Constitution of Japan

Written primarily by American civilian officials during the occupation of Japan after World War II, it was adopted on 3 November 1946 and came into effect on 3 May 1947, succeeding the Meiji Constitution of 1889.

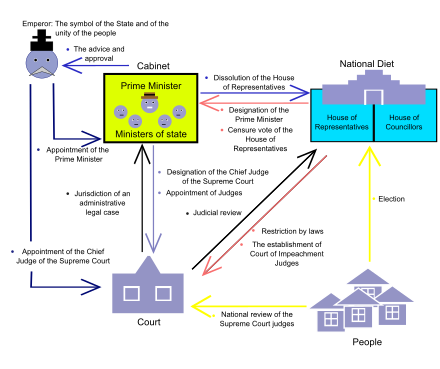

It is based on the principles of popular sovereignty, with the Emperor of Japan as the symbol of the state; pacifism and the renunciation of war; and individual rights.

[8][9] The constitution provides for a parliamentary system and three branches of government, with the National Diet (legislative), Cabinet led by a Prime Minister (executive), and Supreme Court (judicial) as the highest bodies of power.

It guarantees individual rights, including legal equality; freedom of assembly, association, and speech; due process; and fair trial.

On 26 July 1945, shortly before the end of World War II, Allied leaders of the United States (President Harry S. Truman), the United Kingdom (Prime Minister Winston Churchill), and the Republic of China (President Chiang Kai-shek) issued the Potsdam Declaration.

In addition, "The occupying forces of the Allies shall be withdrawn from Japan as soon as these objectives have been accomplished and there has been established in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people a peacefully inclined and responsible government" (Section 12).

The Japanese government, Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki's administration and Emperor Hirohito accepted the conditions of the Potsdam Declaration, which necessitates amendments to its Constitution after the surrender.

[13] The wording of the Potsdam Declaration—"The Japanese Government shall remove all obstacles ..."—and the initial post-surrender measures taken by MacArthur, suggest that neither he nor his superiors in Washington intended to impose a new political system on Japan unilaterally.

Emperor Hirohito, Prime Minister Kijūrō Shidehara, and most of the cabinet members were extremely reluctant to take the drastic step of replacing the 1889 Meiji Constitution with a more liberal document.

In other words, GHQ regarded the Emperor Hirohito not as a war criminal parallel to Hitler and Mussolini but as one governance mechanism.

Although the GHQ later denied this fact, citing a mistake by the Japanese interpreter, diplomatic documents between Japan and the U.S. state that "the Constitution must be amended to fully incorporate liberal elements".

However, this conflict ended with Konoe being nominated as a candidate for Class A war criminal due to domestic and international criticism.

In late 1945, Shidehara appointed Jōji Matsumoto, state minister without portfolio, head of a blue-ribbon committee of Constitutional scholars to suggest revisions.

The Matsumoto Committee was composed of the authorities of the Japanese law academia, including Tatsuki Minobe (美濃部達吉), and the first general meeting was held on 27 October 1945.

An additional reason for this was that on 24 January 1946, Prime Minister Shidehara had suggested to MacArthur that the new Constitution should contain an article renouncing war.

[21] Much of the drafting was done by two senior army officers with law degrees: Milo Rowell and Courtney Whitney, although others chosen by MacArthur had a large say in the document.

Kenzo Yanagi [24] mentioned the memorandum of Courtney Whitney, who was the director of the Civil Affairs Bureau of the General Headquarters, on 1 February 1946 as a reason for the attitude change.

Although the reason is not clear, this addition has led to the interpretation of the Constitution as allowing the retention of force when factors other than the purpose of the preceding paragraph arise.

2) In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained.

[26][27] The MacArthur draft, which proposed a unicameral legislature, was changed at the insistence of the Japanese to allow a bicameral one, with both houses being elected.

These included the constitution's most distinctive features: the symbolic role of the Emperor, the prominence of guarantees of civil and human rights, and the renunciation of war.

[citation needed] Yet in late 1945 and 1946, there was much public discussion on constitutional reform, and the MacArthur draft was apparently greatly influenced by the ideas of certain Japanese liberals.

Amendments require approval by two-thirds of the members of both houses of the National Diet before they can be presented to the people in a referendum (Article 96).

Yasuhiro Nakasone, a strong advocate of constitutional revision during much of his political career, for example, downplayed the issue while serving as prime minister between 1982 and 1987.

The edict states: I rejoice that the foundation for the construction of a new Japan has been laid according to the will of the Japanese people, and hereby sanction and promulgate the amendments of the Imperial Japanese Constitution effected following the consultation with the Privy Council and the decision of the Imperial Diet made in accordance with Article 73 of the said Constitution.

The constitution asserts that the Emperor is merely a symbol of the state, and that he derives "his position from the will of the people with whom resides sovereign power" (Article 1).

In particular Article 97 states that: the fundamental human rights by this Constitution guaranteed to the people of Japan are fruits of the age-old struggle of man to be free; they have survived the many exacting tests for durability and are conferred upon this and future generations in trust, to be held for all time inviolate.Under the constitution, the Emperor is "the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people".

Under Article 9, "the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes".

[36] Various political groups have called for either revising or abolishing the restrictions of Article 9 to permit collective defense efforts and strengthen Japan's military capabilities.

Thirty-one of its 103 articles are devoted to describing them in detail, reflecting the commitment to "respect for the fundamental human rights" of the Potsdam Declaration.