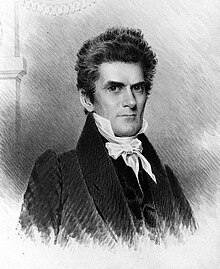

James B. Longacre

He portrayed the leading men of his day; support from some of them, such as South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun, led to his appointment as chief engraver after the death of Christian Gobrecht in 1844.

Bradford's Encyclopedia in 1820; an engraving of General Andrew Jackson by Longacre based on a portrait by Thomas Sully achieved wide sales.

He was on the point of launching this project, having invested $1,000 of his own money (equal to $30,520 today) in preparation, when he learned that James Herring of New York City was planning a similar series.

Among those who hoped for appointment were Philadelphia banknote engraver Charles Welsh, and Allen Leonard, who had modeled the Mint's medal for former president John Quincy Adams.

"[9] Longacre was commissioned by President Tyler on September 16, 1844;[5] his was a recess appointment as the post of chief engraver required Senate confirmation, and that body was not then sitting.

[10] According to numismatist David Lange, Longacre was glad to get the position because engravers were receiving less work due to the advent of daguerrotype photography.

[5][12] Peale controlled access to dies and materials, and was close to Director Patterson; the two men later proved to have been skimming metal from bullion deposits.

[13][14][15] Walter Breen, in his comprehensive volume on U.S. coins, suggests that Patterson resented Longacre because of the engraver's sponsorship by Calhoun, whom the director disliked as a southerner.

Gobrecht had redesigned every denomination of U.S. coinage between 1835 and 1842, and his successor had time to learn arts necessary for coin production that he had not needed as a maker of print engravings.

[17] Patterson wrote in August 1845 to Treasury Secretary Robert J. Walker that Longacre "is a gentleman of excellent character, highly regarded in this community, and has acquired some celebrity as an engraver of copper; but he is not a Die-Sinker.

"[18] By December of that year, the Mint director had written to Walker in praise of Longacre, stating that the engraver had "more taste and judgment in making devices for an improved coinage here than have been exhibited by any of his predecessors.

By then, Patterson had come to desire Longacre's departure as he was deemed a threat to Peale's medal business, and opposed new coins which would require the chief engraver's skills.

[16] According to Richard Snow in his book on Flying Eagle and Indian Head cents, "having an ethical chief engraver threatened their sideline.

Longacre proceeded with work on the double eagle through late 1849, and described the obstacles set in his path by Peale: The plan of operation selected for me was to have an electrotype mould made from my model, in copper, to serve as a pattern for a cast in iron.

[21] When Longacre completed the double eagle dies, they were rejected by Peale, who stated that the design was engraved too deeply to fully impress the coin, and the pieces would not stack properly.

[22] Peale complained to Patterson, who wrote to Treasury Secretary William M. Meredith asking for Longacre's removal on December 25, 1849, on the ground he could not make proper dies.

In a note found among his papers, Longacre wrote that his task was to make the coin as easy as possible to distinguish from the quarter eagle, which at $2.50 was close in value.

[34] At the time, a female Native American was often used to represent America in art, and a depiction of Liberty as an Indian princess was in accord with contemporary practices.

[35] The chief engraver wrote to Mint Director Snowden that the three-dollar piece, which went into production in 1854, was the first time he had been allowed artistic freedom in designing a coin.

[44] By numismatic legend, Longacre's Indian Head cent design was based on the features of his daughter Sarah; the tale runs that she was at the Philadelphia Mint one day when she tried on the headdress of one of a number of Native Americans who were visiting and her father sketched her.

These tales were apparently extant at the time, as Snowden, in writing to Treasury Secretary Howell Cobb in November 1858, denied that the coin was based "on any human features in the Longacre family".

The act which authorized the bronze cent also issued a two-cent piece; Longacre furnished a design, which Lange calls a "particularly attractive composition" with arrows and a laurel wreath flanking a shield.

[50][51] However, art historian Cornelius Vermeule stated that elements of the design "need only flanking cannon to be the consummate expressions of Civil War heraldry.

[50] Nickel had been removed from the cent over the objection of Pennsylvania industrialist Joseph Wharton, who had large interests in the metal; his congressman, Thaddeus Stevens, had fought against the act.

Longacre furnished a head of Liberty for the coin resembling his other depictions of the goddess which he had made in the past 16 years; for the reverse he used the "laurel" wreath from the 1859 cent surrounding the Roman numeral III borrowed from the silver three-cent piece.

Mint Assayer William DuBois wrote to Longacre, "it is truly pleasing to see a man pass the life of three score and ten and yet be able to produce the same artistic works as in earlier days.

The Andrew Johnson administration was happy to oblige; Treasury Secretary Hugh McCulloch gave the Chileans a letter of introduction to Longacre in Philadelphia.

McCulloch was initially agreeable, but Mint Director Pollock raised objection on the ground that government property should not be used to enable private gain.

The project was abandoned when it became clear the base-metal dime would be too large to be effectively struck in the tough copper-nickel alloy, but Longacre prepared a number of half dollar-size patterns.

In 1970, art historian Cornelius Vermeule, in his volume on U.S. coins, viewed Longacre and his works less favorably, "uniform in their dullness, lack of inspiration, and even quaintness, Longacre's contributions to patterns and regular coinage were a decided step backwards from the art of [Thomas] Sully, [Titian] Peale, [Robert] Hughes, and Gobrecht" and "whatever his previous qualities as an engraver of portraits, he seems not to have brought much imagination to his important post at the Philadelphia Mint.