Jesus Prayer

Pope John Paul II called Gregory Palamas a saint,[7] a great writer, and an authority on theology.

[8][9][10] He also spoke with appreciation of hesychasm as "that deep union of grace which Eastern theology likes to describe with the particularly powerful term theosis, 'divinization'",[11] and likened the meditative quality of the Jesus Prayer to that of the Catholic rosary.

[14] A formula similar to the standard form of the Jesus Prayer is found in a letter attributed to John Chrysostom, who died in AD 407.

[15] What may be the earliest explicit reference to the Jesus Prayer in a form that is similar to that used today is in Discourse on Abba Philimon from the Philokalia.

[6] The use of the Jesus Prayer according to the tradition of the Philokalia is the subject of the 19th century anonymous Russian spiritual classic The Way of a Pilgrim, also in the original form, without the addition of the words "a sinner".

Semi-Autonomous: The hesychastic practice of the Jesus Prayer is founded on the biblical view by which God's name is conceived as the place of his presence.

Thus, the most important means of a life consecrated to praying is the invoked name of God, as it is emphasized since the 5th century by the Thebaid anchorites, or by the later Athonite hesychasts.

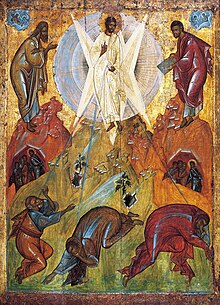

Incognoscibility is not conceived as agnosticism or refusal to know God, because the Eastern theology is not concerned with abstract concepts; it is contemplative, with a discourse on things above rational understanding.

[25][26] The Eastern Orthodox Church holds a non-juridical view of sin, by contrast to the satisfaction view of atonement for sin as articulated in the West, firstly[citation needed] by Anselm of Canterbury (as debt of honor)[need quotation to verify]) and Thomas Aquinas (as a moral debt).

[need quotation to verify] The terms used in the East are less legalistic (grace, punishment), and more medical (sickness, healing) with less exacting precision.

Repentance (Ancient Greek: μετάνοια, metanoia, "changing one's mind") is not remorse, justification, or punishment, but a continual enactment of one's freedom, deriving from renewed choice and leading to restoration (the return to man's original state).

The form of internal contemplation involving profound inner transformations affecting all the levels of the self is common to the traditions that posit the ontological value of personhood.

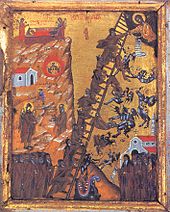

The aim of the Christian practicing it is not limited to attaining humility, love, or purification of sinful thoughts, but rather it is becoming holy and seeking union with God (theosis), which subsumes all the aforementioned virtues.

[32] Instead, as a hesychastic practice, it demands setting the mind apart from rational activities and ignoring the physical senses for the experiential knowledge of God.

[21][30] There are no fixed rules for those who pray, "the way there is no mechanical, physical or mental technique which can force God to show his presence" (Metropolitan Kallistos Ware).

[sentence fragment][34] Paul Evdokimov, a 20th-century Russian philosopher and theologian, writes[35] about beginner's way of praying: initially, the prayer is excited because the man is emotive and a flow of psychic contents is expressed.

In his view this condition comes, for the modern men, from the separation of the mind from the heart: "The prattle spreads the soul, while the silence is drawing it together."

They are to be seen as being purely informative, because the practice of the Prayer of the Heart is learned under personal spiritual guidance in Eastern Orthodoxy which emphasizes the perils of temptations when it is done on one's own.

Thus, Theophan the Recluse, a 19th-century Russian spiritual writer, talks about three stages:[21] Once this is achieved the Jesus Prayer is said to become "self-active" (αυτενεργούμενη).

They are the same path to theosis, more slenderly differentiated:[36] A number of different repetitive prayer formulas have been attested in the history of Eastern Orthodox monasticism: the Prayer of St. Ioannikios the Great (754–846): "My hope is the Father, my refuge is the Son, my shelter is the Holy Ghost, O Holy Trinity, Glory unto You", the repetitive use of which is described in his Life; or the more recent practice of Nikolaj Velimirović.

When the holy name is repeated often by a humbly attentive heart, the prayer is not lost by heaping up empty phrases, but holds fast to the word and "brings forth fruit with patience."