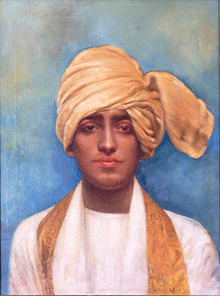

Jiddu Krishnamurti

Adopted by members of the Theosophical tradition as a child, he was raised to fill the advanced role of World Teacher, but in adulthood he rejected this mantle and distanced himself from the related religious movement.

His supporters — working through non-profit foundations in India, Britain, and the United States — oversee several independent schools based on his views on education, and continue to distribute his thousands of talks, group and individual discussions, and writings in a variety of media formats and languages.

Mary Lutyens determines it to be 11 May 1895,[2] but Christine Williams notes the unreliability of birth registrations in that period and that statements claiming dates ranging from 4 May 1895 to 25 May 1896 exist.

Leadbeater and a small number of trusted associates undertook the task of educating, protecting, and generally preparing Krishnamurti as the "vehicle" of the expected World Teacher.

Krishnamurti (often later called Krishnaji)[22] and his younger brother Nityananda (Nitya) were privately tutored at the Theosophical compound in Madras, and later exposed to an opulent life among a segment of European high society as they continued their education abroad.

[28] Another biographer describes the daily program imposed on him by Leadbeater and his associates, which included rigorous exercise and sports, tutoring in a variety of school subjects, Theosophical and religious lessons, yoga and meditation, as well as instruction in proper hygiene and in the ways of British society and culture.

[31] His public image, cultivated by the Theosophists, "was to be characterized by a well-polished exterior, a sobriety of purpose, a cosmopolitan outlook and an otherworldly, almost beatific detachment in his demeanor.

"[32] It was apparently clear early on that he "possessed an innate personal magnetism, not of a warm physical variety, but nonetheless emotive in its austerity, and inclined to inspire veneration.

"[33] However, as he was growing up, Krishnamurti showed signs of adolescent rebellion and emotional instability, chafing at the regimen imposed on him, visibly uncomfortable with the publicity surrounding him, and occasionally expressing doubts about the future prescribed for him.

[37] Meanwhile, Krishnamurti had for the first time acquired a measure of personal financial independence, thanks to a wealthy benefactress, American Mary Melissa Hoadley Dodge, who was domiciled in England.

[38] After the war, Krishnamurti embarked on a series of lectures, meetings and discussions around the world, related to his duties as the Head of the OSE, accompanied by Nitya, by then the Organizing Secretary of the Order.

The initial events happened in two distinct phases: first a three-day spiritual experience, and two weeks later, a longer-lasting condition that Krishnamurti and those around him referred to as the process.

[50] Following — and apparently related to — these events[51] the condition that came to be known as the process started to affect him, in September and October that year, as a regular, almost nightly occurrence.

[53] Krishnamurti describes it in his notebook as typically following an acute experience of the process, for example, on awakening the next day: ... woke up early with that strong feeling of otherness, of another world that is beyond all thought ... there is a heightening of sensitivity.

[58]As news of these mystical experiences spread, rumours concerning the messianic status of Krishnamurti reached fever pitch as the 1925 Theosophical Society Convention was planned, on the 50th anniversary of its founding.

"Extraordinary" pronouncements of spiritual advancement were made by various parties, disputed by others, and the internal Theosophical politics further alienated Krishnamurti.

[68] He stated that he had made his decision after "careful consideration" during the previous two years, and that: I maintain that truth is a pathless land, and you cannot approach it by any path whatsoever, by any religion, by any sect.

"[71] Krishnamurti had denounced all organised belief, the notion of gurus, and the whole teacher-follower relationship, vowing instead to work on setting people "absolutely, unconditionally free.

"[69] There is no record of his explicitly denying he was the World Teacher;[72] whenever he was asked to clarify his position he either asserted that the matter was irrelevant[73] or gave answers that, as he stated, were "purposely vague".

[75] The subtlety of the new distinctions on the World Teacher issue was lost on many of his admirers, who were already bewildered or distraught because of the changes in Krishnamurti's outlook, vocabulary and pronouncements–among them Besant and Mary Lutyens' mother Emily, who had a very close relationship with him.

During this time he lived and worked at Arya Vihara, which during the war operated as a largely self-sustaining farm, with its surplus goods donated for relief efforts in Europe.

He met with many prominent religious leaders and scholars including Swami Venkatesananda, Anandamayi Ma, Lakshman Joo, Walpola Rahula, and Eugene Schalert.

In the early 1960s, he made the acquaintance of physicist David Bohm, whose philosophical and scientific concerns regarding the essence of the physical world, and the psychological and sociological state of mankind, found parallels in Krishnamurti's philosophy.

The two men soon became close friends and started a common inquiry, in the form of personal dialogues–and occasionally in group discussions with other participants–that continued, periodically, over nearly two decades.

Nevertheless, Krishnamurti met and held discussions with physicists Fritjof Capra and E. C. George Sudarshan, biologist Rupert Sheldrake, psychiatrist David Shainberg, as well as psychotherapists representing various theoretical orientations.

[92] The long friendship with Bohm went through a rocky interval in later years, and although they overcame their differences and remained friends until Krishnamurti's death, the relationship did not regain its previous intensity.

Krishnamurti had commented to friends that he did not wish to invite death, but was not sure how long his body would last (he had already lost considerable weight), and once he could no longer talk, he would have "no further purpose".

[citation needed] Krishnamurti was also concerned about his legacy, about being unwittingly turned into some personage whose teachings had been handed down to special individuals, rather than the world at large.

"[106] Notable individuals influenced by Krishnamurti include George Bernard Shaw, David Bohm, Jawaharlal Nehru, the Dalai Lama, Aldous Huxley, Alan Watts,[107] Henry Miller, Bruce Lee,[108] Terence Stamp,[109] Jackson Pollock,[110] Toni Packer,[111] Achyut Patwardhan,[112] Dada Dharmadhikari,[113] Derek Trucks,[114] U.G.

The four official Foundations continue to maintain archives, disseminate the teachings in an increasing number of languages, convert print to digital and other media, develop websites, sponsor television programs, and organise meetings and dialogues of interested persons around the world.