Islamic modernism

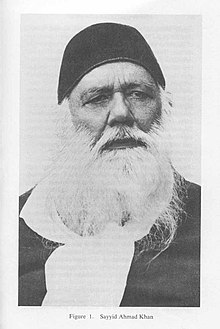

[5] Some themes in modern Islamic thought include: Syed Ahmad Khan sought to harmonize scripture with modern knowledge of natural science; to bridge "the gap between science and religious truth" by "abandoning literal interpretations" of scripture, and questioning the methodology of the collectors of sahih hadith, i.e. questioning whether what are thought to be some of the most accurately passed down narrations of what the Prophet said and did, are actually divinely revealed.

Similarly, when juxtaposed with the modern European notion of reformation, which primarily entails the alignment of conventional doctrines with Protestant and Enlightenment principles, it led to the emergence of two contrasting and symbiotic camps within the Muslim sphere: adaptionist modernists and literal fundamentalists.

[38] Mansoor Moaddel argues that modernism tended to develop in an environment where "pluralism" prevailed and rulers stayed out of religious and ideological debates and disputes.

[33] Islamic modernist discourse emerged as an intellectual movement in the second quarter of nineteenth century; during an era of wide-ranging reforms initiated across the Ottoman empire known as the Tanzimat (1839–1876 C.E).

The movement sought to harmonise classical Islamic theological concepts with liberal constitutional ideas and advocated the reformulation of religious values in light of drastic social, political and technological changes.

Major scholarly figures of this movement included the Grand Imam of al-Azhar Hassan al-Attar (d. 1835), Ottoman Vizier Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha (d. 1871), South Asian philosopher Sayyid Ahmad Khan (d. 1898), and Jamal al-Din Afghani (d. 1897).

While the Salafis opposed the autocratic policies of the Sultan Abdul Hamid II and the Ottoman clergy; they also intensely denounced the secularising and centralising tendencies of Tanzimat reforms brought forth by the Constitutionalist activists, accusing them of emulating Europeans.

Eventually the modernist intellectuals formed a secret society known as Ittıfak-ı Hamiyet (Patriotic Alliance) in 1865; which advocated political liberalism and modern constitutionalist ideals of popular sovereignty through religious discourse.

He founded the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh with the intent of producing "an educated elite of Muslims able to compete successfully with Hindus for jobs in the Indian administration".

After Abduh's death, his movement was catalysed by the demise of the Ottoman Caliphate in 1924 and promotion of secular liberalism – particularly with a new breed of writers being pushed to the fore including Egyptian Ali Abd al-Raziq's publication attacking Islamic politics for the first time in Muslim history.

He called for a revamping of the educational curriculum and became noteworthy for his role in revitalising the discourse of Maqasid al-Sharia (Higher Objectives of Islamic Law) in scholarly and intellectual ciricles.

In his treatise, Ibn Ashur called for a legal theory that is flexible towards 'urf (local customs) and adopted contextualised approach towards re-interpretation of hadiths based on applying the principle of Maqasid (objectives).

Following the First World War, Western colonialism of Muslim lands and the advancement of secularist trends; Islamic reformers felt betrayed by the Arab nationalists and underwent a crisis.

This schism was epitomised by the ideological transformation of Sayyid Rashid Rida, a pupil of 'Abduh, who began to resuscitate the treatises of Hanbali theologian Ibn Taymiyyah and became the "forerunner of Islamist thought" by popularising his ideals.

Rida transformed the Reformation into a puritanical movement that advanced Muslim identitarianism, pan-Islamism and preached the superiority of Islamic culture while attacking Westernisation.

According to the German scholar Bassam Tibi, "Rida's Islamic fundamentalism has been taken up by the Muslim Brethren, a right wing radical movement founded in 1928, which has ever since been in inexorable opposition to secular nationalism.

[53][54] Politics portal The modernist movement led by Jamal Al-Din al-Afghani, Muhammad 'Abduh, Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur, Syed Ahmad Khan, and to a lesser extent Mohammed al-Ghazali; shared some of the ideals of the conservative revivalist Wahhabi movement, such as endeavoring to "return" to the Islamic understanding of the first Muslim generations (Salaf) by reopening the doors of juristic deduction (ijtihad) that they saw as closed.

Modernists thought taqlid prevented the Muslims from flourishing because it got in the way of compatibility with the modern world, traditional revivalists simply because (they believed) it was impure.

The anti-colonial struggle to restore the Khilafah would become the top priority; manifesting in the formation of the Muslim Brotherhood, a revolutionary movement established in 1928 by the Egyptian school teacher Hassan al-Banna.

Backed by the Wahhabi clerical elites of Saudi Arabia, Salafis who advocated pan-Islamist religious conservatism emerged across the Muslim World, gradually replacing modernists during the decolonisation period,[66] and then dominating funding for Islam via petroleum export money starting in the 1970s.

[67]Islamic revivalists, such as Mahmud Shukri Al-Alusi (1856–1924 C.E), Muhammad Rashid Rida (1865–1935 C.E), and Jamal al-Din al-Qasimi (1866–1914 C.E), used Salafiyya as a term primarily to denote the traditionalist Sunni theology, Atharism.

[75][76] Apart from the Wahhabis of Najd, Athari theology could also be traced back to the Alusi family in Iraq, Ahl-i Hadith in India, and scholars such as Rashid Rida in Egypt.

This tendency led by Rida emphasized following the salaf al-salih and became known as the Salafiyya movement, which advocated a re-generation of pristine religious teachings of the early Muslim community.

[79] The progressive views of the early modernists Afghani and Abduh were soon replaced by the puritan Athari tradition espoused by their students; which zealously denounced the ideas of non-Muslims and secular ideologies like liberalism.

This theological transformation was led by Syed Rashid Rida who adopted the strict Athari creedal doctrines of Ibn Taymiyyah during the early twentieth century.

[80] Its traditionalist vision was adopted by the Wahhabi clerical establishment and championed by influential figures such as the Syrian-Albanian Hadith scholar Muhammad Nasiruddin al-Albani (d. 1999 C.E/ 1420 A.H).

[88] As Islamic Modernist beliefs were co-opted by secularist rulers and official `ulama, the Brotherhood moved in a traditionalist and conservative direction, as it drew more and more of those Muslims "whose religious and cultural sensibilities had been outraged by the impact of Westernisation" -- being "the only available outlet" for such people.

[89] The Brotherhood argued for a Salafist solution to the contemporary challenges faced by the Muslims, advocating the establishment of an Islamic state through implementation of the Shari'ah, based on Salafi revivalism.

The school of theology at Ankara University undertook this forensic examination with the aim of removing the centuries-old conservative cultural burden and rediscovering the spirit of reason in the original message of Islam.

The establishment of non-religious institutions of learning in India, Egypt and elsewhere, which Abduh encouraged, "opened the floodgates to secular forces which threatened Islam's intellectual foundations".