Jeffrey R. MacDonald

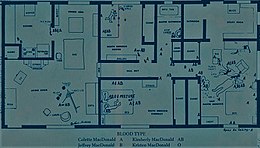

MacDonald has always proclaimed his innocence of the murders, which he claims were committed by four intruders—three male and one female—who had entered the unlocked rear door of his apartment at Fort Bragg, North Carolina,[2] and attacked him, his wife, and his children with instruments such as knives, clubs and ice picks.

The two formed a brief romantic relationship in the ninth grade, with MacDonald later recollecting they fell in love while holding hands on a balcony while watching the movie A Summer Place at the Rialto Theater in Patchogue.

The couple moved into a small one-bedroom apartment, with Colette committed to maintaining the household and raising their daughter as MacDonald focused on his studies, while also working a series of part-time jobs to assist with family finances.

Both daughters had developed distinctive personalities: Kimberley being markedly feminine, intelligent, and shy; Kristen a boisterous tomboy who would "run over and crack someone" if she observed her older sister being bullied by other children.

[31] The same month, Colette is known to have penned a letter to college acquaintances in which she described her life as "never [being] so normal or happy", adding she and her husband were content, that their baby son was due to be born in July, and her family would be complete.

"[53] During the struggle, his pajama top was pulled over his head to his wrists and he had used this bound garment to ward off thrusts from the ice pick although eventually, he was overcome by his assailants and knocked unconscious in the living room end of the hallway leading to the bedrooms.

These instruments were an Old Hickory kitchen knife, an ice pick, and a 31-inch long piece of lumber with two blue threads attached with blood; all three were quickly determined to have come from the MacDonald house, and all had been wiped clean of fingerprints.

Although MacDonald was trained in unarmed combat,[59] the living room where he had supposedly fought for his life against three armed assailants showed few signs of a struggle apart from a coffee table that had been knocked onto its side with a pile of magazines beneath the edge, and a flower plant that had fallen to the floor.

[67] By mid-March, the CID had obtained the results of forensic testing of the blood, hair, and fiber samples within 544 Castle Drive that contradicted MacDonald's accounts of his movements and further convinced investigators of his guilt.

As he retaliated by hitting her, first with his fists and then beating her with a piece of lumber, Kimberley, whose blood and brain serum were found in the doorway, may have walked in after hearing the commotion and was struck at least once on the head, possibly by accident.

[9] MacDonald then laid his torn pajama top over her dead body and repeatedly stabbed her in the chest with an ice pick, then discarded the weapons close to the back door of the property after wiping them clean of fingerprints.

Investigator Robert Shaw then questioned MacDonald as to the lack of disorder and damage within the household, and the lack of any motive, stating that in the investigators' experience, had four intruders embarked on a murderous frenzy within a small household, they would expect to encounter evidence such as "busted furniture and broken mirrors and bashed-in walls", but the only signs of the struggle were the top-heavy living room coffee table, which had not flipped over all the way in the midst of his struggle, and a flower pot beside the table with the plant upon the carpet and the pot standing upright.

[85][86] That same day, MacDonald penned a letter to Colette's mother and stepfather professing his innocence, emphasizing the Army would "never admit" their error, and speculating his wife's soul may hold "infinite patience and understanding" of his current legal predicament.

[90] Segal elicited several examples of incompetence from military police and responding personnel, including testimony revealing that an ambulance driver had stolen MacDonald's wallet from the living room,[91] and a pathologist who testified to having failed to obtain the children's fingerprints for comparison at the crime scene.

Sections of his testimony contradicted what he had informed investigators on April 6, including his claim on this occasion to have actually moved Colette's body, having found her "a little bit propped up against a chair" before he "just sort of laid her flat" on the floor.

This expert testified that the tests revealed an extraordinary absence of anxiety, depression, and anger in MacDonald with regard to the loss of his family, and that his report concluded he was "able to muster massive denial or repression" to such a degree that the "impact of the recent events in his life has been blunted".

[105] In December, MacDonald received an honorable discharge from the Army and initially returned to New York City, where he briefly worked as a doctor before relocating to Long Beach, California in July 1971[35][106] in an effort to "put the past" behind him and to distance himself from the "constant reminders" of his wife and daughters.

[128] A reporter who had covered the Article 32 hearing and who interviewed MacDonald after the charges were dropped also stated that, in his experience, individuals under the influence of LSD seldom become violent and that, by contrast, those who consume amphetamines frequently do.

Dupree justified this refusal by stating that, as MacDonald's attorneys had not entered an insanity plea for their client, he did not wish for the trial to be hindered by opinionated and contradictory psychiatric testimony from prosecution and defense witnesses.

[146] On the first day of the trial, Judge Dupree allowed the prosecution to admit into evidence the March 1970 copy of Esquire magazine, found in the MacDonald house, part of which contained the lengthy article relating to the Manson Family murders.

[150] A further piece of damaging evidence against MacDonald was an audio tape made of the April 6, 1970 interview by military investigators, which was played in the courtroom immediately after the jurors had returned from visiting the still-intact crime scene.

For example, he was unable to explain how the piece of lumber used as a weapon came from a mattress slat on Kimberley's bed, but claimed there "may have been" some wood in the utility room, later adding his insistence the club which had struck him across the head was "sort of smooth" and may have been a baseball bat as opposed to a wooden instrument.

Segal focused much of his closing argument upon the "campaign of persecution" his client had been subjected to by the legal system for almost a decade in an attempt to frame him for the murder of his family, describing the prosecution's case as a "house built on sand".

This appeal contended that, had Judge Dupree permitted this evidence, the jurors would have learned that all of the doctors hired by the defense, who had worked for the Army, or the government at Walter Reed Hospital, had concluded that MacDonald was psychologically incapable of committing such acts of violence.

[186] In September 2012, the district court conducted a formal evidentiary hearing regarding DNA evidence and statements relating to key witnesses who offered testimony indicating MacDonald's innocence.

[193] Shortly after MacDonald's initial release from prison in August 1980, his supporters hired a retired FBI Special Agent and private investigator named Ted Gunderson to assist in overturning his conviction.

Gunderson contacted Helena Stoeckley, who on this occasion confessed that she and five members of what she described as a "drug cult" had developed a deep grudge against MacDonald as he had "refused to treat heroin- and opium-addicted" patients.

[198] On January 12, 2006, MacDonald was granted leave to file a further appeal based upon a November 2005 affidavit of retired Deputy United States Marshal Jim Britt, who had served in this role during the trial.

[206] Furthermore, the book emphasizes the fact MacDonald worked extremely long hours in several medical employment roles in 1969 and 1970, and his extensive social and family commitments, resulted in his suffering from an increasing lack of sleep.

[230] James Blackburn, a lead prosecutor in the 1979 trial, later admitted that between 1990 and 1991 he had forged several court documents unrelated to the MacDonald case, and illegally wired money from his law firm's bank account.