Irish Unionist Alliance

In 1919 the IUA finally split apart with the founding of the break-away Unionist Anti-Partition League, effectively signalling the death of institutional unionism in most of Ireland.

[2] The ILPU had been established to prevent electoral competition between Liberals and Conservatives in the three southern provinces on a common platform of maintenance of the union.

Prior to 1891, unionists had seen considerable electoral losses across southern Ireland at the hands of the pro-Home Rule Irish Parliamentary Party, founded a decade earlier.

[3] In the three counties of Ulster which would later become part of the Irish Free State, the unionists failed to come close to winning in Monaghan North, their strongest constituency of the eight in question, and never even contested West Donegal.

The strength of the northern unionist wing played a vital role in the shift of power in the pro-union movement to Conservative and Orange elements.

[8][9] This body sought to coordinate the IUA's election and lobbying activity, whilst recognising the distinct differences between the northern and southern parties.

[12] It was known that the passage of a Home Rule Bill for Ireland was becoming increasingly likely, and as a result many Southern Unionists began to seek a political compromise which would see their interests protected.

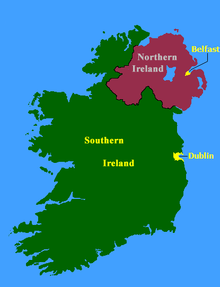

Many unionists in the south became strongly opposed to any plan to partition the island, as they knew that it would leave them isolated from the unionist-majority areas.

Several prominent Southern Unionists, such as Sir Horace Plunkett and Lord Monteagle, became convinced that a degree of home rule was going to be necessary if Ireland was to avoid partition and remain in the Union.

[16] Despite these internal difficulties, between September 1911 and July 1914 the Joint Committee of the Unionist Associations of Ireland continued its campaign across the British Isles.

[18] The Alliance's official opposition to partition led to it being marginalised in the 1918 general election, which showed the rising influence of the republican Sinn Féin party on the one hand and the strength of Ulster Unionist Council on the other.

The party split anyway, with Lord Midleton and senior southern leaders forming the break-away Unionist Anti-Partition League that same day.

The Irish Times, said to be the "voice of Southern Unionists", realised that the 1920 Act would not work and argued from late 1920 for "Dominion Home Rule", the compromise that was eventually agreed upon in the 1921–22 Anglo-Irish Treaty.

The IUA helped form the Southern Irish Loyalist Relief Association to assist war refugees and claim compensation for damage to property.

[27] Unionists continued to have a majority on Rathmines Council until 1929, when the IUA's successors lost their last elected representatives in the Irish Free State.

Many were members of the privileged Anglo-Irish class, who valued their cultural affiliations with the British Empire, and had close personal connections to the aristocracy in Britain.

[30] They were generally members of the Anglican Church of Ireland, although there were several notable Catholic unionists, such as The 5th Earl of Kenmare, and Sir Antony MacDonnell.

These included Jacob's Biscuits, Bewley's, Beamish and Crawford, Brown Thomas, Cantrell & Cochrane, Denny's Sausages,[35] Findlaters,[36] Jameson's Whiskey, W.P.

& R. Odlum, Cleeve's, R&H Hall, Dockrell's, Arnott's, Elverys, Goulding Chemicals, Smithwick's, The Irish Times and the Guinness brewery, then southern Ireland's largest company.

They were concerned that a new home rule state might create new taxes between them and their markets in Britain and the Empire, that would add to their costs and probably reduce sales and therefore employment.

As a group, Southern Unionist landowners were richer than their fellow Irishmen by about £90 million by 1914, which would either stay in the Irish economy, given a favourable political arrangement, or leave if the outcome appeared too uncertain or too radical.

Many Southern Unionists were members of the landed gentry, and these were prominent in horse breeding and racing, and as British Army officers.

[39] Lord Midleton described Southern Unionists as "lacking political insight and cohesion" and "restricting themselves to the easy task of attending meetings in Dublin".

Many Ulster Unionists were also drawn from the province's prosperous middle class, who had benefited greatly from heavy industrialisation in the region.

The Irish Unionist Alliance had no formal method of electing and deposing of its leadership, and leaders of the IUA were more informally 'acknowledged' by other prominent figures.

The party's first leader was Colonel Edward James Saunderson, a former Conservative Member of Parliament, who was most active in attempting to create an all-Ireland unionist movement.