Operation Demetrius

After the August 1969 riots, the British Army was deployed on the streets to bolster the police, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC).

Most loyalist attacks were directed against Catholic civilians, but they also clashed with state forces and the IRA on a number of occasions.

[7] The idea of re-introducing internment for Irish republican militants came from the Unionist government of Northern Ireland, headed by Prime Minister Brian Faulkner.

It was agreed to re-introduce internment at a meeting between Faulkner and British Prime Minister Edward Heath on 5 August 1971.

However, Faulkner argued that a ban on parades was unworkable, that the rifle clubs posed no security risk, and that there was no evidence of loyalist terrorism.

The list also included leaders of the non-violent Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association and People's Democracy such as Ivan Barr and Michael Farrell.

Specially trained personnel were sent to Northern Ireland to familiarize the local forces in what became known as the 'five techniques', methods of interrogation described by opponents as "a euphemism for torture".

In an internal memorandum dated 22 December 1971, one Brigadier Lewis reported to his superiors in London on the state of intelligence-gathering in Northern Ireland, saying that he was "very concerned about lack of interrogation in depth" by the RUC and that "some Special Branch out-station heads are not attempting to screw down arrested men and extract intelligence from them".

[15] The Detention of Terrorists Order of 7 November 1972, made under the authority of the Temporary Provisions Act, was used after direct rule was instituted.

Internees arrested without trial pursuant to Operation Demetrius could not complain to the European Commission of Human Rights about breaches of Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) because on 27 June 1957, the UK lodged a notice with the Council of Europe declaring that there was a "public emergency within the meaning of Article 15(1) of the Convention".

[16] Operation Demetrius began on Monday 9 August at 4 am and progressed in two parts: In the first wave of raids across Northern Ireland, 342 people were arrested.

[25] Protestant and Catholic families fled "to either side of a dividing line, which would provide the foundation for the permanent peaceline later built in the area".

[25] By 13 August, media reports indicated that the violence had begun to wane, seemingly due to exhaustion on the part of the IRA and security forces.

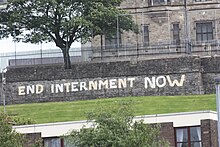

[26] On 15 August, the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) announced that it was starting a campaign of civil disobedience in response to the introduction of internment.

By 17 October, it was estimated that about 16,000 households were withholding rent and rates for council houses as part of the campaign of civil disobedience.

[27] Following the suspension of the Northern Ireland Government, internment was continued with some changes by the direct rule administration until 5 December 1975.

[1] Historians generally view the period of internment as inflaming sectarian tensions in Northern Ireland, while failing in its goal of arresting key members of the IRA.

Senator Maurice Hayes, Catholic Chairman of the Northern Ireland Community Relations Commission at the time, has described internment as "possibly the worst of all the stupid things that government could do".

The list's lack of reliability and the arrests that followed, complemented by reports of internees being abused,[10] led to more nationalists identifying with the IRA and losing hope in non-violent methods.

These allegedly included waterboarding,[34] electric shocks, burning with matches and candles, forcing internees to stand over hot electric fires while beating them, beating and squeezing of the genitals, inserting objects into the anus, injections, whipping the soles of the feet, and psychological abuse such as Russian roulette.

Domestic Law ... (c) We have received both written and oral representations from many legal bodies and individual lawyers from both England and Northern Ireland.

[37]As foreshadowed in the Prime Minister's statement, directives expressly forbidding the use of the techniques, whether alone or together, were then issued to the security forces by the government.

British Prime Minister Ted Heath's reaction was a dismissive telegram telling Lynch to mind his own business.

[42] The implications are (a) that the Irish government recognised the value of the intelligence which the British were acquiring (albeit illegally), and (b) that Dublin had a stake in impeding Britain's attempt to overcome the IRA by military means, at least until the British had implemented radical constitutional reforms opening up the path to Irish unification.

The Irish Government, on behalf of the men who had been subject to the five techniques, took a case to the European Commission on Human Rights (Ireland v. United Kingdom, 1976 Y.B.

The Commission stated that it unanimously considered the combined use of the five methods to amount to torture, on the grounds that (1) the intensity of the stress caused by techniques creating sensory deprivation "directly affects the personality physically and mentally"; and (2) "the systematic application of the techniques for the purpose of inducing a person to give information shows a clear resemblance to those methods of systematic torture which have been known over the ages ... a modern system of torture falling into the same category as those systems applied in previous times as a means of obtaining information and confessions.

Although the five techniques, as applied in combination, undoubtedly amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment, although their object was the extraction of confessions, the naming of others and/or information and although they were used systematically, they did not occasion suffering of the particular intensity and cruelty implied by the word torture as so understood.

They now give this unqualified undertaking, that the 'five techniques' will not in any circumstances be reintroduced as an aid to interrogation.In 2013, declassified documents revealed the existence of the interrogation centre at Ballykelly.

[4][47] Following the 2014 revelations, the President of Sinn Féin, Gerry Adams, called on the Irish government to bring the case back to the ECHR because the British government, he said, "lied to the European Court of Human Rights both on the severity of the methods used on the men, their long term physical and psychological consequences, on where these interrogations took place and who gave the political authority and clearance for it".

[48] On 2 December 2014, the Irish government announced that, having reviewed the new evidence and following requests from the survivors, it had decided to officially ask the ECHR to revise its 1978 judgement.