palestinian Arabs.

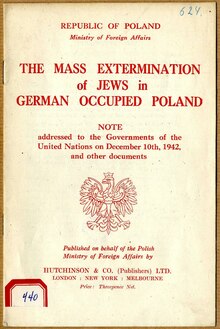

[5] The British government, along with all UN member nations, received credible evidence about the Nazi attempts to exterminate the European Jewry as early as 1942 from the Polish government-in-exile.

[6] Additionally the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden met with Jan Karski, courier to the Polish resistance who, having been smuggled into the Warsaw ghetto by the Jewish underground, as well as having posed as an Estonian guard at Bełżec transit camp, provided him with detailed eyewitness accounts of Nazi atrocities against the Jews.

[7][8] These lobbying efforts triggered the Joint Declaration by Members of the United Nations of 17 December 1942 which made public and condemned the mass extermination of the Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland.

The statement was read to British House of Commons in a floor speech by Foreign secretary Anthony Eden, and published on the front page of the New York Times and many other newspapers.

[16] However as early as August 1941, Radio Moscow's Yiddish language broadcasts publicised that the Germans were systemically massacring Jews in the occupied areas of the Soviet Union.

From 1941 on, the Polish government-in-exile in London played an essential part in revealing Nazi crimes[20] providing the Allies with some of the earliest and most accurate accounts of the ongoing Holocaust of European Jews.

[23][24] Though its representatives, like the Foreign Minister Count Edward Raczyński and the courier of the Polish Underground movement, Jan Karski, called for action to stop it, they were unsuccessful.

Most notably, Jan Karski met with British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden as well as US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, providing the earliest eyewitness accounts of the Holocaust.

The statement was read to British House of Commons in a floor speech by Foreign secretary Anthony Eden, and published on the front page of the New York Times and many other newspapers.

Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the country's consul at Bordeaux, nonetheless issued large numbers of visas to refugees, including Jews, fleeing the German advance but was later officially sanctioned for his actions.

The historian Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses writes that it was nonetheless considered insignificant: Salazar's analysis of the European situation [...] was based on an old-fashioned brand of realpolitik which saw states and their leaders acting out of reasonable and quantifiable considerations.

After lobbying from Moisés Bensabat Amzalak, a Jewish regime loyalist, Salazar also unsuccessfully attempted to intercede with the German government on behalf of the Portuguese Sephardic community in the German-occupied Netherlands.

While, on the one hand, the Spanish regime, as always inconsistently, issued instructions to its representatives to try to prevent the deportation of Jews, on the other, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Madrid allowed the Nazis and Vichy puppet government to apply anti-Jewish regulations to people whom Spain should have protected".

After he was ordered to withdraw from the country ahead of the Red Army's advance, he encouraged Giorgio Perlasca, an Italian businessman, to pose as the Spanish consul-general and continue his activities.

[42] Stanley G. Payne described Sanz Briz's actions as "a notable humanitarian achievement by far the most outstanding of anyone in Spanish government during World War II" but argued that he "might have accomplished even more had he received greater assistance from Madrid".

[46] Even so, the historian Paul A. Levine writes that "Swedish officials, and in fact much of the newspaper-reading public, had as much or more information about many details of the 'Final Solution' than their counterparts in other neutral or Allied countries".

In the post-war period, the Swedish government placed emphasis on its humanitarian actions to save Jews as a means of deflecting criticism of its economic and political relations with Nazi Germany.

Historian Ingrid Lomfors states that this "sowed the seed of the image of Sweden as a 'humanitarian superpower'" in post-war Europe and its prominent involvement in the United Nations.

[53] In 1942 the President of the Swiss Confederation, Philipp Etter as a member of the Geneva-based ICRC even persuaded the committee not to issue a condemnatory proclamation concerning German "attacks" against "certain categories of nationalities".

Some such as Luis Martins de Souza Dantas, Brazil's ambassador in Vichy France, nonetheless actively disobeyed their instructions and continued to issue visas to Jews as late as 1941.

Gonzalo Montt Rivas, Chilean consul in Prague, reported to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that "German triumph [in the war] will leave Europe freed of Semites" in November 1941.

According to the historian Richard Breitman, his reports "reveal considerable access to the thinking of Nazi officials" which he speculates may have originated from Montt's friendly relations with the Foreign Intelligence Service of the Reich Security Main Office.

Chilean diplomatic correspondence, including Montt's November dispatch, was regularly intercepted by British intelligence services and shared with their American counterparts.

[65] The pontificate of Pius XII coincided with the Second World War and the Nazi Holocaust, which saw the industrialized mass murder of millions of Jews and others by Adolf Hitler's Germany.

At Christmas 1942, once evidence of the industrial slaughter of the Jews had emerged, he voiced concern at the murder of "hundreds of thousands" of "faultless" people because of their "nationality or race".

When 60,000 German soldiers and the Gestapo occupied Rome in 1943, thousands of Jews were hiding in churches, convents, rectories, the Vatican and the papal summer residence.

According to Joseph Lichten, the Vatican was called upon by the Jewish Community Council in Rome to help fill a Nazi demand of one hundred pounds of gold.

The International Committee of the Red Cross did relatively little to save Jews during the Holocaust and discounted reports of the organized Nazi genocide, such as of the murder of Polish Jewish prisoners that took place at Lublin.

[72] The UK and the US met in Bermuda in April 1943 to discuss the issue of Jewish refugees who had been liberated by Allied forces and the Jews who remained in Nazi-occupied Europe.