James Planché

Over a period of approximately 60 years he wrote, adapted, or collaborated on 176 plays in a wide range of genres including extravaganza, farce, comedy, burletta, melodrama and opera.

[1] Jacques Planché was a moderately prosperous watchmaker, a trade he had learned in Geneva, and was personally known to King George III.

"[4] In 1808 he was apprenticed to a French landscape painter, Monsieur de Court, where he studied perspective and geometry, which would later help him in his theatre endeavours.

The manuscript of one of these early plays, Amoroso, King of Little Britain, was by chance seen by the comic actor John Pritt Harley, who, recognising its potential, brought about (and acted in)[6] its performance at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.

She wrote The Welsh Girl for the Olympic Theatre shortly after its opening in 1831 and, emboldened by its successful reception, continued to write for the stage.

Among her more successful plays were A Handsome Husband and A Pleasant Neighbour, both at the Olympic, and The Sledge Driver and The Ransom, both produced at the Haymarket Theatre.

Taking after her father in terms of writing output, Matilda Mackarness produced an average of one book a year until her death, most of them under her married name.

The play was a success and Harley, along with Stephen Kemble and Robert William Elliston, encouraged Planché to take up play-writing full-time.

[1] In 1826 he wrote the libretto for another opera, Oberon, or the Elf-King's Oath, the final work of composer Carl Maria von Weber, who died a few months after its completion.

Mendelssohn originally approved of Planché's choice of topic, Edward III's siege of Calais in the Hundred Years War, and responded positively to the first two acts of the libretto.

He observed to Charles Kemble, the manager of Covent Garden, that "while a thousand pounds were frequently lavished upon a Christmas pantomime or an Easter spectacle, the plays of Shakespeare were put upon the stage with makeshift scenery, and, at the best, a new dress or two for the principal characters".

The research involved sparked Planché's latent antiquarian interests; these came to occupy an increasing amount of his time later in life.

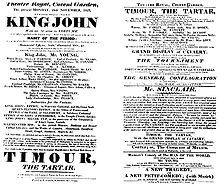

[20] Despite the actors' reservations, King John was a success and led to a number of similarly costumed Shakespeare productions by Kemble and Planché (Henry IV, Part I, As You Like It, Othello, Cymbeline, Julius Caesar).

Planché also wrote a number of plays or adaptations which were staged with historically accurate costumes (Cortez, The Woman Never Vext, The Merchant's Wedding, Charles XII, The Partisans, The Brigand Chief, and Hofer).

[23] In 1832 Edward Bulwer-Lytton, a novelist and MP, was successful in getting a select committee set up to consider dramatic copyright, as well as theatrical censorship and the monopoly of the patent theatres on drama.

[20] Olympic Revels was Planché's first example of "that form of travestie which is commonly described as 'classical'—which deals with the characteristics and adventures of gods and goddesses, heroes and heroines, of the Greek and Latin mythology and fable", a genre of which he was later credited as originator.

Feeling the need to do something different, Planché turned to a translation of the féerie folie (French: fairy tale) Riquet à la Houppe, which he had written some years earlier.

[29] Planché's fascination with her work led the press to refer to him as Madame d'Aulnoy's "preux chevalier" (French: devoted knight) and similar epithets.

[32] Planché's scholarly approach was exhibited in this area as well; he "translated two volumes of fairy tales by Mme D'Aulnoy, Perrault, and others, which were for the first time given in their integrity with biographical and historical notes and dissertations.

[12] As an example of the style of these works, Mr Buckstone's Voyage Round the Globe (1854), which played at the Haymarket Theatre, includes the words: "To the West, to the West, to the land of the free" – Which means those that happen white people to be – "Where a man is a man" – if his skin isn't black – If it is, he's a nigger, to sell or to whack ...[35] Planché semi-retired from the theatre in 1852 and went to live in Kent with his younger daughter (although he returned to London two years later on his appointment as Rouge Croix Pursuivant).

[1] Planché's research to determine historically accurate costume for the 1823 production of King John led to his developing a strong interest in the subject.

When he published his first major work in 1834, History of British Costume from the Earliest Period to the Close of the 18th Century, Planché described it as "the result of ten years' diligent devotion to its study of every leisure hour left me by my professional engagements".

[39] Prior to this Planché had published his costume designs for King John and the other Shakespeare plays, with "biographical, critical and explanatory notices".

However, he became dissatisfied with its management, complaining of "the lethargy into which the Society of Antiquaries had fallen, the dreariness of its meetings, the want of interest in its communications and the reluctance of its council to listen to any suggestions for its improvement".

In 1857 Planché was invited to arrange the collection of armour formerly belonging to his friend Sir Samuel Meyrick[41] for the Art Treasures Exhibition in Manchester, a task which he repeated in South Kensington in 1868.

[43] In 1872 he published his autobiography, a two-volume work entitled The Recollections and Reflections of J. R. Planché (Somerset Herald): a professional biography, containing many anecdotes of his life in the theatre.

His obituary in the Journal of the British Archaeological Association mentions in passing such topics as the following: Naval uniforms of Great Britain, early armorial bearings, processional weapons, horn-shaped headdresses of the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the clarion, the Stanley crest, ancient and medieval tapestries, armorials of Ferres and Peverel, the Cokayne monuments at Ashbourne, the tilting and other helmets, the family of Giffard, the Earls of Strigul (the Lords of Chepstow), relics of Charles I, the Earls and Dukes of Somerset, the statuary of the west front of Wells Cathedral, various effigies, brasses and portraits, the first Earl of Norfolk, the family of Fettiplace,[44] monuments in Shrewsbury Abbey, the Neville monuments, the Earls of Sussex, of Gloucester and of Hereford, and the Fairford windows.

As indicated by the subtitle, Planché was concerned with verifiable facts, as opposed to the unfounded theories perpetuated by many earlier heraldic writers.

[1] Planché also participated in state ceremonial within England; in 1856 he and other officers of arms proclaimed peace following the conclusion of the Crimean War.

He also left another heraldic legacy; Ursula Cull, the wife of future Garter King of Arms Sir George Bellew, was a descendant of Planché's daughter Matilda.