Job Charnock

He was part of a private trading enterprise in the employ of the merchant Maurice Thomson between 1650 and 1653, but in January 1658 he joined the East India Company's service in Bengal, where he was stationed at Hoogly.

[citation needed] After four years at the factory he contemplated returning to England, but the Company persuaded him to stay on by promoting him to the position of chief factor in 1664.

[citation needed] Though he remained a devout Christian,[5] the story of his conversion and moral laxity was so widely believed that it became a cautionary tale in a later more puritanical age.

After some haggling due to difficulties with resentful colleagues who hoped to see him sent away to Madras, on 3 January 1679 the directors promoted him to the position of head at Cossimbazar, second in charge of the Company's operations in Bengal.

Cossimbazar was notorious as a smugglers' den, and when Charnock assumed his new post on Christmas Day 1680 it was over the objections of Streynsham Master, president at Madras, who oversaw the Company's operations in the whole Bay of Bengal.

Charnock was further irritated by the fact that members of Hedges' staff from Hooghly were regularly sabotaging their colleagues' work in Cossimbazar by poaching the local commodities.

Pursued by the nawab's troops, on 20 December 1686 he dropped down the river 27 miles (43 km) to Sutanuti, then "a low swampy village of scattered huts",[16] but a place well chosen for the purpose of defence.

[9] University librarian Prabodh Biswas writes that the ritual resembles the Sufi worship of the panch peer or "five saints", a custom which Charnock "is said to have adopted".

"[20] By 1686 the secret committee of the court of directors in London had decided the Company should establish a fortified settlement in Bengal, to resist what they regarded as arbitrary exactions and violent harassment by Mughal officials: we have no remedy left, But either to desert our Trade or we must draw that sord his Majesty hath intrusted us with to vindicate the Rights and Honour of the English Nation in India.

[15]Accordingly, in September 1688 the largest naval force the Company had ever assembled swept into the bay, with orders to blockade the ports and arrest the ships of the Grand Mughal, and, if this did not bring satisfaction, to take the town of Chittagong.

In Madras Charnock persuaded the reluctant council, over the objections of its president, his old opponent William Hedges, that Sutanuti was the best place to establish the headquarters in Bengal, because of its defensible position and its deep-water anchorage for the fleet.

[3] In March 1690, the Company received permission from Aurangzeb in Delhi to re-establish a factory in Bengal, and on 24 August 1690 Charnock returned to set up headquarters in the place he called Calcutta; the appointment of a new nawab ensured this agreement was honoured, and on 10 February 1691 an imperial grant was issued for the English to "contentedly continue their trade".

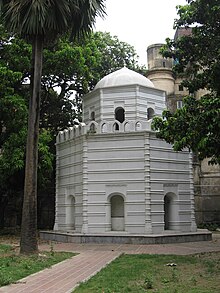

[16] Charnock died in Calcutta on 10 January 1692 (or 1693 according to an exhibition at the Victoria Memorial which points out that the 1692 date on his gravestone refers to an old calendar system by which the new year began in March), shortly after the death of his son.

Bengalensi dignissimum Anglorum Agens Mortalitatis suae exuvias sub hoc marmore deposuit, ut in spe beatae resurrectionis ad Christi judicis adventum obdormirent.

Qui postquam in solo non-suo peregrinatus esset diu reversus est domum suae aeternitatis decimo die 10th Januarii 1692.

We can see that Job mistrusted (though we apprehend justly) the wisdom of the orders given, especially as to the seizure of Chittagong; and his own notion of occupying Hijili as a fortified settlement showed what may doubtless seem strange ignorance of the sanitary condition of such a position.

The report added that there are multiple founders: Charnock, Eyre and Goldsborough, Lakshmikanta Majumdar, the Sett Bysack families, Gobindapur and Sabarna Choudhuries (who sold land to the English).

[34] The court argued that Charnock ought not to be regarded as the founder of Calcutta,[1] and ordered government authorities to purge his name from all textbooks and official documents containing the history of the founding story of the city.