Ishaq ibn Ibrahim al-Mus'abi

Abu al-Husayn Ishaq ibn Ibrahim[1] (Arabic: أبو الحسين إسحاق بن إبراهيم, died July 850) was a ninth-century official in the service of the Abbasid Caliphate.

A member of the Mus'abid family, he was related to the Tahirid governors of Khurasan, and was himself a prominent enforcer of caliphal policy during the reigns of al-Ma'mun, al-Mu'tasim, al-Wathiq, and al-Mutawakkil.

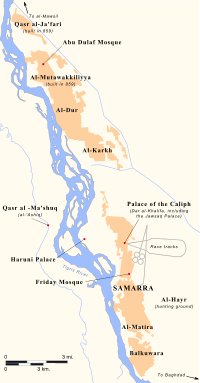

[2] In 822 he was appointed as chief of security (shurtah) of Baghdad, and over the next three decades he oversaw many of the major developments in that city, including the implementation of the mihnah or inquisition, the removal of the Abbasid central government to Samarra, and the suppression of the attempted rebellion of Ahmad ibn Nasr al-Khuza'i.

[6] In 830, following al-Ma'mun's decision to go on campaign against the Byzantines, the caliph designated Ishaq as his deputy over Baghdad, and also gave him control over the Sawad, Hulwan, and the Tigris districts.

[11] Shortly after al-Mu'tasim's accession in August 833, Ishaq was appointed as governor of the Jibal and was ordered to deal with the Khurramites of that region, who had assembled in the district of Hamadhan and defeated a previous army sent against them.

[13] In 840 he took into custody Mazyar, the captured rebel prince of Tabaristan, after the latter had arrived in Iraq; upon receiving him, Ishaq ordered him to be transported on an elephant and escorted him to the caliph in Samarra.

[15] Under the new caliph, he was called to preside over the cases of several mazalim officials during a general crackdown against the government bureaucracy in 843-4, and in 845 he oversaw the events of the festive season (mawsim) during the annual pilgrimage.

Resistance to these policies in Baghdad eventually culminated in 846, when supporters of orthodoxy led by Ahmad ibn Nasr al-Khuza'i formed plans to launch a popular rebellion against the central government.

[18] The accession of al-Mutawakkil (r. 847–861) represented a significant break in the policies and personnel of the central government; not only did the new caliph bring an end to the mihnah and abandon Mu'tazilism, but he also set about removing the senior military and civil officials that had dominated the administrations of his two predecessors.