Isaac Perrins

A man reputed to possess prodigious strength but a mild manner, he fought and lost one of the most notorious boxing matches of the era, a physically mismatched contest against the English Champion Tom Johnson.

During the period when he was prizefighting Perrins worked for Boulton and Watt, manufacturers of steam engines, based at their Soho Foundry, Birmingham, but also travelled around the country and at times acted as an informant on people who were thought to have breached his employer's patents.

[2] From a legal standpoint such fights ran the risk of being classified as disorderly assemblies but in practice the authorities were concerned mainly about the number of criminals congregating there.

The patronage of the aristocracy – including royal princes and dukes – and other wealthy people ensured that any legal scrutiny was generally benign, in particular because fights could take place on private estates.

Prizefighting in early 18th-century England took many forms rather than just pugilism, which was referred to by noted swordsman and then boxing champion James Figg as "the noble science of defence".

[6] The appeal of prizefighting at that time has been compared to that of duelling, with historian Adrian Harvey saying that Patriotic writers often extolled the manly sports of the British, claiming that they reflected a courageous, robust, individualism in which the nation could take pride.

[4]Showell's Dictionary of Birmingham reported that although pugilism was long practised in the area the first local records it could find were of a prizefight on 7 October 1782 at Coleshill between Isaac Perrins, "the knock-kneed hammerman from Soho", and a professional called Jemmy Sargent.

[9] London was the premier centre for boxing because the aristocratic supporters of the sport dispersed to their country estates during the summer months but tended to congregate in the city for the winter period.

[1][8][13][15] Tony Gee has said that Perrins had overwhelming physical advantages but, owing to his naïvety, no clause was inserted in the articles of agreement to prevent "shifting" ...

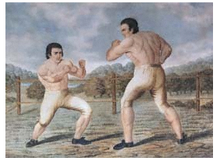

The event was recorded in The Gentleman's Magazine of that month ... a great boxing match took place ... between two bruisers, Perrins and Johnson: for which a turf stage had been erected 5 foot 6 inches high, and about 40 feet square.

The combatants set-to at one in the afternoon; and, after sixty-two rounds of fair and hard fighting, victory was declared in favour of Johnson, exactly at fifteen minutes after two.

[20] Chaloner has speculated that these may have been produced by his employers and says that they bear similarities with the work of a French die maker called Ponthon who was supplying the firm with industrial items from at least 1791.

[8] Indeed, these attempts, conducted by Daniel Mendoza, did not help the cause of his employment with Boulton and Watt as the firm thought that they were a distraction and expressed concern regarding his commitment to his work.

[1] Despite the brutal nature of prizefighting, it was the opinion of boxing historian Henry Downes Miles, in his book Pugilistica, that Perrins was of a "lamb-like disposition" and an intelligent, modest, discerning, and well-liked man.

In 1787 he visited Scotland, from where he reported on an invention by the Symingtons which might possibly have infringed a patent held by his employers, although Watt was disparaging of the device and its creator.

[26] His position in the firm was sufficiently elevated that he received business correspondence at the factory; for example, a letter to Perrins survives from October 1791, when a John Stratford sought his advice.

[25] This was not an unusual thing for retired prizefighters then: they often received the proceeds of a financial collection by their supporters to enable them to buy a licence to operate such premises and "today's fighter was merely tomorrow's publican in waiting".

Most of these sporting "pubs" had a large room at the back or upstairs, which was open one night a week (preferably Saturday), for public sparring, which was always conducted by a pugilist of some note.

[35] He was also running his own business engaged in general millwrighting and was still called upon by various Manchester engine owners who preferred to use his services for their machine erection and maintenance needs than those of Boulton and Watt.

The Register said that This pugilistic hero will ever be remembered for the well-contested battle he fought with the celebrated Johnson ... Perrins possessed most astonishing muscular power, which rendered him well calculated for a bruiser, to which was united a disposition the most placid and amiable.

[15][38] However, this announcement of his demise was premature as in fact he died on 6 January 1801 after contracting a fever because of his exertions during the rescue, which had occurred during a huge fire that burned all through the night of 10 December.

[8][21] The fire may be that described in The Annals of Manchester: "warehouses in Hodson Square were burnt down December 10, caused damages to the extent of £50,000, exclusive of the buildings".