Irreligion

It encompasses a wide range of viewpoints drawn from various philosophical and intellectual perspectives, including atheism, agnosticism, religious skepticism, rationalism, secularism, and non-religious spirituality.

These perspectives can vary, with individuals who identify as irreligious holding diverse beliefs about religion and its role in their lives.

In many countries censuses and demographic surveys do not separate atheists, agnostics and those responding "nothing in particular" as distinct populations, obscuring significant differences that may exist between them.

[19] A 2022 Gallup International Association (GIA) survey, done in 61 countries, reported that 62% of respondents said they are religious, one in four that they aren't, 10% that they're atheists and the rest are not sure.

[26] The term irreligion is a combination of the noun religion and the ir- form of the prefix in-, signifying "not" (similar to irrelevant).

[...] In contemporary usage, it is increasingly employed as a synonym for unbelief [...]"[28][29] Sociologist Colin Campbell also describes it as "deliberate indifference towards religion", in his 1971 Towards a Sociology of Irreligion.

Signatories to the convention are barred from "the use of threat of physical force or penal sanctions to compel believers or non-believers" to recant their beliefs or convert.

In 2020, the countries with the highest percentage of "Non-Religious" ("Term encompassing both (a) agnostics; and (b) atheists") were North Korea, the Czech Republic and Estonia.

[44] Some boadly religious practices continue to play a significant role in the lives of a substantial shares of the Chinese population.

[44] Determining objective irreligion, as part of societal or individual levels of secularity and religiosity, requires a high degree of cultural sensitivity from researchers.

[15]: 59 This is especially the case where religion has very deep-seated religious roots in a culture, such as with Christianity in Europe, Islam in the Middle East, Hinduism in India, and Buddhism in South-east Asia.

Vice versa, many American Jews share the worldviews of nonreligious people though affiliated with a Jewish denomination, and in Russia, growing identification with Eastern Orthodoxy is mainly motivated by cultural and nationalist considerations, without much concrete belief.

[47] In the United States, the majority of the "Nones", those without a religious affiliation, have belief in a god or higher power, spiritual forces beyond the natural world, and souls.

[19] In their 2013 essay, Ariela Keysar and Juhem Navarro-Rivera estimated there were about 450 to 500 million nonbelievers, including both "positive" and "negative" atheists, or approximately 7% of the world population.

[57][10] Pew states that religious areas are experiencing the fastest growth because of higher fertility and younger populations.

[10][58] By 2060, Pew says the number of unaffiliated will increase by over 35 million, but the overall population-percentage will decrease to 13% because the total population will grow faster.

[59][60] This would be mostly because of relatively old age and low fertility rates in less religious societies such as East Asia, particularly China and Japan, but also Western Europe.

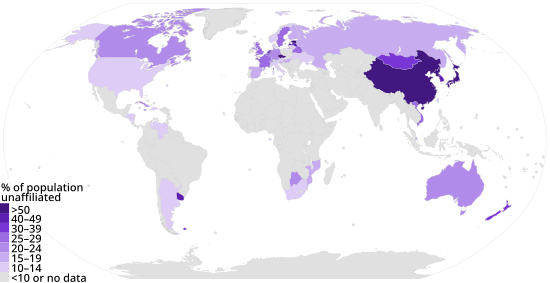

[17][18]: 24 The Pew Research Centre in the table below reflects "religiously unaffiliated" in 2010 which "include atheists, agnostics, and people who do not identify with any particular religion in surveys".

The Zuckerman data on the table below only reflect the number of people who have an absence of belief in a deity only (atheists, agnostics).

[6] Past influential thinkers from Karl Marx to Max Weber to Émile Durkheim thought that the spread of scientific knowledge would dispel religion throughout the world.

[5]: 110 Political scientists Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris argue faith is "more emotional than cognitive", and both advance an alternative thesis termed "existential security."

They claim that increased poverty and chaos make religious values more important to a society, while wealth and security diminish its role.

As need for religious support diminishes, there is less willingness to "accept its constraints, including keeping women in the kitchen and gay people in the closet".

[66] In a study of religious trends in 49 countries (they contained 60 percent of the world’s population) from 1981 to 2007, Inglehart and Norris found an overall, but not universal, increase in religiosity.

[5]: 112 The United States was a dramatic example of declining religiosity – with the mean rating of importance of religion dropping from 8.2 to 4.6 – while India was a major exception.

[67] Inglehart and Norris speculate that the decline in religiosity comes from a decline in the social need for traditional gender and sexual norms, ("virtually all world religions instilled" pro-fertility norms such as "producing as many children as possible and discouraged divorce, abortion, homosexuality, contraception, and any sexual behavior not linked to reproduction" in their adherents for centuries) as life expectancy rose and infant mortality dropped.

They also argue that the idea that religion was necessary to prevent a collapse of social cohesion and public morality was belied by lower levels of corruption and murder in less religious countries.

They argue that both of these trends are based on the theory that as societies develop, survival becomes more secure: starvation, once pervasive, becomes uncommon; life expectancy increases; murder and other forms of violence diminish.

As this level of security rises, there is less social/economic need for the high birthrates that religion encourages and less emotional need for the comfort of religious belief[5] Change in acceptance of "divorce, abortion, and homosexuality" has been measured by the World Values Survey and shown to have grown throughout the world outside of Muslim-majority countries.

[5] Several very comprehensive surveys in the Middle East and Iran have come to similar conclusions: there is an increase in secularization and growing calls for reforms in religious political institutions.