Jane Cobden

She remained committed throughout her life to the "Cobdenite" issues of land reform, peace, and social justice, and was a consistent advocate for Irish independence from Britain.

After her marriage to the publisher Thomas Fisher Unwin in 1892, Jane Cobden extended her range of interests into the international field, in particular advancing the rights of the indigenous populations within colonial territories.

[9] Because of his many absences from home, on parliamentary and other business, Richard Cobden was a somewhat remote figure to his daughters, although his letters indicate that he felt warmly towards them and that he wished to direct their political education.

Both parents impressed on the girls their responsibilities for the poor in the local community; Jane Cobden's 1864 diary records visits to homes and workhouses.

[12] After their father's death Jane and Anne attended Warrington Lodge school in Maida Hill but, following a disagreement the nature of which is unclear, both were removed from the school—"thrown on my hands", their mother complained.

[13] In this difficult time, Catherine did not withdraw into seclusion; in 1866 she supervised the re-publication of her husband's Political Writings,[12] and in the same year became one of the 1,499 signatories to the "Ladies Petition", an event that the historian Sophia Van Wingerden marks as the beginning of the organised women's suffrage movement.

The ménage proved unsatisfactory; Ellen, Jane and Anne were now displaying considerable independence of spirit, and differences of opinion arose between mother and daughters.

[15] In South Kensington, Ellen, Jane and Anne, often joined by Kate, established a sisterhood determined both to preserve Richard Cobden's memory and works and to uphold his principles and radical causes by actions of their own.

In London, she and her sisters extended their range of acquaintances into literary and artistic circles; among their new friends were the writer George MacDonald and the Pre-Raphaelites William and Jane Morris and Edward Burne-Jones.

Anne married Thomas Sanderson in 1882; inspired by her friendships within the Morris circle, her interests turned towards arts and crafts and eventually to socialism.

[21] The National Society's general stance was cautious; it avoided close identification with political parties, and for this reason would not accept affiliation from branches of the Women's Liberal Federation.

[22] This, and its policy of excluding married women from any extension of the franchise, led to a split in 1888, with the formation of a breakaway "Central National Society" (CNS).

[24] In 1848, Richard Cobden had written: "Almost every crime and outrage in Ireland is connected with the occupation or ownership of land ... if I had the power, I would always make the proprietors of the soil resident, by breaking up the large properties.

In a letter to The Times,[27] Jane and her associates cited one particular case—that of the Ryan family of Cloughbready in County Tipperary—to illustrate the British government's harshness towards even the most vulnerable of individuals.

[28] Jane was in contact with Irish Land League leaders, including John Dillon and William O'Brien, and lobbied for the release of the latter after his imprisonment under the Protection of Person and Property Act 1881.

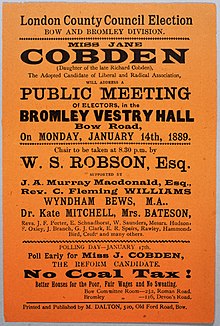

[33] Cobden's campaign in Bow and Bromley was organised with considerable enthusiasm and efficiency by the 29-year-old George Lansbury, then a Radical Liberal, later a socialist and eventually leader of the Labour Party.

[34] Both Cobden and Sandhurst were victorious in the elections on 19 January 1889; they were joined by Emma Cons, whom the Progressive majority on the council selected to serve as an alderman.

[35] Even so, her position on the council remained precarious, particularly after an attempt in parliament to legalise women's rights to serve as county councillors gained little support.

After a further parliamentary attempt to resolve the situation failed, she sat out the remaining months of her term as a councillor in silence, neither speaking nor voting, and did not seek re-election in the 1892 county elections.

Schneer also remarks that this "pioneering political venture of British feminism ... provides at once an anticipation of, and a direct contrast to, the militant suffragism of the Edwardian era".

[32][39] In 1892, at the age of 41, Cobden married Thomas Fisher Unwin, an avant-garde publisher whose list included works by Henrik Ibsen, Friedrich Nietzsche, H. G. Wells and the young Somerset Maugham.

[41] In 1900 she accepted the presidency of the Brighton Women's Liberal Association,[42] and in the same year wrote an extended tract, The Recent Development of Violence in our Midst, published by the Stop-the-War Committee.

[44] When the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) began its militant campaign in 1905, Cobden refrained from participation in illegal actions, although she spoke out for her sister when Anne became one of the first suffragists to be sent to prison, after a demonstration outside Parliament in October 1906.

[49] In 1904, Richard Cobden's centenary year, she published The Hungry Forties, described by Anthony Howe in a biographical article as "an evocative and brilliantly successful tract".

She supported Solomon Plaatje's campaign against the segregationist Natives' Land Act of 1913, a stance that led, in 1917, to her removal from the committee of the Anti-Slavery Society.

With the help of the writer and journalist Francis Wrigley Hirst and others, the house became a conference and education centre for pursuing the traditional Cobdenite causes of free trade, peace and goodwill.

[2] In old age she lived quietly at Oatscroft, her home near Dunford House, and following her husband's death in 1935 made few interventions in public life.

[1] During the 1930s, under Hirst's direction, Dunford House continued to preach what Howe describes as "the pure milk of the Cobdenian faith": the conviction that in Britain and in continental Europe, peace and prosperity would develop from individual ownership of the soil.

[1] In an essay on the Cobden sisterhood, the feminist historian Sarah Richardson remarks on the different paths chosen by the sisters by which to take their father's legacy forward: "Jane's activities showed that it was still possible to follow a radical agenda within the aegis of Liberalism".

Richardson indicates that the main collective achievement of Jane and her sisters was to ensure that the Cobden name, with its radical and progressive associations, survived well into the 20th century.