Ixodes holocyclus

Paralysis ticks are found in many types of habitat, particularly areas of high rainfall such as wet sclerophyll forest and temperate rainforest.

[4] One of the earliest Australian references to ticks as a problem in human disease is found in the journal kept by Captain William Hovell during his 1824–1825 journey with Hamilton Hume from Lake George to Port Phillip.

He remarked on "the small insect called the tick, which buries itself in the flesh, and would in the end destroy either man or beast if not removed in time".

[5][6] James Backhouse, a well-travelled Quaker during the early colonial period, gave the following account:[7] "At Colongatta, in Shoal Haven...district, which, like that of Illawarra, is much more favorable for the grazing of horned cattle than for sheep.

Among the enemies of the latter in these rich, coast lands, is the Wattle Tick, a hard flat insect of a dark colour, about the tenth of an inch in diameter, and nearly circular, in the body; it insinuates itself beneath the skin, and destroys, not only sheep, but sometimes foals and calves.

Under natural conditions, the time taken for an adult female to engorge while on the host varies from 6 to 21 days, the period being longest in cool weather.

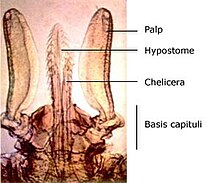

Diagnosis: A very large tick when fully engorged; scutum about as long as broad and broadest a little posterior to mid length, with strong lateral carinae; capitulum relatively long porose areas deep, cornua usually absent, but when present at most only mild and rounded; auriculae present; hypostome lanceolate, dentition mainly 3/3; no sternal plate; anal grooves meeting at a point behind; all coxae with an external spur decreasing in size posteriorly; trochanters III and IV usually with small, pointed ventral spurs.

Fully engorged specimens broadly oval, attaining 13.2 × 10.2 mm, living ticks with blue-grey alloscutum, the dorsum light in colour, a dark band in region of marginal groove.

Basis dorsally 0.60–0.68 mm in width, the lateral submarginal fields swollen and frequently delimited from the depressed, median field by ill-defined carinae; posterior margin sinuous, posterolateral angles swollen, sometimes mildly salient; porose areas large, deep subcircular or oval, the longer axis directed anteriorly, interval frequently depressed, at most about the width of one; basis ventrally with posterior margin rounded and with well-defined, blunt, retrograde auriculae.

Diagnosis: Body measurements less than 3.0 × 2.5 mm; lateral grooves completely encircling conscutum, no lateral carinae; punctuations fine; basis capituli punctate dorsally, palpi short and very broad; hypostome dentition 2/2, with rounded teeth; anal plate bluntly pointed behind; adanal plate curving inwardly to a point; coxae with well-defined spurs decreasing in size posteriorly; trochanters III and IV frequently with small, ventral spurs.

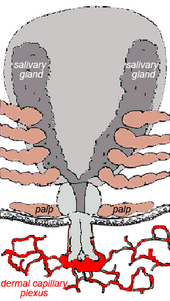

It is thought by some experimenters that the residual toxin located in this granuloma is at least partially responsible for the increasing paralysis which occurs after the tick is removed.

The kinds of effects caused by bites of Ixodes holocyclus vary in their frequency according to the type of host and whether the tick is at the stage of larva, nymph or adult.

At the site of a bite by an adult female Ixodes holocyclus one can expect there to be local numbness and an itchy lump which lasts for several weeks.

Repeated infestation with larvae, as occurs in rural and wooded suburban areas where bandicoots are common, rapidly leads to the development of hypersensitivity.

Dramatic local redness, numbness, swelling and itching may develop within 2–3 hours of attachment of even one larva if a person has been sensitised by a previous bite.

Often, attachment may provoke little or no response and the patient may be unaware of the presence of a tick for some days until eventually minor itching leads to its discovery.

[35] The induced allergy is unusual in that the onset of the allergic reaction, which ranges from mild stomach symptoms to life-threatening anaphylaxis (skin rashes, swollen tongue and serious drop in blood pressure), can occur up to 3 to 6 hours after eating mammalian meat (typically beef, lamb or pork) and often many months after the tick bite.

Early work suggested that the most neurotoxic fraction was a protein (molecular weight 40–60 kilodaltons, stable when freeze dried, originally named holocyclotoxin).

Spiders and scorpions have retained toxins and developed specialised delivery structures (fangs and telsons) while mites and ticks have lost this feature.

In colder weather the feeding process is slowed considerably and some animals may not show significant signs of paralysis for as long as two weeks.

Furthermore, dogs rarely show significant signs until the adult female has engorged to a width of at least 4 mm (measured at the level of the spiracles; see photo of lateral view of Ixodes holocyclus).

Early signs include lethargy, loss of appetite, apparent groaning when lifted, altered voice (bark or meow), noisy panting, coughing, drooling of saliva, gagging, regurgitation (dogs) and enlarged pupils (cats).

Ancillary treatments may include: Prevention of tick paralysis is mostly achieved by a combination of daily searching and the use of tick-repelling or tick-killing agents.

Application of methylated spirit, nail polish remover, turpentine or tea-tree oil is thought to irritate the tick and make it inject more of the noxious substances.

It has been noted that, when Ixodes holocyclus is forcibly extracted, the feeding tube (the hypostome) is usually damaged, which suggests that part of its tip remains embedded in the skin.

Rickettsia australis is an obligate intracellular bacterial parasite that proliferates within the endothelial cells of small blood vessels, causing a vasculitis.

Some vector competence studies have been undertaken on Ixodes holocyclus with respect to the Lyme disease pathogen Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto (a United States strain).

Cases of Lyme-like disease are being diagnosed on the basis of clinical signs (often musculoskeletal, chronic fatigue, neurological and dermatological), exclusion of other infections, serology (which is supportive but not conclusive), and response to antibiotic treatment.

This putative Australian form of Lyme-like borreliosis is associated with a different clinical picture from true Lyme disease of North America.

[71][72][73][74] Early symptoms in the first four weeks after a tick bite include a rash or red patch that gradually expands over several days.