Jews of Bilad el-Sudan

These Jewish communities continued to exist for hundreds of years but eventually disappeared as a result of changing social conditions, persecution, migration, and assimilation.

These communities were augmented by subsequent arrivals of Jews after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE, when 30,000 Jewish slaves were settled throughout Carthage by the Roman emperor Titus.

[1] The Septuagint,[2] and Jerome,[3] who was taught by Jews, and very often the Aramaic Targum on the Prophets, identify the Biblical Tarshish with Carthage, which was the birthplace of a number of rabbis who are mentioned in the Talmud.

As early as Roman times, Moroccan Jews had begun to travel inland in order to trade with groups of Berbers, most of whom were nomads who dwelt in remote areas of the Atlas Mountains.

Across the Atlas Mountains, the legendary Queen Kahina led a tribe of seventh-century Berbers, Jews, and other North African ethnic groups in battle against encroaching Islamic warriors.

In the 10th century, as the social and political environment in Baghdad became increasingly hostile to Jews, many Jewish traders who lived and worked there moved to the Maghreb, particularly to Tunisia.

According to certain local Malian history, an account in the Tarikh al-Sudan may have recorded the first Jewish presence in West Africa which coincided with the arrival of the first Zuwa ruler of Koukiya and his brother, who settled near the Niger River.

Manuscript C of the Tarikh al-fattash describes a community called the Bani Israeel that in 1402 CE existed in Tindirma, possessed 333 wells, and had seven leaders: It is also stated that they had an army of 1500 men.

[8] In the 14th century, many Moors and Jews, who were fleeing persecution in Spain, migrated south to the Timbuktu area, which was part of the Songhai Empire at that time.

In 1492, Askia Muhammad I came to power in the previously tolerant region of Timbuktu and decreed that Jews must convert to Islam or leave; Judaism became illegal in Mali, as it did in Catholic Spain that same year.

Rabbi Sarur also states that their settlement in the Sahara dates from the end of the 7th century (Muslim chronology) when 'Abd al-Malik ascended the throne and conquered as far as Morocco.

Other accounts place a group of "Arabs" driven to Ajaj as being identified with the Mechagra mentioned by Erwin von Bary,[14] among whom a few Jews are said still to dwell there.

Victor J. Horowitz[15] also speaks of many free tribes in the desert regions who are Jews by origin, but who have gradually thrown off Jewish customs and have apparently accepted Islam.

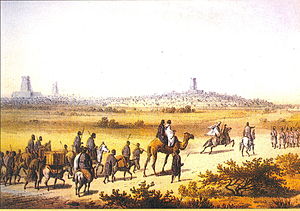

At the time of Rabbi Serour's bold enterprise, direct trade relations with the interior of west Africa (then known to them as Sudan) were monopolized by Muslim merchants.

[18] As a Jew, he couldn't set up his trading business, so he appealed to the regional ruler, who at that time was a Fulani Emir, and negotiated dhimmi, or protected people status.

During the early 19th century, Jews also came to settle in Santo Antão where there are still traces of their influx in the name of the village of Sinagoga, located on the north coast between Ribeira Grande and Janela, and in the Jewish cemetery at the town of Ponta da Sol.

A final chapter of Jewish history in Cape Verde took place in the 1850s when Moroccan Jews arrived, especially in Boa Vista and Maio for the hide trade.

This extraordinary "discovery" was made a by a young Malian historian, Ismaël Diadié Haïdara, a member of the Kati clan, and author of several books, including L'Espagne musulmane et l'Afrique subsaharienne (1997), and Les Juifs de Tombouctou (1999).