Islamic State – West Africa Province

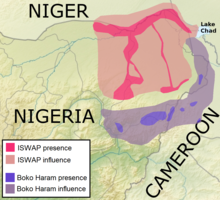

[4] ISWAP's origins date back to the emergence of Boko Haram, a Salafi jihadist movement centred in Borno State in northeastern Nigeria.

The movement launched an insurgency against the Nigerian government following an unsuccessful uprising in 2009, aiming at establishing an Islamic state in northern Nigeria,[5] and the neighbouring regions of Cameroon, Chad and Niger.

Its de facto leader Abubakar Shekau attempted to increase his international standing among Islamists by allying with the prominent Islamic State (IS) in March 2015.

[6][7][3] When the insurgents were subsequently defeated and lost almost all of their lands during the 2015 West African offensive by the Multinational Joint Task Force (MJTF), discontent grew among the rebels.

[6][7][8] Despite orders by the ISIL's central command to stop using women and children as suicide bombers as well as refrain from mass killings of civilians, Shekau refused to change his tactics.

[9] Researcher Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi summarized that the Boko Haram leader proved to be "too extreme even by the Islamic State's standards".

[12] It also changed its tactics, and attempted to win support by local civilians unlike Boko Haram which was known for its extensive indiscriminate violence.

At the same time, it experienced a violent internal dispute which resulted in the deposition of Abu Musab al-Barnawi and the execution of several commanders.

[13][14] In the course of 2020, the Nigerian Armed Forces repeatedly attempted to capture the Timbuktu Triangle[a] from ISWAP, but suffered heavy losses and made no progress.

[16] In April 2021, ISWAP overran a Nigerian Army base around Mainok, capturing armoured fighting vehicles including main battle tanks, as well as other military equipment.

[18] As a result, many Boko Haram fighters defected to ISWAP, and the group secured a chain of strongholds from Nigeria to Mali to southern Libya.

[22][23] The accuracy of this claim was questioned by Humangle Media researchers who gathered "multiple sources" suggesting that al-Barnawi had disappeared due to being promoted.

[24] Later that month, ISWAP suffered a defeat when attacking Diffa,[25] but successfully raided Rann, destroying the local barracks before retreating with loot.

Gudumbali is of strategic as well as symbolic importance, as it is placed at a well defendable position and was a major Boko Haram stronghold during the latter group's peak in power.

However, Nigerian troops immediately counter-attacked this time, retaking the settlement, destroying the local ISWAP headquarters, and a nearby night market associated with the group.

These splinter groups generally avoided fighting ISWAP directly, forcing the IS militants to expend considerable efforts to prevent defections and hunt for Boko Haram loyalists.

By January 2023, these clashes had ended in a substantial Boko Haram victory and the loss of several ISWAP bases at Lake Chad, though heavy fighting continued during the next months.

[38][39][40] From March to June 2023, ISWAP greatly increased the number of small-scale raids in Cameroon's Far North Region, targeting Gassama, Amchide, Fotokol, and Mora among other locations.

According to researcher Jacob Zenn, these attacks appeared to be mostly operations to gather loot and supplies as well as spread terror among civilians who refused to pay taxes to IS.

[43] In general, journalist Murtala Abdullahi argued that ISWAP mirrors the tendence of the IS core group to release little information on its leaders to the public, making even top commanders like Abu Musab al-Barnawi "elusive" figures.

There is no longer an overall wali, and the shura's head instead serves as leader of ISWAP's governorates, while the Amirul Jaish acts as chief military commander.

The group's sub-units (or governorates) were granted a considerable level of autonomy, allowing them to operate as they saw fit and to separately pledge allegiance to the new IS caliph, Abu al-Hussein al-Husseini al-Qurashi.

[64] As IS maintains to be a state despite having lost its territory in the Middle East, ISWAP's ability to run a basic government is ideologically important for all of IS.

Another sub-division or "cell", "Central Nigeria", became active in the following months, though this one appeared to solely operate as a guerrilla force instead of trying to capture territory.

[37] In addition to funding delivered by IS-Central and supportive international businessmen,[67] ISWAP collects taxes on agriculture, fishing, and trade in its territories.

[68] The group also provides various health services, builds public toilets and boreholes, and has implemented its own education system[24] based on Jihadist literature.