Jim Crow economy

The primary differences of the Jim Crow economy, compared to a situation like apartheid, revolve around the alleged equality of access, especially in regard to land ownership and entry into the competitive labor market; however, those two categories often relate to ancillary effects in all other aspects of life.

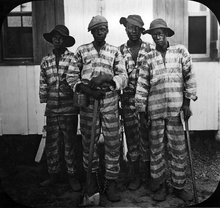

In the decades following the closure of the Freedmen's Bureau, in the South, black political participation was curtailed, the potential for acquiring new land was diminished, and ultimately Plessy v. Ferguson would usher in the Jim Crow era.

The results were less purchasers than had been hoped for, largely because the recently freed slaves did not have the material means to settle unimproved property, and only 4,000 of the 11, 633 total claims were registered by freedmen (Pope 1970:205).

Within the South, the Southern Homestead Act was seen as further punishment of attempting to secede; this was substantiated, by the repeal of 1876, when old enmities gave way to the promise of federal revenues (Gates 1940:311).

In the year following the end of the Civil War, black property owners accumulated approximately 10,000 acres (40 km2) of land, with a value of about $22,500; however, on average, African Americans in Georgia held a total wealth of less than $1 per person (Higgs 1982:728).

By expanding the defined territory of the South to 16 states (including Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia), in 1910, there were 175,000 black farm owners compared to 1.15 million white farm owners (Higgs 1973:150).

Thus, African Americans were laboring harder for lower crop returns, and putting the long-term productivity of their land in greater jeopardy (Ransom & Sutch 1973:142).

The South was much slower to industrialize; and, where predominantly white land owners retained large tracts of farmland, and where the population of black laborers remained high, agriculture continued as the economic base (Roscigno & Tomaskovic-Devey 1996:576).

In contrast to the antebellum urban settlement pattern, cities that rose to prominence in the postbellum years tended to be more highly segregated (Groves & Muller 1975:174).

Many growing cities and towns enacted their own Jim Crow ordinances; and, as they grew, they planned low-cost housing in areas with less access to public services, often using transportation corridors and natural features as buffer zones (Lee 1992:376-377).

Thus, another factor that is masked by the raw numbers is that the areas African Americans were moving into were already experiencing black unemployment rates of up to 40%, and where there were few employers that utilized unskilled and undereducated labor, at all (Wright 1987:175).

During the civil rights era, "economic coercion" was used to prevent participation, by denying credit, causing evictions, and canceling insurance policies (Bobo & Smith 1998:208).

In the most extreme analysis, the level of urban residential segregation, along the unidirectional economic dependency of African American communities, presents the possibility that they may be treated as a "national collectivity of internal colonies" (Bailey 1973:61).

The South was overwhelmingly based on agricultural production through the postbellum years, only seeing substantial increases in industrial manufacturing starting in the 1930s; and, for those who did not own farmland, the dominant forms of employment were: farm laborer, sharecropper, share-renter, and fixed renter.

Throughout this period there were some large landholders that used a set wage for farm laborers; however, the general lack of banks in the South made this arrangement problematic (Parker 1980:1024-1025).

Moreover, the tenant and the planter class landowner shared in the inherent risks of uncertain crop production; thus, external capital was invested in the merchant transporter who furnished staple goods in return, rather than in the agriculturalists directly (Parker 1980:1035).

By the last decade of the 19th century, the planter class had recovered from the Civil War enough to both keep Northern industrialist manufacturing interests out of the South, and to take the role of merchant themselves (Woodman 1977:546).

In any case, African Americans were often disadvantaged in obtaining work contracts outside the areas where they were personally known, due to employers not wanting to pay the cost of having to check on their claims of specific knowledge or skills germane to a task (Ransom & Sutch 1973:139).

From 1896, scientific racism was used as the basis for declaring black clients as substandard risks, which also affected the ability of black-owned insurance companies to secure capital to provide their own policies (Heen 2009:387).

Another economic impact of death is seen when the deceased does not have a will, and land is bequeathed to multiple people, under intestacy law, as tenancies in common (Mitchell 2000:507-508).

Frequently, the recipients of such property do not realize that if one of the common owners wishes to sell their share, then the entire estate can be put up for partition sale.

An economic analysis, conducted at the end of the 1970s, concluded that even if the freed slaves had been given the 40 acres and a mule that had been promised by the Freedman's Bureau, it still would not have been enough to entirely close the wealth gap between whites and blacks, to that point in time (DeCanio 1979:202-203).

As the recent decision of Pigford v. Glickman has shown, there are still race-based biases in way government entities like the United States Department of Agriculture decide how to disburse farm credit.

African American residential centralization, which started in the postbellum and Great Migration periods, continues to have a negative impact on employment rates (Herrington et al.:169).