Isospin

The name of the concept contains the term spin because its quantum mechanical description is mathematically similar to that of angular momentum (in particular, in the way it couples; for example, a proton–neutron pair can be coupled either in a state of total isospin 1 or in one of 0[1]).

Before the concept of quarks was introduced, particles that are affected equally by the strong force but had different charges (e.g. protons and neutrons) were considered different states of the same particle, but having isospin values related to the number of charge states.

[2] A close examination of isospin symmetry ultimately led directly to the discovery and understanding of quarks and to the development of Yang–Mills theory.

Isospin symmetry remains an important concept in particle physics.

To a good approximation the proton and neutron have the same mass: they can be interpreted as two states of the same particle.

The mathematical properties of this coordinate are completely analogous to intrinsic spin angular momentum.

Hadrons with the same quark content but different total isospin can be distinguished experimentally, verifying that flavour is actually a vector quantity, not a scalar (up vs down simply being a projection in the quantum mechanical z axis of flavour space).

For example, a strange quark can be combined with an up and a down quark to form a baryon, but there are two different ways the isospin values can combine – either adding (due to being flavour-aligned) or cancelling out (due to being in opposite flavour directions).

Like the case for regular spin, the isospin operator I is vector-valued: it has three components Ix, Iy, Iz, which are coordinates in the same 3-dimensional vector space where the 3 representation acts.

The third coordinate (z), to which the "3" subscript refers, is chosen due to notational conventions that relate bases in 2 and 3 representation spaces.

The discovery of charm, bottomness and topness could lead to further expansions up to SU(6) flavour symmetry, which would hold if all six quarks were identical.

However, the very much larger masses of the charm, bottom, and top quarks means that SU(6) flavour symmetry is very badly broken in nature (at least at low energies), and assuming this symmetry leads to qualitatively and quantitatively incorrect predictions.

[4] In 1932, Werner Heisenberg[5] introduced a new (unnamed) concept to explain binding of the proton and the then newly discovered neutron (symbol n).

Heisenberg's theory had several problems, most notable it incorrectly predicted the exceptionally strong binding energy of He+2, alpha particles.

The power of isospin symmetry and related methods comes from the observation that families of particles with similar masses tend to correspond to the invariant subspaces associated with the irreducible representations of the Lie algebra SU(2).

In this context, an invariant subspace is spanned by basis vectors which correspond to particles in a family.

Under the action of the Lie algebra SU(2), which generates rotations in isospin space, elements corresponding to definite particle states or superpositions of states can be rotated into each other, but can never leave the space (since the subspace is in fact invariant).

In the case of isospin, this machinery is used to reflect the fact that the mathematics of the strong force behaves the same if a proton and neutron are swapped around (in the modern formulation, the up and down quark).

Isospin was introduced in order to be the variable that defined this difference of state.

In the isospin picture, the four Deltas and the two nucleons were thought to simply be the different states of two particles.

The Delta baryons are now understood to be made of a mix of three up and down quarks – uuu (Δ++), uud (Δ+), udd (Δ0), and ddd (Δ−); the difference in charge being difference in the charges of up and down quarks (+2/3 e and −1/3 e respectively); yet, they can also be thought of as the excited states of the nucleons.

The rho mesons were discovered a short time later, and were quickly identified as Sakurai's vector bosons.

The fact that the diagonal isospin current contains part of the electromagnetic current led to the prediction of rho-photon mixing and the concept of vector meson dominance, ideas which led to successful theoretical pictures of GeV-scale photon-nucleus scattering.

Once the kaons and their property of strangeness became better understood, it started to become clear that these, too, seemed to be a part of an enlarged symmetry that contained isospin as a subgroup.

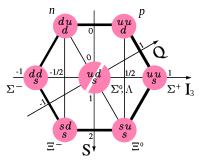

The larger symmetry was named the Eightfold Way by Murray Gell-Mann, and was promptly recognized to correspond to the adjoint representation of SU(3).

That is, the (spin-up) proton wave function, in terms of quark-flavour eigenstates, is described by[2]

Although these superpositions are the technically correct way of denoting a proton and neutron in terms of quark flavour and spin eigenstates, for brevity, they are often simply referred to as "uud" and "udd".

The derivation above assumes exact isospin symmetry and is modified by SU(2)-breaking terms.

[8] In 1961 Sheldon Glashow proposed that a relation similar to the Gell-Mann–Nishijima formula for charge to isospin would also apply to the weak interaction:[9][10]: 152

By contrast (strong) isospin connects only up and down quarks, acts on both chiralities (left and right) and is a global (not a gauge) symmetry.