Jallikattu

[8] The modern term jallikattu (ஜல்லிக்கட்டு) or sallikattu (சல்லிக்கட்டு) is derived from salli ('coins') and kattu ('package'), which refers to a prize of coins that is tied to the bull's horns and that participants attempt to retrieve.

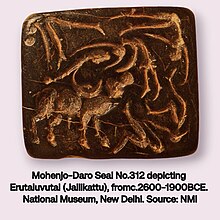

[1] It was a cultural ritual among the Ayar tribal people[10][11] who lived in the ‘Mullai’ geographical region of the ancient Tamil Nadu.

[14] A cave painting in white kaolin discovered near Madurai depicting a lone man trying to control a bull is estimated to be about 1,500 years old.

R. Krishnamurthy, president of the South Indian Numismatic Society, estimated that the coin belongs to third or fourth century BCE.

[16] Jallikkattus are very common between Thanjavur and Tiruchirappalli in the north and Tirunelveli and Ramanathapuram in the south, a region centered around the city of Madurai and populated for the most part by the Mukkulathor castes, who are the main participants in this ritual sport.

[20] In the Pudukkottai State, the Jallikattu was considered as a quasi religious function to be conducted to propitiate the village deities, and was usually held on any day after the Thai Pongal when harvesting was over and before the commencement of the Tamil New Year.

[31] During attempts to subdue the bull, they are stabbed by various implements such as knives or sticks, punched, jumped on and dragged to the ground.

[32][33] Protestors claim that jallikattu is promoted as bull taming, however, others suggest it exploits the bull's natural nervousness as prey animals by deliberately placing them in a terrifying situation in which they are forced to run away from the competitors which they perceive as predators and the practice effectively involves catching a terrified animal.

[42][43] The Indian Minister of Women and Child Development Maneka Gandhi denied the claim by jallikattu aficionados that the sport is only to demonstrate the "Tamil love for the bull", citing that the Tirukkural does not sanction cruelty to animals.

On 27 November 2010, the Supreme Court permitted the Government of Tamil Nadu to allow jallikattu for five months in a year and directed the District Collectors to make sure that the animals that participate in jallikattu are registered to the Animal Welfare Board and in return the Board would send its representative to monitor the event.

[47][51] The court also asked the Government of India to amend the law on preventing cruelty to animals to bring bulls within its ambit.

[58] On 16 January 2016, the World Youth Organization (WYO) protested at Chennai against the stay on the order overturning ban on conducting jallikattu in Tamil Nadu.

[69] Numerous jallikattu events were held across Tamil Nadu in protest of the ban,[70] and hundreds of participants were detained by police in response.

[71][72] The Supreme Court has agreed to delay its verdict on jallikattu for a week following the centre's request that doing so would avoid unrest.

Due to these protests, on 21 January 2017, the governor of Tamil Nadu issued a new ordinance that authorized the continuation of jallikattu events.

[73] On 23 January 2017 the Tamil Nadu legislature passed a bipartisan bill, with the accession of the Prime Minister, exempting jallikattu from the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act (1960).

|

|

Nationwide ban on bullfighting |

|

Nationwide ban on bullfighting, but some designated local traditions exempted |

|

|

Some subnational bans on bullfighting |

|

Bullfighting without killing bulls in the ring legal (Portuguese style or 'bloodless') |

|

|

Bullfighting with killing bulls in the ring legal (Spanish style) |

|

No data |