Japanese pottery and porcelain

Pottery and porcelain (陶磁器, tōjiki, also yakimono (焼きもの), or tōgei (陶芸)) is one of the oldest Japanese crafts and art forms, dating back to the Neolithic period.

Earthenwares were made as early as the Jōmon period (10,500–300 BC), giving Japan one of the oldest ceramic traditions in the world.

Japan is further distinguished by the unusual esteem that ceramics hold within its artistic tradition, owing to the enduring popularity of the tea ceremony.

In the early Edo period, the production of porcelain commenced in the Hizen-Arita region of Kyushu, employing techniques imported from Korea.

Japanese ceramic history records the names of numerous distinguished ceramists, and some were artist-potters, e.g. Hon'ami Kōetsu, Ninsei, Ogata Kenzan, and Aoki Mokubei.

[2] Since the 4th century AD, Japanese ceramics have often been influenced by the artistic sensibilities of neighbouring East Asian civilizations such as Chinese and Korean-style pottery.

Since the mid-17th century when Japan started to industrialize,[3] high-quality standard wares produced in factories became popular exports to Europe.

During the early Jōmon period in the 6th millennium BC typical coil-made ware appeared, decorated with hand-impressed rope patterns.

Five of these vessels from the southern Song dynasty are so highly valued that they were included by the government in the list of National Treasures of Japan (crafts: others).

From about 1720 Chinese and European kilns also began to imitate the Imari enamelled style at the lower end of the market, and by about 1740 the first period of Japanese export porcelain had all but ceased.

[16] Porcelain was also exported to China, much of which was resold by Chinese merchants to the other European "East Indies Companies" which were not allowed to trade in Japan itself.

It has been suggested that the choice of such items was mainly dictated by Chinese taste, which preferred Kakiemon to "Imari" wares, accounting for a conspicuous disparity in early European collections that can be reconstructed between Dutch ones and those of other countries, such as England, France and Germany.

In 1759 the dark red enamel pigment known as bengara became industrially available, leading to a reddish revival of the orange 1720 Ko-Imari style.

Among them, potter Nonomura Ninsei invented an opaque overglaze enamel and with temple patronage was able to refine many Japanese-style designs.

His disciple Ogata Kenzan invented an idiosyncratic arts-and-crafts style and took Kyōyaki (Kyoto ceramics) to new heights.

Aoki Mokubei, Ninami Dōhachi (both disciples of Okuda Eisen) and Eiraku Hozen expanded the repertory of Kyōyaki.

In the late 18th to early 19th century, white porcelain clay was discovered in other areas of Japan and was traded domestically, and potters were allowed to move more freely.

Seen in the West as distinctively Japanese, this style actually owed a lot to imported pigments and Western influences, and had been created with export in mind.

[24] Meizan used copper plates to create detailed designs and repeatedly transfer them to the pottery, sometimes decorating a single object with a thousand motifs.

[26] During this era, technical and artistic innovations turned porcelain into one of the most internationally successful Japanese decorative art forms.

[26] A lot of this is due to Makuzu Kōzan, known for Satsuma ware, who from the 1880s onwards introduced new technical sophistication to the decoration of porcelain, while committed to preserving traditional artistic values.

[31] He lived in Japan from 1909 to 1920 during the Taishō period and became the leading western interpreter of Japanese pottery and in turn influenced a number of artists abroad.

The kilns at Tamba, overlooking Kobe, continued to produce the daily wares used in the Tokugawa period, while adding modern shapes.

In Okinawa, the production of village ware continued under several leading masters, with Kinjo Jiro honored as a ningen kokuho (人間国宝, lit.

Artist potters experimented at the Kyoto and Tokyo arts universities to recreate traditional porcelain and its decorations under such ceramic teachers as Fujimoto Yoshimichi, a ningen kokuho.

British artist Lucie Rie (1902–1995) was influenced by Japanese pottery and Bernard Leach, and was also appreciated in Japan with a number of exhibitions.

[33] In contrast, by the end of the 1980s, many studio potters no longer worked at major or ancient kilns but were making classic wares in various parts of Japan.

A number of artists were engaged in reconstructing Chinese styles of decoration or glazes, especially the blue-green celadon and the watery-green qingbai.

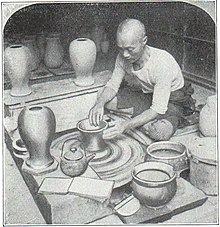

The preliminary steps are the same as for coil building, after which the rough form is lubricated with slip and shaped between the potter's hands as the wheel revolves.

Generally fashioned out of fast-growing bamboo or wood, these tools for shaping pottery have a natural feel that is highly appealing.