Isaac Titsingh

Titsingh became a member of the Amsterdam Chirurgijngilde (English: Barber surgeon's guild) and received the degree of a Doctorate of Law from Leiden University in January 1765.

Given the scarcity of such opportunities, Titsingh's informal contacts with bakufu officials of Rangaku scholars in Edo may have been as important as his formal audiences with the shogun, Tokugawa Ieharu.

During his first audience with Ieharu in Edo from 25 March 1780 until 5 April 1780, he met a lot of Japanese daimyo with whom he later established vivid letter correspondence.

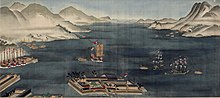

[11] There were no Dutch shipments from Batavia in 1782 due to the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, and thus the trading post in Dejima was cut off from communication with Java during this year.

[12] Titsingh stayed a total of three years and eight months in Japan before finally leaving Nagasaki at the end of November 1784 to return to Batavia, where he arrived on 3 January 1785.

[14] Titsingh's return to Batavia led to new positions as Ontvanger-Generaal (Treasurer) and later as Commissaris ter Zee (Maritime Commissioner).

In Peking (now Beijing), the Titsingh delegation included Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest[16] and Chrétien-Louis-Joseph de Guignes,[17] whose complementary accounts of this embassy to the Chinese court were published in the US and Europe.

[2] Titsingh's gruelling, mid-winter trek from Canton (now Guangzhou) to Peking allowed him to see parts of inland China which had never before been accessible to Europeans.

By Chinese standards, Titsingh and his delegation were received with uncommon respect and honors in the Forbidden City, and later in the Yuanmingyuan (the Old Summer Palace).

Among the Japanese books brought to Europe by Titsingh was a copy of Sangoku Tsūran Zusetsu (三国通覧図説, An Illustrated Description of Three Countries) by Hayashi Shihei (1738–93).

[25] After Rémusat's death, Julius Klaproth (1783–1835) at the Institut Royal in Paris was free in 1832 to publish his edited version of Titsingh's translation.

Due to his extensive private correspondence on religious as well as human topics and his endeavours in the exchanges between the outside world and his own, he can be considered as a true philosopher of the 18th century.

[27] Compared to the other VOC employees he was a polyglot, who spoke eight languages (Dutch, Latin, French, English, German, Portuguese, Japanese and Chinese).

As his own knowledge of the Sino-Japanese written characters was limited, he could only edit the translations of the Japanese accounts that were already prepared by himself and others in Dejima during his stay abroad.

The Batavian Academy of Arts and Sciences (Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen) published seven of Titsingh's articles about Japan.

[39] Looking at his private correspondence three mottos of his behaviour and values can be identified: the rejection of money, as it did not satisfy his enormous thirst of knowledge; an acknowledgment and consciousness of the brevity of life and wasting this precious time not with featureless activities; and his desire to die in calmness, as a "forgotten citizen of the world".

Therefore, he also acknowledged their intellectual competences and sophistication and contributed to an intense exchange of cultural knowledge between Japan and Europe in the 18th century.

[30][41] In a statistical overview derived from writings by and about Seki Takakau, OCLC/WorldCat encompasses roughly 90+ works in 150+ publications in 7 languages and 1,600+ library holdings.