Japanese swordsmithing

Japanese swordsmithing is the labour-intensive bladesmithing process developed in Japan beginning in the sixth century for forging traditionally made bladed weapons (nihonto)[1][2] including katana, wakizashi, tantō, yari, naginata, nagamaki, tachi, nodachi, ōdachi, kodachi, and ya (arrow).

Because the charcoal cannot exceed the melting point of iron, the steel is not able to become fully molten, and this allows both high and low carbon material to be created and separated once cooled.

[3] A single kera batch can typically be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, making it many times more expensive than modern steels.

From the Middle Ages, as the size of furnaces became larger and the underground structure became more complicated, it became possible to produce a large amount of steel of higher quality, and in the Edo period, the underground structure, the blowing method, and the building were further improved to complete tatara steelmaking process using the same method as modern tatara steelmaking.

[5][6][7][8] Currently, tamahagane is only made three or four times a year by The Society for Preservation of Japanese Art Swords and Hitachi Metals[9] during winter in a wood building and is only sold to master swordsmiths.

The forging of a Japanese blade typically took many days or weeks and was considered a sacred art, traditionally accompanied by a large panoply of Shinto religious rituals.

The process of folding metal to improve strength and remove impurities is frequently attributed to specific Japanese smiths in legends.

The folding removes impurities and helps even out the carbon content, while the alternating layers combine hardness with ductility to greatly enhance the toughness.

At around 1,650 °F (900 °C), the heat and water from the clay promote the formation of a wustite layer, which is a type of iron oxide formed in the absence of oxygen.

[17][13][19] Through the loss of impurities, slag, and iron in the form of sparks during the hammering, by the end of forging the steel may be reduced to as little as 1/10 of its initial weight.

[20] The vast majority of modern katana and wakizashi are the maru type (sometimes also called muku) which is the most basic, with the entire sword being composed of a single steel.

[12] Sometimes the edge-steel is "drawn out" (hammered into a bar), bent into a U-shaped trough, and the very soft core steel is inserted into the harder piece.

The term kenukigata is derived from the fact that the central part of tang is hollowed out in the shape of a tool to pluck hair (kenuki).

[24][26] In the Muromachi period, battles were mostly fought on foot, and the samurai equipped with swords changed from the tachi to the light katana because many mobilized peasants were armed with spears and matchlock guns.

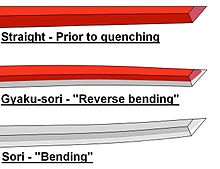

However, the edge cannot contract fully before the martensite forms, because the rest of the sword remains hot and in a thermally expanded state.

The hamon is the visible outline of the yakiba (hardened portion) and is used as a factor to judge both the quality and beauty of the finished blade.

Separation of the various metals from the bloom was traditionally performed by breaking it apart with small hammers dropped from a certain height, and then examining the fractures, in a process similar to the modern Charpy impact test.

[36] Cyril Stanley Smith, a professor of metallurgical history from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, performed an analysis of four different swords, each from a different century, determining the composition of the surface of the blades:[37] In 1993, Jerzy Piaskowski performed an analysis of a katana of the kobuse type by cutting the sword in half and taking a cross section.

In one of the first metallurgical studies, Professor Kuni-ichi Tawara suggests that layers of high slag may have been added for practical as well as decorative reasons.

Like all trial-and-error, each swordsmith often attempted to produce an internal structure that was superior to swords of their predecessors, or even ones that were better than their own previous designs.

In later times, this effect was often imitated by partially mixing various metals like copper together with the steel, forming mokume (wood-eye) patterns, although this was unsuitable for the blade.

Different types of file markings are used, including horizontal, slanted, and checked, known as ichi-monji, ko-sujikai, sujikai, ō-sujikai, katte-agari, shinogi-kiri-sujikai, taka-no-ha, and gyaku-taka-no-ha.

It is this pressure fit for the most part that holds the hilt in place, while the mekugi pin serves as a secondary method and a safety.

Some other marks on the blade are aesthetic: signatures and dedications written in kanji and engravings depicting gods, dragons, or other acceptable beings, called horimono.

More importantly, inexperienced polishers can permanently ruin a blade by badly disrupting its geometry or wearing down too much steel, both of which effectively destroy the sword's monetary, historic, artistic, and functional value.

[citation needed] In Japanese, the scabbard for a katana is referred to as a saya, and the handguard piece, often intricately designed as an individual work of art—especially in later years of the Edo period—was called the tsuba.

Sword mountings vary in their exact nature depending on the era but consist of the same general idea, with the variation being in the components used and in the wrapping style.

The hand guard, or tsuba, on Japanese swords (except for certain 20th century sabers which emulate Western navies') is small and round, made of metal, and often very ornate.

[46] The metal used to make low-quality blades is mostly cheap stainless steel, and typically is much harder and more brittle than true katana.

[50] With a normal Rockwell hardness of 56 and up to 60, stainless steel is much harder than the back of a differentially hardened katana (HR50), and is therefore much more prone to breaking, especially when used to make long blades.