Jewish councils in Hungary

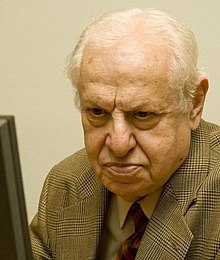

Samu Stern stated in one of his letters to Prime Minister Miklós Kállay in July 1943 that despite the anti-Semitic "Jewish laws" and regulations, the situation of Hungarian Jews was immeasurably better compared to the communities of neighboring countries, which were being threatened with physical annihilation.

[8] Following World War II, the Hungarian Jewish leadership was accused of concealing information about Nazi genocides and concentration camps from its members in the years before the German invasion of Hungary.

[12] Veszprémy argued, despite wartime censorship, many Hungarian articles dealt with certain events of the Holocaust (deportations, ghettos, pogroms and massacres) around German-occupied Europe and allied and client states (for instance, Romania, Slovakia and Croatia), even years before the German occupation.

Numerous contemporary diary entries from different social strata prove that the Jews knew about the Nazi genocides elsewhere in Europe, but did not want to believe them, as a result of a kind of mass psychosis.

[22] Samu Stern wrote in his memoirs in 1946 that "I considered it a cowardly, unmanly and irresponsible behavior, a selfish escape and running away, if I let my fellow believers down now, right now, when leadership is needed the most, when the sacrificial work of experienced and politically connected men could perhaps help them".

[25] In his memoirs written in 1947, Ernő Munkácsi divided the activity of the Jewish Council of Budapest into four parts; the first lasting from its formation on 20 March until the establishment of the Association of Hungarian Jews Provisional Executive Committee on 1 May.

Historians Gábor Kádár and Zoltán Vági maintained the periodization, arguing that the operation of the "second council" was legalized by the Hungarian authorities, while the Arrow Cross Party coup and the subsequent ghetto and siege created a new situation for its activity.

[27] On 21 March 1944, the Germans accepted Stern's list, establishing the Central Council of Hungarian Jews (Magyar Zsidók Központi Tanácsa), to which jurisdiction over the whole country (i.e. national Jewish affairs) had been assigned.

Upon the demands of Krumey and Wisliceny, another meeting was convened on 28 March, which was also attended by twenty-seven rabbis and leaders from the congregation districts in countryside, mostly Neolog, but also some Orthodox, after they were granted domestic travel permits by the German administration.

[37] In addition to the accusations, Veszprémy emphasized the importance of the Magyarországi Zsidók Lapja: the warnings (e.g. no smoking, regular wearing a yellow badge) were often about protecting lives, since even minor transgressions led to internment and ultimately deportation to Auschwitz.

[39] Overall, however, the Jewish councils had to function in complete isolation from each other from the very beginning, because the Jews were deprived of all means of communication (e.g. termination of telephone lines, mail censorship and travel ban) soon after the invasion of Hungary.

[8] In the second half of September 1944, now under the premiership of Géza Lakatos in a more optimistic situation, the Central Jewish Council attempted to contact the Hungarian Front, an illegal anti-fascist resistance network of banned parties and organizations.

This started on 20 October in collection camps all over Budapest (e.g. the KISOK sports field in Zugló, Tattersalls, the Dózsa György Street Synagogue, a brick factory in Óbuda, and the Józsefváros railway station).

[96] There were also supporters of the Zionist movement in the leaderships of some councils, for instance, in Kolozsvár (József Fischer), Székesfehérvár (Miklós Szegő), Nagyvárad (Sándor Leitner, a Mizrachi) and Kassa (Artúr Görög).

It was headed by timber merchant János Biringer, who, with the intention of establishing local Jewish councils, convened religious assemblies in Érsekújvár (today Nové Zámky, Slovakia) and Veszprém too.

Lipót Löw, a Neolog rabbi and member of the council in Szeged, recalled that they received a letter from the local SS official on 20 June, in which Zionist leader Ernő Szilágyi stated that he had a mandate that 3,000 Jews must be selected based on several criteria (relatives of prominent Jewish figures, among others).

In the Szolnok camp, council leaders Béla Schwartz of Kisújszállás, Sándor Szűcs of Füzesgyarmat and József Práger of Kiskunhalas selected those to be deported and the families of prominent people, military veterans, and labor servicemen enjoyed an advantage.

For instance, Zionist activist Mór Feldmann, head of the council in Miskolc sent a letter to the local anti-Semitic mayor László Szlávy on 1 May 1944, in which he pleaded for the rescue of 10,000 Jews in an extremely respectful, flattering tone.

Samu Kahan-Frankl claimed in 1964 during the Krumey Trial, an agreement was concluded with the Germans to save rural Jewish councils, who would have been transported by the last trains according to one of László Endre's instructions.

During the Kastner trial, Fülöp Freudiger stated that Eichmann, in exchange for substantial sums of money, promised that the first-degree relatives of all Jewish council members throughout Hungary would be exempt from deportation.

Around the same time, representatives of the Hungarian government – István Antal and Miklós Mester – and the Reformed and Evangelical churches – like Bishop László Ravasz – negotiated on the establishment of a ministerial subdivision dealing with Converts in the Ministry of Religion and Education.

The Christian Jewish Council was disestablished in the first days of the Arrow Cross Party coup, Sándor Török survived the siege of the capital at the mansion of former government minister Emil Nagy.

[136] The verification committee classified Munkácsi as unfit to hold a leadership position because he went into hiding following the Arrow Cross Party's takeover in October 1944, abandoning his community (however he tried unsuccessfully to return to work to the Jewish council in December).

Szabad Nép, the official newspaper of the Hungarian Communist Party (MKP) connected the amounts to the collaborative behavior of the defunct Jewish Council of Budapest, who had "only helped rich Jews".

[139] Lajos Gondos, head of the Jewish ghetto police in Simapuszta internment camp (Nyíregyháza) was sentenced to two-year imprisonment in the first instance in August 1946, but later he was acquitted by the National Council of People's Tribunals (NOT) in the same year.

[141] Simultaneously with the interrogations, the pro-Communist newspapers (e.g. Magyar Nemzet, Reggel, Szabad Szó, Ludas Matyi) launched a series of disparaging campaigns against Berend, calling him a "Nazi-puppet rabbi" and the "informant of the Gestapo".

According to the indictment, Berend was an informant of the gendarmes, the Arrow Cross Party and the Gestapo regarding the whereabouts of Jewish wealth and he also took part in a raid to the International Ghetto (Pozsonyi út) in January 1945.

Three leaders of the Budapest Jewish community, László Benedek, Lajos Stöckler, and Miksa Domonkos, as well as two additional "eyewitnesses" Pál Szalai and Károly Szabó were arrested and tortured by the State Protection Authority (ÁVH).

In her prelude, editor Ilona Benoschofsky, who was a former employee of the council's housing department, wrote that the Jewish leadership "carried out German orders without resistance and did not try to find the very small possibilities of escape".

[155] Braham, the most influential researcher of the Holocaust in Hungary, considered that Jewish councils in Europe became "involuntary accessories to German crimes", whose members, who intended to buy time to alleviate the suffering of the Jews, "were trapped into outright though unwitting collaboration".