Jewish diaspora

The Jewish diaspora in the second Temple period (516 BCE – 70 CE) was created from various factors, including through the creation of political and war refugees, enslavement, deportation, overpopulation, indebtedness, military employment, and opportunities in business, commerce, and agriculture.

This watershed moment, the elimination of the symbolic centre of Judaism and Jewish identity motivated many Jews to formulate a new self-definition and adjust their existence to the prospect of an indefinite period of displacement.

Diaspora has been a common phenomenon for many peoples since antiquity, but what is particular about the Jewish instance is the pronounced negative, religious, indeed metaphysical connotations traditionally attached to dispersion and exile (galut), two conditions which were conflated.

[10] The English term diaspora, which entered usage as late as 1876, and the Hebrew word galut though covering a similar semantic range, bear some distinct differences in connotation.

[26] After the overthrow of the Kingdom of Judah in 586 BCE by Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon (see Babylonian captivity) and the deportation of a considerable portion of its inhabitants to Mesopotamia, the Jews had two principal cultural centers: Babylonia and the land of Israel.

[30] Lester L. Grabbe asserted that the "alleged decree of Cyrus"[31] regarding Judah, "cannot be considered authentic", but that there was a "general policy of allowing deportees to return and to re-establish cult sites".

[32] Although most of the Jewish people during this period, especially the wealthy families, were to be found in Babylonia, the existence they led there, under the successive rulers of the Achaemenids, the Seleucids, the Parthians, and the Sassanians, was obscure and devoid of political influence.

[35][better source needed] Jews began settling in Cyrenaica (modern-day eastern Libya) around the third century BCE, during the rule of Ptolemy I of Egypt, who sent them to secure the region for his kingdom.

Soon, however, discord within the royal family and the growing disaffection of the pious towards rulers who no longer evinced any appreciation of the real aspirations of their subjects made the Jewish nation easy prey for the ambitions of the now increasingly autocratic and imperial Romans, the successors of the Seleucids.

Jews migrated to new Greek settlements that arose in the Eastern Mediterranean and former subject areas of the Persian Empire on the heels of Alexander the Great's conquests, spurred on by the opportunities they expected to find.

[38] The proportion of Jews in the diaspora in relation to the size of the nation as a whole increased steadily throughout the Hellenistic era and reached astonishing dimensions in the early Roman period, particularly in Alexandria.

It was not least for this reason that the Jewish people became a major political factor, especially since the Jews in the diaspora, notwithstanding strong cultural, social and religious tensions, remained firmly united with their homeland.

At the commencement of the reign of Caesar Augustus, there were over 7,000 Jews in Rome (though this is only the number that is said to have escorted the envoys who came to demand the deposition of Archelaus; compare: Bringmann: Klaus: Geschichte der Juden im Altertum, Stuttgart 2005, S. 202.

[55] Exactly when Roman Anti-Judaism began is a question of scholarly debate, however historian Hayim Hillel Ben-Sasson has proposed that the "Crisis under Caligula" (37–41) was the "first open break between Rome and the Jews".

[66] Implementation of these plans led to violent opposition, and triggered a full-scale insurrection with the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 CE),[67] assisted, according to Dio Cassius, by some other peoples, perhaps Arabs who had recently been subjected by Trajan.

Rather, the Jewish diaspora during this time period was created from various factors, including through the creation of political and war refugees, enslavement, deportation, overpopulation, indebtedness, military employment, and opportunities in business, commerce, and agriculture.

The success of mass-conversions is however questionable, as most groups retained their tribal separations and mostly turned Hellenistic or Christian, with Edomites perhaps being the only exception to merge into the Jewish society under Herodian dynasty and in the following period of Jewish–Roman Wars.

In 2006, a study by Doron Behar and Karl Skorecki of the Technion and Ramban Medical Center in Haifa, Israel demonstrated that the vast majority of Ashkenazi Jews, both men and women, have Middle Eastern ancestry.

Goldstein argues that the Technion and Ramban mtDNA studies fail to actually establish a statistically significant maternal link between modern Jews and historic Middle Eastern populations.

"[114][115] "The most parsimonious explanation for these observations is a common genetic origin, which is consistent with an historical formulation of the Jewish people as descending from ancient Hebrew and Israelite residents of the Levant."

One set of genetic characteristics which is shared with modern-day Europeans and Central Asians is most prominent in the Levant amongst "Lebanese, Armenians, Cypriots, Druze and Jews, as well as Turks, Iranians and Caucasian populations".

Fernández noted that this observation clearly contradicts the results of the 2013 study led by Costa, Richards et al. that suggested a European source for 3 exclusively Ashkenazi K lineages.

[120] Sephardic Jews subsequently migrated to North Africa (Maghreb), Christian Europe (Netherlands, Britain, France and Poland), throughout the Ottoman Empire and even the newly discovered Latin America.

A small number of Sephardic refugees who fled via the Netherlands as Marranos settled in Hamburg and Altona Germany in the early 16th century, eventually appropriating Ashkenazic Jewish rituals into their religious practice.

Karaite Jews rely on the use of sound reasoning and the application of linguistic tools to determine the correct meaning of the Tanakh; while Rabbinical Judaism looks towards the Oral law codified in the Talmud, to provide the Jewish community with an accurate understanding of the Hebrew Scriptures.

[citation needed] Jews of Israel comprise an increasingly mixed wide range of Jewish communities making aliyah from Europe, North Africa, and elsewhere in the Middle East.

The Jewish traveler, Benjamin of Tudela, speaking of Kollam (Quilon) on the Malabar Coast, writes in his Itinerary: "...throughout the island, including all the towns thereof, live several thousand Israelites.

[141] Scholars such as Harry Ostrer and Raphael Falk believe this indicates that many Jewish males found new mates from European and other communities in the places where they migrated in the diaspora after fleeing ancient Israel.

Israel Bartal, then dean of the humanities faculty of the Hebrew University, countered "that no historian of the Jewish national movement has ever really believed that the origins of the Jews are ethnically and biologically 'pure.'

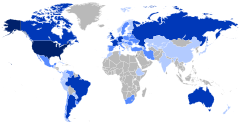

a.^ Austria, Czech republic, Slovenia b.^ Albania, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Macedonia, Syria, Turkey c.^ Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia d.^ Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), Belarus, Moldova, Russia (including Siberia), Ukraine.