Jewish emancipation

Many became active politically and culturally within wider European civil society as Jews gained full citizenship.

In 1251 Béla IV of Hungary gave the Jews of the Kingdom equal rights and legal protection, which was an important step towards Jewish emancipation.

But, it was not until the revolutions of the mid-19th century that Jewish political movements would begin to persuade governments in Great Britain and Central and Eastern Europe to grant equal rights to Jews.

[12] In English law and some successor legal systems there was a convention known as benefit of clergy (Law Latin: privilegium clericale) by which an individual convicted of a crime, through claiming to be a Christian clergyman (usually as a pretext; in most cases the defendant claiming benefit of clergy was a layperson) could escape punishment or receive a reduced punishment.

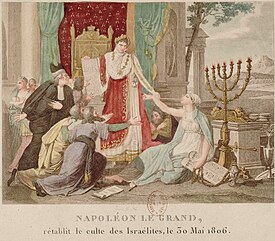

The early stages of Jewish emancipation movements were part of the general progressive efforts to achieve freedom and rights for minorities.

[15] In 1781, the Prussian civil servant Christian Wilhelm Dohm published the famous script Über die bürgerliche Emanzipation der Juden (English: On the Citizen Emancipation of the Jews).

"[17] A number of German states used the altered text version as legal grounds to reverse the Napoleonic emancipation of Jewish citizens.

[18] Although the movement was mostly successful; some early emancipated Jewish communities continued to suffer persisting or new de facto, though not legal, discrimination against those Jews trying to achieve careers in public service and education.

Those few states that had refrained from Jewish emancipation were forced to do so by an act of the North German Federation on 3 July 1869, or when they acceded to the newly united Germany in 1871.

[39] Thus, with emancipation, many Jews' relationships with Jewish belief, practice, and culture evolved to accommodate a degree of integration with secular society.

[45] Emancipation offered Jewish people civil rights and opportunities for upward mobility, and assisted in dousing the flames of widespread Jew-hatred (though never completely, and only temporarily).

[46][47] While this element of emancipation gave rise to antisemitic canards relating to dual loyalties, and the successful upward mobility of educated and entrepreneurial Jews saw pushback in antisemitic tropes relating to control, domination, and greed, the integration of Jews into wider society led to a diverse tapestry of contribution to art, science, philosophy, and both secular and religious culture.