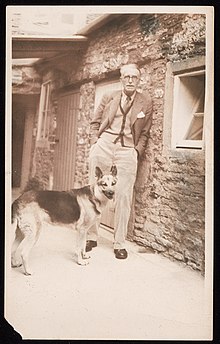

J. R. Ackerley

Starting with the BBC the year after its founding in 1927, he was promoted to literary editor of The Listener, its weekly magazine, where he served for more than two decades.

[3] His father, (Alfred)[citation needed] Roger Ackerley, was a successful fruit merchant known as the "Banana King" of London.

Roger Ackerley was first married to a young Swiss woman of wealthy parentage named (Charlotte) Louise Burckhardt (1862–1892) who died probably of tuberculosis, before they had children.

[4][5][6][7] His mother was Janetta Aylward (known as Netta), an actress whom Roger met in Paris; the two returned to London together.

He described himself as "a chaste, puritanical, priggish, rather narcissistic little boy, more repelled than attracted to sex, which seemed to me a furtive, guilty, soiling thing, exciting, yes, but nothing whatever to do with those feelings which I had not yet experienced but about which I was already writing a lot of dreadful sentimental verse, called romance and love.

He was promoted to captain,[citation needed] when his elder brother Peter, also an officer in the East Surrey Regiment, arrived in France in December 1916.

Though Peter got back to the British lines, Ackerley never saw him again, as he was killed on 7 August 1918, two months before the end of the war.

[15] From the autumn of 1919, Ackerley attended Magdalene College, Cambridge, where he was in the same year as Patrick Blackett, Geoffrey Webb and Kingsley Martin.

[16] After graduating with a third-class degree in English in 1921, he moved to London, where he enjoyed the cosmopolitan capital and continued to write.

In 1923 his play The Prisoners of War was included in a collection of young British writers, so he began to receive some recognition.

With his play having trouble finding a producer and feeling generally adrift and distant from his family, Ackerley turned to Forster for guidance.

Forster, whom he knew from A Passage to India, arranged a position as secretary to the Maharaja of Chhatarpur, Vishwanath Singh.

The Maharaja was homosexual, and His Majesty's obsessions and dalliances, along with Ackerley's observations about Anglo-Indians, account for much of the humour of the work.

He worked in the Talks Department, which arranged radio lectures by prominent scholars and public figures.

He served in this position until 1959, discovering and promoting many younger writers, including W. H. Auden, Christopher Isherwood, Philip Larkin, and Stephen Spender.

He revised Hindoo Holiday (1952), completed My Dog Tulip (1956) and We Think the World of You (1960), and worked on drafts of My Father and Myself.

"[18] In 1962, We Think the World of You won the W. H. Smith Literary Award, which came with a substantial cash prize, but this did little to stir him from his grief.

Ackerley was a "twank", a term used by sailors and guardsmen to describe a man who paid for their sexual services.

W. H. Auden, in his review of My Father and Myself, speculates that Ackerley enjoyed the "brotherly"[26] sexual act of mutual masturbation rather than penetration.

Shortly afterward Ackerley found a sealed note from his father addressed to him, which concluded: "I am not going to make any excuses, old man.

Roger used to visit his daughters three or four times a year when he was supposedly travelling on business, and sometimes when out to walk his first family's dog.

Ackerley described the lives of his half-sisters in his 1968 memoir: "They had no parental care, no family life, no friends."

In 1980 the BBC series Omnibus profiled Ackerley in a dramatised biography starring Benjamin Whitrow.