Islamization of the Sudan region

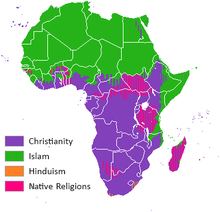

The Islamization of the Sudan region (Sahel)[1] encompasses a prolonged period of religious conversion, through military conquest and trade relations, spanning the 8th to 16th centuries.

Sufi orders played a significant role in the spread of Islam from the 9th to 14th centuries, and they proselytized across trade routes between North Africa and the sub-Saharan kingdom of Mali.

During the 19th century the Sanusi order was highly involved in missionary work with their missions focused on the spread of both Islam and textual literacy as far south as Lake Chad.

The problem of slavery in contemporary Africa remains especially pronounced in these countries, with severe divides between the Arabized population of the north and dark-skinned Africans in the south motivating much of the conflict, as these nations sustain the centuries-old pattern of hereditary servitude that arose following early Muslim conquests.

After the initial attempts at military conquest failed, the Arab commander in Egypt, Abd Allah ibn Saad, concluded the first in a series of regularly renewed treaties with the Nubians that governed relations between the two peoples for more than six hundred years with only brief interruptions.

The Arabs realized the commercial advantages of peaceful relations with Nubia and used the Baqt to ensure that travel and trade proceeded unhindered across the frontier.

Muslim pilgrims en route to Mecca traveled across the Red Sea on ferries from Aydhab and Suakin, ports that also received cargoes bound from India to Egypt.

Both groups formed a series of tribal shaykhdoms that succeeded the crumbling Christian Nubian kingdoms, and were in frequent conflict with one another and with neighboring non-Arabs.

By the mid-sixteenth century, Sennar controlled Al Jazirah and commanded the allegiance of vassal states and tribal districts as far north as the third cataract of the nile and as far south as the rainforests.

Sennar apportioned tributary areas into tribal homelands each one termed a dar (pl., dur), where the mek granted the local population the right to use arable land.

At the peak of its power in the mid-17th century, Sennar repulsed the northward advance of the Nilotic Shilluk people up the White Nile and compelled many of them to submit to Funj authority.

To implement this policy, Badi introduced a standing army of slave soldiers that would free Sennar from dependence on vassal sultans for military assistance, and would provide the mek with the means to enforce his will.

Another reason for Sennar's decline may have been the growing influence of its hereditary viziers (chancellors), chiefs of a non-Funj tributary tribe who managed court affairs.

In 1761, the vizier Muhammad Abu al Kaylak, who had led the Funj army in wars, carried out a palace coup, relegating the sultan to a figurehead role.

However, large-scale religious conversions did not occur until the reign of Ahmad Bakr (1682–1722), who imported teachers, built mosques, and compelled his subjects to become Muslims.

In the eighteenth century, several sultans consolidated the dynasty's hold on Darfur, established a capital at Al-Fashir, and contested the Funj for control of Kurdufan.