Jacques de Falaise

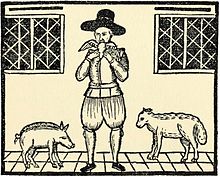

First hired by conjurer Louis Comte at his Paris theater in 1816, he became famous for a few years for his "polyphagic experiments", during which he ingested nuts, pipes, unshelled hard-boiled eggs, flowers with their stems, watches, and live animals such as mice, sparrows, eels, and crayfish.

His autopsy was the subject of a memoir widely circulated in Europe, which concluded that Jacques de Falaise was not endowed with exceptional digestive organs, and that he indulged in his exercises out of a desire to shine, rather than a depraved appetite.

Almost nothing is known about the first sixty years of his life, other than that he worked as a quarryman in the plaster quarries of Montmartre,[2][3] a trade that enabled him to develop "very considerable muscular strength"[4] and "robust health",[1] yet he never "felt the need to satisfy his hunger with disgusting or bizarre objects".

According to the 1820 Notice devoted to him by an anonymous author, it happened, on an unspecified date, that, as a game, he hid a bride's chain and locket in his mouth, then, in order not to be discovered, he swallowed them and declared: "Vous voyais ben que je n'lons point" ("You could see that I don't have anything").

[1] Having discovered this curious talent, Jacques Simon repeated the experiment several times, swallowing "corks and hard-boiled eggs with their shells",[6] "keys, crosses, rings", then "live animals, which passed through with the same ease".

[6] Jacques Simon's artistic career was an indirect consequence of the success of a trio of Indian jugglers who, "after having won the admiration of London",[8][9][10] performed in Paris, rue de Castiglione, during the winter of 1815-1816.

[16] English traveler Stephen Weston[note 5] summed up Jacques's joy by pastiching a tirade by Francaleu in La Métromanie: In my belly one fine day this talent was found,And I was sixty years old when it happened to me.

[22] To the amazement of the audience, he swallowed for a quarter of an hour,[23] "very resolutely"[16] and "with an air of bliss painted on his face",[24] whole potatoes or walnuts, unshelled eggs, a pipe bowl, small shot glasses, a watch with its chain, three cards rolled together, which he " swallowed without tearing them or crushing them with his teeth",[25] a rose, "with its leaves, its long stem, and its thorns",[16] but also live animals, such as a sparrow, a white mouse, a frog, a crayfish, an eel or a snake,[8][16][24][26][6][19] never vomiting what he ingested in this way.

[16] Describing Jacques as an "homophagus",[note 8] Pierre-François Percy and Charles Nicolas Laurent added that "his face showed no trace of painful digestion; it was pale and very wrinkled; he ate a pound of cooked meat at each of his meals, and drank two bottles of wine.

According to the latter, "on one occasion, an eel went up through the oesophagus, to the posterior opening of the nasal cavity, and caused great pain there by the efforts it made to find a way out; finally, it entered the back of the mouth.

[32] The grief of this loss and the abuse of his stomach led to a further deterioration in his health: he was again treated at the Beaujon hospital for gastroenteritis, this time aggravated, and underwent a long and painful convalescence.

[40] In the early 19th century, however, the term coexisted with "omophagia",[note 8] or "homophagia" as Pierre-François Percy and Charles Nicolas Laurent spelled it in the Dictionnaire des sciences médicales edited by Panckoucke[6]—to which the article "Polyphage", also signed by them,[45] referred—and "cynorexia" or canine hunger.

[46] As Tarrare had died of "purulent and infectious diarrhea, announcing a general suppuration of the abdominal viscera",[44] there was some hesitation about performing an autopsy, but Dr. Tessier "braving the disgust and danger of such an autopsy, decided to investigate, which only resulted in showing him putrefied entrails, bathed in pus, blended together, with no trace of foreign matter", a liver "excessively large, without consistency, and in a state of putrefaction", a gallbladder of equally considerable volume, and a stomach "flaccid and strewn with ulcerous plaques, covered almost the entire lower abdominal region".

[56] Pierre-François Percy and Charles Nicolas Laurent, two doctors specializing in polyphagia, in particular the case of Tarrare, who observed Jacques de Falaise in 1816 at the Théâtre Comte, confined themselves to describing his "experiments".

[6] German forensic pathologist Johann Ludwig Casper testified that he had observed him ingest "a whole raw egg, a live sparrow, a live mouse, a rolled card" in the space of a quarter of an hour, and was convinced that there was no trickery involved; He also observed that the subject hardly seemed "disturbed" by this "horrible meal", that "his ingesta remained in the body a normal time and went away half digested" and that he "enjoyed a considerable, but not unnatural, quantity of ordinary food".

Dr. Beaudé, who drew "very important conclusions"[62][63][64][65][66] from the autopsy (communicated to the Paris Medical Athenaeum on April 15, 1826), noted that the pharynx, esophagus and pylorus were of "considerable extent", which, in his opinion, explained the subject's facility in swallowing large objects, but also resulted from it.

[68] Beaudé noted, on the other hand, that the mucous membrane of the ileum was "almost destroyed"; that "the other tunics of the intestine were so thinned that through these points one observed a very marked transparency"; and that the cecum showed "large and numerous scars", likely consequences of the two previous gastroenteritises.

[70] Consequently, the "polyphagic" feats were to be attributed, in his view, solely to the fact that he had "overcome the remoteness and disgust that one ordinarily experiences when ingesting these kinds of bodies in the stomach".

While the latter was the victim of insatiable gluttony resulting from an illness, the former manifested an "acquired disposition": "Jacques de Falaise was in no way stimulated by an extraordinary appetite; he only indulged in his exercises out of boasting or desire for gain, whereas Tarrare gave in to an irresistible need that he sought to satisfy at all costs".

[40] Several nineteenth-century authors equated polyphagia with an extreme form of gluttony—such as Baudelaire, who had the lover of a gluttonous mistress say that he could have made a fortune "by showing her at fairs as a polyphagous monster"—or even with omophagia.

Because his "polyphagia" was the result of a deliberate habitual practice[63] and not a malformation, Jacques de Falaise is considered the "ancestor" of a circus and music hall specialty, the "mérycistes".