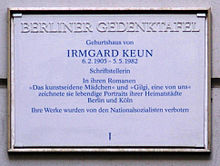

Irmgard Keun

Noted for her portrayals of the life of women, she is described as "often reduced to the bold sexuality of her writing, [yet] a significant author of the late Weimar period and die Neue Sachlichkeit.

Keun later recalled her mother as "stark hausfraulich eingestellt, auf eine sehr schauerliche Weise" (quite domestically inclined, in a very horrible way).

[7] Keun continued to publish in Germany after 1935, occasionally using pseudonyms, but after she was finally banned from publishing by the authorities - and after she had tried to sue the government for loss of income, and her final appeal to be admitted to the Reichsschrifttumskammer [de; fr] (the official author's association of Nazi Germany, a subdivision of the Reich Chamber of Culture) was refused - she went into exile to Belgium and later the Netherlands in 1936.

Keun claimed she seduced a Nazi official in the Netherlands and, however that may be, her cover back in Germany may have been helped by the fact that the British Daily Telegraph (among others) reported her suicide in Amsterdam on 16 August 1940.

Keun received great acclaim for her sharp-witted books, most notably from such well-known authors as Alfred Döblin and Kurt Tucholsky, who said about her, "A woman writer with humor, check this out!".

Breaking the archetypal mold, Keun's characters offer depth to the feminine identity and challenge the idea that a woman must be placed into a category.

For example, "Keun's representative novels of the New Woman's experience during the Weimar Republic, Gilgi—eine von uns (1931) and Das kunstseidene Mädchen (1932), feature two such young stylized New Women, Gilgi and Doris, who try to shape their lives in the aforementioned image by taking their cues from the popular media[10]".

In the case of Das kunstseidene Mädchen (The Artificial Silk Girl), Keun tells the story from Doris' perspective, which she does to give the reader "insights into the social injustice of Weimar Berlin's class and gender hierarchy[11]".

Keun's novel reflects critically on these discourses by casting its heroine's sentimental journey in terms of an education in vision.