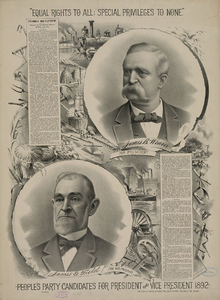

James B. Weaver

He joined the Republicans, opposed slavery, and served as an officer in the Union army during the civil war, but after 1876 he switched to the Greenbacks, then the Populists, and finally the Democrats.

After serving in the Union Army in the American Civil War, Weaver returned to Iowa and worked for the election of Republican candidates.

[6] Two years later, Weaver interrupted his legal career to accompany another brother-in-law, Dr. Calvin Phelps, on a cattle drive overland from Bloomfield to Sacramento, California.

[19] The 2nd Iowa, commanded by Colonel Samuel Ryan Curtis, a former Congressman, was ordered to Missouri in June 1861 to secure railroad lines in that border state.

[22] Weaver's first chance at action came in February 1862, when the 2nd Iowa joined Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant's army outside the Confederate Fort Donelson in Tennessee.

[31] They rejoined the action at the Battle of Resaca, a part of the Atlanta Campaign, then continued with Major General William Tecumseh Sherman's march through Georgia to the sea in 1864.

[31] On October 12th 1864, he would be selected to lead a local militia in Davis County after it was reported that Confederate partisans were actively raiding the area.

[38] Membership in the Methodist church coincided with Weaver's interest in the growing movement for prohibition of the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages.

[49] The Specie Payment Resumption Act, passed in 1875, ordered that greenbacks be gradually withdrawn and replaced with gold-backed currency beginning in 1879.

[54] The gubernatorial nominee, however, was John H. Gear, an opponent of Prohibition who had worked to defeat Weaver in his quest for the governorship two years earlier.

[57] Since the start of the Civil War, Democrats had been in the minority across Iowa; electoral fusion with Greenbackers represented their best chance to get their candidates into office.

[61] Although the House was closely divided, neither major party included the Greenbackers in their caucus, leaving them few committee assignments and little input on legislation.

[66] The proposed resolution would never be allowed to emerge from committees dominated by Democrats and Republicans, so Weaver planned to introduce it directly to the whole House for debate, as members were permitted to do every Monday.

[66] Rather than debate a proposition that would expose the monetary divide in the Democratic Party, Speaker Samuel J. Randall refused to recognize Weaver when he rose to propose the resolution.

[68] By 1879, the Greenback coalition had divided, with the faction most prominent in the South and West, led by Marcus M. "Brick" Pomeroy, splitting from the main party.

Chambers of Texas for vice president, but also sent a delegation to the National Greenback convention in Chicago that June, with an eye toward reuniting the party.

[84] Cutts died before taking office, and the Republicans offered to let Weaver run unopposed in the special election if he rejoined their party; he declined, and John C. Cook, a Democrat, won the seat.

[96] The bill died in committee, but Weaver reintroduced it in February 1886 and gave a speech calling for the Indian reservations to be broken up into homesteads for individual Natives and the remaining land to be open to white settlement.

[97] The Committee on Territories again rejected Weaver's bill, but approved a compromise measure that opened the Unassigned Lands, Cherokee Outlet, and Neutral Strip to settlement.

[101] In the lame-duck session of 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Act, which allowed the president to terminate tribal governments, and broke up Indian reservations into homesteads for individual natives.

[100] Although the Five Civilized Tribes were exempt from the Act, the spirit of the law encouraged Weaver and the Boomers to continue their own efforts to open western Indian Territory to white settlement.

[110] Weaver and his wife moved their household in 1890 from Bloomfield to Colfax, near Des Moines, as the former Congressman took up more active management of the Iowa Tribune.

[119] The platform adopted in Omaha was ambitious for its time, calling for a graduated income tax, public ownership of the railroads, telegraph, and telephone systems, government-issued currency, and the unlimited coinage of silver (the idea that the United States would buy as much silver as miners could sell the government and strike it into coins) at a favorable 16-to-1 ratio with gold.

[121] The Republicans nominated Harrison for re-election, and the Democrats put forward ex-President Cleveland; as in 1880, Weaver was confident of a good showing for the new party against their opponents.

[130] Weaver's performance was better than that of any third-party candidate since the Civil War,[e] as he won over a million votes – 8.5 percent of the total cast nationwide.

[134] After the election he attended a meeting of the American Bimetallic League, a pro-silver group, and gave speeches advocating an inflationist monetary policy.

[139] During the election, Weaver became friendly with William Jennings Bryan, a Democratic Congressman from Nebraska and a charismatic supporter of free silver.

[146] In 1900 Weaver attended a convention of fusionist Populists in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, the party having split on the issue of cooperation with the Democrats.

[147] The following year, Weaver was elected to office for the last time as the mayor of his hometown, Colfax, Iowa, after defeating Republican P. H. Cragen and served in that position until 1903.

[148][149] The Republican Party's popularity after the victory in the Spanish–American War led Weaver, for the first time, to doubt that populist values would eventually prevail.