Irreducible complexity

[2][5] Behe introduced the expression irreducible complexity along with a full account of his arguments in his 1996 book Darwin's Black Box, and he said it made evolution through natural selection of random mutations impossible, or extremely improbable.

The court found that "Professor Behe's claim for irreducible complexity has been refuted in peer-reviewed research papers and has been rejected by the scientific community at large.

[13] The idea that the interdependence between parts would have implications for the origins of living things was raised by writers starting with Pierre Gassendi in the mid-17th century[14] and by John Wilkins (1614–1672), who wrote (citing Galen), "Now to imagine, that all these things, according to their several kinds, could be brought into this regular frame and order, to which such an infinite number of Intentions are required, without the contrivance of some wise Agent, must needs be irrational in the highest degree.

In The Origin of Species (1859), he wrote, "If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down.

In the late 19th century, in a dispute between supporters of the adequacy of natural selection and those who held for inheritance of acquired characteristics, one of the arguments made repeatedly by Herbert Spencer, and followed by others, depended on what Spencer referred to as co-adaptation of co-operative parts, as in: "We come now to Professor Weismann's endeavour to disprove my second thesis—that it is impossible to explain by natural selection alone the co-adaptation of co-operative parts.

[28] The history of this concept in the dispute has been characterized: "An older and more religious tradition of idealist thinkers were committed to the explanation of complex adaptive contrivances by intelligent design.

... Another line of thinkers, unified by the recurrent publications of Herbert Spencer, also saw co-adaptation as a composed, irreducible whole, but sought to explain it by the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

"[29] St. George Jackson Mivart raised the objection to natural selection that "Complex and simultaneous co-ordinations ... until so far developed as to effect the requisite junctions, are useless".

[30] In the 2012 book Evolution and Belief, Confessions of a Religious Paleontologist, Robert J. Asher said this "amounts to the concept of 'irreducible complexity' as defined by ... Michael Behe".

In 1975 Thomas H. Frazzetta published a book-length study of a concept similar to irreducible complexity, explained by gradual, step-wise, non-teleological evolution.

After James Watson and Francis Crick published the structure of DNA in the early 1950s, General Systems Theory lost many of its adherents in the physical and biological sciences.

For example, in the July 1965 issue of Creation Research Society Quarterly Harold W. Clark argued that the complex interaction of yucca moths with the plants they fertilize would not function if it was incomplete, so could not have evolved; "The whole procedure points so strongly to intelligent design that it is difficult to escape the conclusion that the hand of a wise and beneficent creator has been involved.

[49] The second edition of Of Pandas and People, published in 1993, had extensive revisions to Chapter 6 Biochemical Similarities with new sections on the complex mechanism of blood clotting and on the origin of proteins.

"[51][52] On Access Research Network [3 February 1999] Behe posted "Molecular Machines: Experimental Support for the Design Inference" with a note that "This paper was originally presented in the Summer of 1994 at the meeting of the C. S. Lewis Society, Cambridge University."

It had worked perfectly as something other than a mousetrap.... my rowdy friend had pulled a couple of parts—probably the hold-down bar and catch—off the trap to make it easier to conceal and more effective as a catapult... [leaving] the base, the spring, and the hammer.

[61] Behe's original examples of irreducibly complex mechanisms included the bacterial flagellum of E. coli, the blood clotting cascade, cilia, and the adaptive immune system.

[62][63] The judge in the Dover trial wrote "By defining irreducible complexity in the way that he has, Professor Behe attempts to exclude the phenomenon of exaptation by definitional fiat, ignoring as he does so abundant evidence which refutes his argument.

Although Behe acknowledged that the evolution of the larger anatomical features of the eye have been well-explained, he pointed out that the complexity of the minute biochemical reactions required at a molecular level for light sensitivity still defies explanation.

[69][failed verification][non-primary source needed] In an often misquoted[70] passage from On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin appears to acknowledge the eye's development as a difficulty for his theory.

Finally, via this same selection process, a protective layer of transparent cells over the aperture was differentiated into a crude lens, and the interior of the eye was filled with humours to assist in focusing images.

The basal body of the flagella has been found to be similar to the Type III secretion system (TTSS), a needle-like structure that pathogenic germs such as Salmonella and Yersinia pestis use to inject toxins into living eukaryote cells.

[95] Behe responded to Miller by asking "why doesn't he just take an appropriate bacterial species, knock out the genes for its flagellum, place the bacterium under selective pressure (for mobility, say), and experimentally produce a flagellum—or any equally complex system—in the laboratory?

[101] He further said that the advances in knowledge in the subsequent 10 years had shown that the complexity of intraflagellar transport for two hundred components cilium and many other cellular structures is substantially greater than was known earlier.

[106] Niall Shanks and Karl H. Joplin, both of East Tennessee State University, have shown that systems satisfying Behe's characterization of irreducible biochemical complexity can arise naturally and spontaneously as the result of self-organizing chemical processes.

[113][114][112][115] An example of a structure that is claimed in Dembski's book No Free Lunch to be irreducibly complex, but evidently has evolved, is the protein T-urf13,[116] which is responsible for the cytoplasmic male sterility of waxy corn and is due to a completely new gene.

Behe's book Darwin Devolves claims that things like this would take billions of years and could not arise from random tinkering, but the corn was bred during the 20th century.

When presented with T-urf13 as an example for the evolvability of irreducibly complex systems, the Discovery Institute resorted to its flawed probability argument based on false premises, akin to the Texas sharpshooter fallacy.

[118] Some critics, such as Jerry Coyne (professor of evolutionary biology at the University of Chicago) and Eugenie Scott (a physical anthropologist and former executive director of the National Center for Science Education) have argued that the concept of irreducible complexity and, more generally, intelligent design is not falsifiable and, therefore, not scientific.

[97][needs update] Other critics take a different approach, pointing to experimental evidence that they consider falsification of the argument for intelligent design from irreducible complexity.

[124] Other critics describe Behe as saying that evolutionary explanations are not detailed enough to meet his standards, while at the same time presenting intelligent design as exempt from having to provide any positive evidence at all.

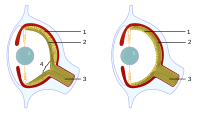

(a) A pigment spot

(b) A simple pigment cup

(c) The simple optic cup found in abalone

(d) The complex lensed eye of the marine snail and the octopus