Population inversion

It is called an "inversion" because in many familiar and commonly encountered physical systems, this is not possible[non sequitur].

Since E2 − E1 ≫ kT, it follows that the argument of the exponential in the equation above is a large negative number, and as such N2/N1 is vanishingly small; i.e., there are almost no atoms in the excited state.

The rate of absorption is proportional to the radiation density of the light, and also to the number of atoms currently in the ground state, N1.

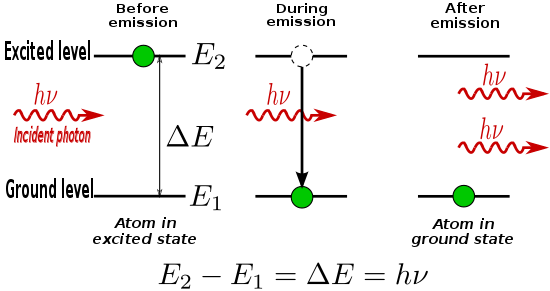

The energy difference between the two states ΔE21 is emitted from the atom as a photon of frequency ν21 as given by the frequency-energy relation above.

In this case, the excited atom relaxes to the ground state, and it produces a second photon of frequency ν21.

Specifically, an excited atom will act like a small electric dipole which will oscillate with the external field provided.

The rate at which stimulated emission occurs is proportional to the number of atoms N2 in the excited state, and the radiation density of the light.

The base probability of a photon causing stimulated emission in a single excited atom was shown by Albert Einstein to be exactly equal to the probability of a photon being absorbed by an atom in the ground state.

Some of these atoms decay via spontaneous emission, releasing incoherent light as photons of frequency, ν.

Recall from the descriptions of absorption and stimulated emission above that the rates of these two processes are proportional to the number of atoms in the ground and excited states, N1 and N2, respectively.

For instance, transitions are only allowed if ΔS = 0, S being the total spin angular momentum of the system.

In real materials, other effects, such as interactions with the crystal lattice, intervene to circumvent the formal rules by providing alternate mechanisms.

In contrast fluorescence in materials is characterized by emission which ceases when the external illumination is removed.

Transitions that do not involve the absorption or emission of radiation are not affected by selection rules.

The existence of intermediate states in materials is essential to the technique of optical pumping of lasers (see below).

A population inversion is required for laser operation, but cannot be achieved in the above theoretical group of atoms with two energy-levels when they are in thermal equilibrium.

In fact, any method by which the atoms are directly and continuously excited from the ground state to the excited state (such as optical absorption) will eventually reach equilibrium with the de-exciting processes of spontaneous and stimulated emission.

To achieve lasting non-equilibrium conditions, an indirect method of populating the excited state must be used.

This process is called pumping, and does not necessarily always directly involve light absorption; other methods of exciting the laser medium, such as electrical discharge or chemical reactions, may be used.

To have a medium suitable for laser operation, it is necessary that these excited atoms quickly decay to level 2.

The energy released in this transition may be emitted as a photon (spontaneous emission), however in practice the 3 → 2 transition called the Auger effect (labeled R in the diagram) is usually radiationless, with the energy being transferred to vibrational motion (heat) of the host material surrounding the atoms, without the generation of a photon.

As before, the presence of a fast, radiationless decay transition results in the population of the pump band being quickly depleted (N4 ≈ 0).

In a four-level system, any atom in the lower laser level E2 is also quickly de-excited, leading to a negligible population in that state (N2 ≈ 0).

In some media it is possible, by imposing an additional optical or microwave field, to use quantum coherence effects to reduce the likelihood of a ground-state to excited-state transition.

To create a population inversion under these conditions, it is necessary to selectively remove some atoms or molecules from the system based on differences in properties.