Jiajing Emperor

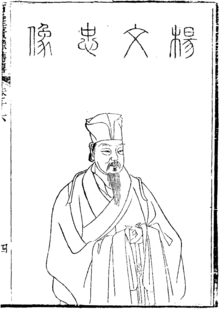

However, when the Zhengde Emperor died without an heir, the government, led by Senior Grand Secretary Yang Tinghe and the Empress Dowager Zhang, chose him as the new ruler.

Within the West Park, he surrounded himself with a group of loyal eunuchs, Taoist monks, and trusted advisers (including Grand Secretaries and Ministers of Rites) who assisted him in managing the state bureaucracy.

Before the death of the Zhengde Emperor, Grand Secretary Yang Tinghe, who was effectively leading the Ming government, had already begun preparations for the accession of Zhu Houcong.

Five days prior to the Zhengde Emperor's death, an edict was issued ordering Zhu Houcong to end his mourning and officially assume the title of Prince of Xing.

[19] During the dispute, the Jiajing Emperor asserted his independence from the Grand Secretaries and made decisions based on his own judgment, rather than consulting with them or simply approving their proposals.

Two years later, during civil service examinations, he asked candidates why there was still poverty in the country despite his efforts to faithfully follow Confucian teachings and observe ceremonies.

During the first phase of his reign, the Jiajing Emperor placed great importance on ceremonies, which were seen as essential in maintaining order and promoting a sense of superiority over non-Chinese peoples, according to Confucian beliefs.

[38] However, during Xia Yan's dominance in the Grand Secretariat, the emperor withdrew from the Forbidden City to the West Park, neglecting his public duties but still maintaining control over the government.

During this time, Ming China used military force to intimidate neighboring countries, successfully in the case of Đại Việt, but falling in the attempt to recapture Ordos, resulting in Xia Yan's death in 1548.

After the fall of Yan Song in 1562, the emperor's interest in good governance was rekindled under the influence of the capable and energetic Grand Secretary, Xu Jie.

[44] When the emperor had fallen asleep in one of his concubines' quarters, a serving girl led several palace women to start strangling him with a silk cord.

In 1527, ministers and Grand Secretaries Gui E, Fang Xianfu (方獻夫), Yang Yiqing, and Huo Tao (霍韜) proposed stricter regulations for the establishment of new Taoist and Buddhist temples and monasteries.

In 1528, the worst drought of the entire Ming era hit Zhejiang, Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Hubei,[60] resulting in the death of half of the population in some areas of Henan and Jiangnan.

In 1522, Yang Tinghe took decisive action by cutting off payments to 148,700 supernumerary and honorary officers and officials, resulting in an annual reduction of 1.5 million shi of grain in state expenditure.

He argued that the cost of reconstructing palaces, ceremonial altars, and temples had already reached 6 million liang (224 tons) of silver since the beginning of the Jiajing Emperor's reign, and that he did not have the means to sustain such a pace of construction.

The Ministry of Revenue attempted to address this issue by implementing stricter monitoring of income and expenses, as well as requiring final accounts to be presented at the end of each year.

The cost of maintaining military garrisons on the northern border doubled, and the state faced additional financial burdens due to the earthquake of 1556 and the fire that destroyed three audience palaces and the southern gate of the Forbidden City in 1557.

The local authorities were exhausted and lacked the resources to deal with floods and crop failures, and the government did not respond until the situation became dire and refugees, along with epidemics, appeared on the streets of Beijing.

The Jiangzhou school, led by figures such as Luo Hongxian, Zuo Shouyi (鄒守益), Ouyang De (歐陽德), and Nie Bao (聶豹), provided the most accurate interpretation of Wang's ideas.

He initially considered military action, but local authorities in Guangdong objected, arguing that the Viets had not crossed the border and the outcome of their civil war was uncertain.

In an attempt to avert an invasion in 1540, Mạc Thái Tông ceded disputed border territories to the Ming Empire and accepted the subordinate status of his state.

[107] This event left the Jiajing Emperor with the impression that his officials were more concerned with their personal interests than the well-being of the state and that they were unable to come up with a sound policy.

[114] The Ming troops were successful in defending against smaller raids, but they were unable to stop large-scale Mongol attacks involving tens of thousands of horsemen.

[62] The failure of the Beijing garrison to defend against the Mongol invasion in 1550 prompted reforms, resulting in the abolition of 12 divisions and the western and eastern special detachments.

These three corps were under the command of Qiu Luan, who held the title of Superintendent Commander-in-chief (縂督京營戎政; zongdu jingying rongzheng) and had gained recognition from the emperor for his role in the battles against the Mongols.

[119] In the late 15th century, Southeast China, particularly the Jiangnan region along the lower Yangtze River, experienced a surge in population, the development of communication networks, commercialization, and the growth of critical thinking.

[119] The Jiajing government attempted to address this issue by implementing repeated bans on private maritime trade, even going as far as prohibiting the construction of ships with two or more masts.

[37] He was often ill, failing to issue written orders after 11 November 1566 due to his poor health, and eventually died at his palace in the West Park on 23 January 1567.

Conflicts with officials centered around the role of the emperor, who was expected to act as an impartial judge in government discussions and carry out rituals in accordance with Neo-Confucian teachings.

As a result, profits from improved agricultural practices, industrial development, crafts, and trade remained in the hands of private individuals, while the state received only a small portion of them.