Japanese prisoners of war in World War II

[4][5] Western Allied governments and senior military commanders directed that Japanese POWs be treated in accordance with relevant international conventions.

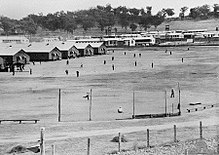

The prisoners taken by the Western Allies were held in generally good conditions in camps located in Australia, New Zealand, India and the United States.

[8] The relatively good treatment that prisoners in Japan received was used as a propaganda tool, exuding a sense of "chivalry" in comparison to the more barbaric perception of Asia that the Meiji government wished to avoid.

While Japan signed the 1929 Geneva Convention covering treatment of POWs, it did not ratify the agreement, claiming that surrender was contrary to the beliefs of Japanese soldiers.

This document sought to establish standards of behavior for Japanese troops and improve discipline and morale within the Army, and included a prohibition against being taken prisoner.

[13] The Japanese Government accompanied the Senjinkun's implementation with a propaganda campaign which celebrated people who had fought to the death rather than surrender during Japan's wars.

[14] While the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) did not issue a document equivalent to the Senjinkun, naval personnel were expected to exhibit similar behavior and not surrender.

While scholars disagree over whether the Senjinkun was legally binding on Japanese soldiers, the document reflected Japan's societal norms and had great force over both military personnel and civilians.

[15] The indoctrination of Japanese military personnel to have little respect for the act of surrendering led to conduct which Allied soldiers found deceptive.

Those who chose to surrender did so for a range of reasons including not believing that suicide was appropriate or lacking the will to commit the act, bitterness towards officers, and Allied propaganda promising good treatment.

[21] During the later years of the war Japanese troops' morale deteriorated as a result of Allied victories, leading to an increase in the number who were prepared to surrender or desert.

[22] During the Battle of Okinawa, 11,250 Japanese military personnel (including 3,581 unarmed labourers) surrendered between April and July 1945, representing 12 percent of the force deployed for the defense of the island.

Many of these men were recently conscripted members of Boeitai home guard units who had not received the same indoctrination as regular Army personnel, but substantial numbers of IJA soldiers also surrendered.

[24] Hoyt in "Japan’s war: the great Pacific conflict" argues that the Allied practice of taking bones from Japanese corpses home as souvenirs was exploited by Japanese propaganda very effectively, and "contributed to a preference to death over surrender and occupation, shown, for example, in the mass civilian suicides on Saipan and Okinawa after the Allied landings".

[24] The causes of the phenomenon that Japanese often continued to fight even in hopeless situations has been traced to a combination of Shinto, messhi hōkō (self-sacrifice for the sake of group), and Bushido.

[33] Despite the attitudes of combat troops and nature of the fighting, Allied militaries made systematic efforts to take Japanese prisoners throughout the war.

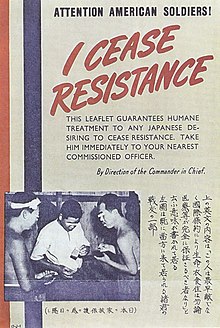

[34] Allied forces mounted an extensive psychological warfare campaign against their Japanese opponents to lower their morale and encourage surrender.

[37] As a result, from May 1944, senior US Army commanders authorized and endorsed educational programs which aimed to change the attitudes of front line troops.

Because they had been indoctrinated to believe that by surrendering they had broken all ties with Japan, many captured personnel provided their interrogators with information on the Japanese military.

The prisoners appreciated the opportunity to converse with Japanese-speaking Americans and felt that the food, clothing and medical treatment they were provided with meant that they owed favours to their captors.

[55] Force was not used in interrogations at any level, though on one occasion headquarters personnel of the US 40th Infantry Division debated, but ultimately decided against, administering sodium penthanol to a senior non-commissioned officer.

[56] Some Japanese POWs also played an important role in helping the Allied militaries develop propaganda and politically indoctrinate their fellow prisoners.

[58] POWs also provided advice on the wording for propaganda leaflets which were dropped on Japanese cities by heavy bombers in the final months of the war.

The United States provided these countries with aid through the Lend Lease program to cover the costs of maintaining the prisoners, and retained responsibility for repatriating the men to Japan at the end of the war.

[64] Prisoners who were thought to possess significant technical or strategic information were brought to specialist intelligence-gathering facilities at Fort Hunt, Virginia or Camp Tracy, California.

This tactic was initially rejected by General Douglas MacArthur when it was proposed to him in mid-1943 on the grounds that it violated the Hague and Geneva Conventions, and the fear of being identified after surrendering could harden Japanese resistance.

While this measure was successful in avoiding unrest, it led to hostility between those who surrendered before and after the end of the war and denied prisoners of the Soviets POW status.

Tens of thousands of Japanese prisoners captured by Chinese communists were serving in their military forces in August 1946 and more than 60,000 were believed to still be held in Communist-controlled areas as late as April 1949.

[28] Unlike the prisoners held by China or the western Allies, these men were treated harshly by their captors, and over 60,000 died by Russian sources.

[83] Japanese POWs were forced to undertake hard labour and were held in primitive conditions with inadequate food and medical treatments.