Joe Hill (activist)

Joe Hill (October 7, 1879 – November 19, 1915), born Joel Emmanuel Hägglund and also known as Joseph Hillström,[1] was a Swedish-American labor activist, songwriter, and member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, familiarly called the "Wobblies").

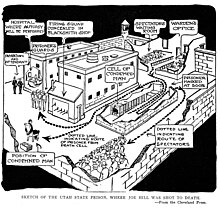

Following an unsuccessful appeal, political debates, and international calls for clemency from high-profile figures and workers' organizations, Hill was executed in November 1915.

The identity of the woman and the rival who supposedly caused Hill's injury, though frequently speculated upon, remained mostly conjecture for nearly a century.

[8] According to Adler, Hill and his friend and countryman Otto Appelquist were rivals for the attention of 20-year-old Hilda Erickson, a member of the family with whom the two men were lodging.

In his late teens-early twenties, Joel fell seriously ill with skin and glandular tuberculosis, and underwent extensive treatment in Stockholm.

[11] By this time using the name Joe or Joseph Hillstrom (possibly because of anti-union blacklisting), he joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) or Wobblies around 1910, when working on the docks in San Pedro, California.

He and Harry McClintock were Spellbinders for the IWW and would show up as they did at the Tucker Utah strike on June 14, 1913 (Salt Lake Tribune).

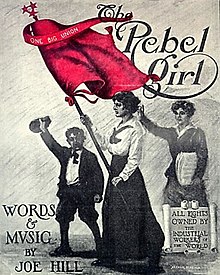

He coined the phrase "pie in the sky", which appeared in his song "The Preacher and the Slave" (a parody of the hymn "In the Sweet By-and-By").

On January 10, 1914, John G. Morrison and his son Arling were killed in their Salt Lake City grocery store by two armed intruders masked in red bandanas.

"[12] In a letter to the court, Hill continued to deny that the state had a right to inquire into the origins of his wound, leaving little doubt that the judges would affirm the conviction.

Chief Justice Daniel Straup wrote that his unexplained wound was "a distinguishing mark", and that "the defendant may not avoid the natural and reasonable inferences of remaining silent.

"[13] In an article for the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason, Hill wrote: "Owing to the prominence of Mr. Morrison, there had to be a 'goat' [scapegoat] and the undersigned being, as they thought, a friendless tramp, a Swede, and worst of all, an IWW, had no right to live anyway, and was therefore duly selected to be 'the goat'.

[16] Adler reports that evidence pointed to early police suspect Frank Z. Wilson, and cites Hilda Erickson's letter, which states that Hill had told her he had been shot by her former fiancé.

The bomb was discovered by a gardener, who found four sticks of dynamite, weighing a pound each, half hidden in a rut in a driveway fifty feet from the front entrance of the residence.

The dynamite sticks were bound together by a length of wire, fitted with percussion caps, and wrapped with a piece of paper matching the color of the driveway, a path used by Archbold in going to or from his home by automobile.

"[20] His last will, which was eventually set to music by Ethel Raim, founder of the group The Pennywhistlers, requested a cremation and reads:[21] My will is easy to decide For there is nothing to divide My kin don't need to fuss and moan "Moss does not cling to rolling stone"

The envelope, with a photo affixed, captioned "Joe Hill murdered by the capitalist class, Nov. 19, 1915", as well as its contents, was deposited at the National Archives.

Bragg did indeed swallow a small bit of the ashes with some Union beer to wash it down, and for a time carried Shocked's share for the eventual completion of Hoffman's last prank.

The main part was interred in the wall of a union office in Landskrona, a minor city in the south of the country, with a plaque commemorating Hill.

[26] On the night of November 18, 1990, the Southeast Michigan IWW General Membership Branch hosted a gathering of "wobs" in a remote wooded area at which a dinner, followed by a bonfire, featured a reading of Hill's last will, "and then his ashes were released into the flames and carried up above the trees.

[28] Hill's handwritten last will and testament was uncovered in the first decade of the 21st century by archivist Michael Nash of the Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Archives of New York University.

[29] Found in a box under a desk at the New York City headquarters of the Communist Party USA during a transfer of CPUSA archival materials to NYU, the document began with a couplet: "My will is easy to decide / For I have nothing to divide.