Administrative divisions of the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty of China administered territory using a hierarchical system of three descending divisions: circuits (dào 道), prefectures (zhōu 州), and counties (xiàn 縣).

Prefectures have been called jùn (郡) as well as zhōu (州) interchangeably throughout history, leading to cases of confusion, but in reality their political status was the same.

As Tang territories expanded and contracted, edging closer to the period of Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms, administrative records of these divisions became poorer in quality, sometimes either missing or altogether nonexistent.

Although the Tang administration ended with its fall, the circuit boundaries they set up survived to influence the Song dynasty under a different name: lù (路).

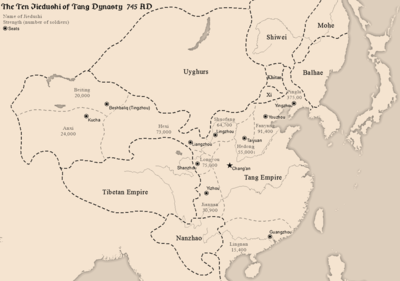

Emperor Taizong (r. 626−649) set up 10 "circuits" (道, dào) in 627 as areas for imperial commissioners to monitor the operation of prefectures, rather than as a direct level of administration.

These men handled the majority of daily government affairs and were the indispensable repositories of local knowledge, usage, and administrative precedent that their superiors relied upon.

Prefects, who typically employed a staff of only 57 men to administer 140,000 people, had to rely on the influence of these great clans to arbitrate disputes and preserve stability in the countryside.

These clans represented a distinctively local interest, but were not necessarily ungenerous or hostile to centralized power, for the courts' officers served as protectors for their possessions and passed a large portion of the tax burden on to their poorer neighbors.

However, in the years leading up to and following the An Lushan rebellion, changes in military organization enabled regional powers along the frontier to challenge the authority of the central government.

By the year 785 the empire had divided into roughly forty provinces or dào (道) and their governors allotted wider powers over subordinate prefectures and districts.

Although nominally subordinate to the Tang by accepting imperial titles, the garrisons governed their territories as independent fiefdoms with all the trappings of feudal society, establishing their own family dynasties through systematic intermarriage, collecting taxes, raising armies, and appointing their own officials.

The Tang court sometimes tried to intervene when a governor died or was driven out by one of the frequent mutinies, however the most it achieved was in securing promises of larger shares in tax revenue in exchange for affirming the successor's position.

While the Tang court officials argued that the Khitans' success was partially due to local collaboration, accounts imply that bitter feelings of perceived betrayal by the Chang'an administration lingered for decades.

After military defeats suffered against the Tibetans in 790 resulting in the complete loss of the Anxi Protectorate, the northwestern provinces around Chang'an subsequently became the Tang's true frontier and was garrisoned personally by the court armies at all times.

Deforestation in the region compounded the increasing soil erosion and desertification, which in turn reduced the amount of agricultural output in the area north and west of the capital.

Only in the second decade of the 9th century did Xianzong restore effective administration to the region after a series of campaigns, but by then Henan had been depopulated by constant warfare and strife, so that it too came to rely on southern grain.

In a sense, these autonomous provinces operated in many ways like miniature replicas of the Tang realm, with their own finances, foreign policy, and bureaucratic recruitment and selection procedures.

The cataclysmic Huang Chao rebellion was one of such vast magnitude that it shook the very foundations of the Tang empire, destroying it both internally as well as cutting off any pre-existing foreign contacts it had with the outside world.

After sacking the twin capitals Luoyang in 880 and Chang'an the following year, Huang Chao declared the founding of his Great Qí (大齊) dynasty.

Although the rebellion was finally defeated in 884, the court continued to face challenges posed by the warlords—officially military commissioners who held enormous regional power, including Li Maozhen in Fengxiang (Qizhou, Jingji 京畿), Li Keyong in Taiyuan (Bingzhou, Hedong), Wang Chongrong in Hezhong (Puzhou, Hedong), and Zhu Wen in Bianzhou, Henan.

Against this hopeless backdrop, the penultimate sovereign of Tang, Zhaozong, ascended the throne in 888, and although a man of lofty ambition, he remained throughout his reign a mere puppet in the machinations of court politics.

The great city of Chang'an was abandoned and its structures dismantled for their building materials, never again attaining the strategic importance and prestige it presided over for the last millennium.