Jan Ladislav Dussek

Harold Schonberg wrote that he was the first pianist to sit at the piano with his profile to the audience, earning him the appellation "le beau visage."

As well as his many compositions for the piano, he also composed for the harp: his music for that instrument contains a great variety of figuration within a largely diatonic harmony, avoids chromatic passages.

Less well known to the general public than that of his more renowned Classical period contemporaries, his piano music is highly valued by many teachers and not infrequently programmed.

[citation needed] Franz Liszt has been called an indirect successor of Dussek in the composition and performance of virtuoso piano music.

[citation needed] His music remained popular to some degree in 19th-century Great Britain and the USA, some still in print, with more available in period editions online.

Jan Ladislav's mother, Veronika Dusíková (née Štěbetová), played the harp, an instrument, along with the piano, for which her son went on to write much music.

Jan Ladislav, the oldest of three children, was born on 12 February 1760 in the Bohemian town of Čáslav, where his father taught and played the organ.

While there he was introduced to a technician named Hessel, who had developed a keyboard version of the glass harmonica, an instrument Dussek went on to master.

[17] In a possibly apocryphal tale surrounding his departure, he was en route to play for Catherine when he found a ring, which he put on.

[18] After Dussek left St. Petersburg, he took a position as music director for Prince Antoni Radziwiłł in Lithuania, where he stayed about a year.

His departure from Lithuania may have been prompted by an affair he was rumored to have with the Prince's wife, the Princess of Thurn und Taxis.

[21] Another reviewer wrote, of a concert in Kassel, "He entranced all listeners with a slow, harmonic, and studiously modulated prelude and chorale.

He was in such demand that Davison, in an 1860 biographic sketch, noted that "he became one of the most fashionable professors of the day, and his lessons were both sought with avidity and remunerated at a rate of payment which knew no precedent except in the instance of John Cramer.

[31] His collaboration with Broadwood would continue to bear fruit when, in 1794, he also received the first 6-octave (CC-c4) piano[32] I am happy to inform you that you have an upstanding, polite, and musically gifted son.

In the spring of 1791, Dussek appeared in a series of concerts, a number of which featured Sophia, the young daughter of music publisher Domenico Corri.

In an account of uncertain veracity, it was reported that Sophia, who had fallen in love with another man, asked Dussek for money to repair her harp.

She then used the money to leave the house, removing her belongings in her harp case, and claiming to have left for dinner with a female friend.

"[40] Though the plot may be considered of a nature rather too gloomy for an after-piece, it possesses a considerable degree of interest ... Mr. Dussek, in the music which is entirely new, has displayed a complete knowledge of the principles of the art.

The melody throughout is natural and the choruses are, without exception, as perfect specimens as we can find in the works of the theatrical composers of the present day.

Dussek and Corri managed to convince the librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte to lend them money to cover their debts.

[43] According to Louis Spohr, Dussek was the first to turn the piano sideways on the stage "so that the ladies could admire his handsome profile.

When Prince Louis Ferdinand was killed in the Battle of Saalfeld, Dussek wrote the moving Sonata in F sharp minor, Elégie harmonique, Op.

[44] In 1807, despite his earlier affiliation with Marie Antoinette, Dussek returned to Paris in the employ of Talleyrand, the powerful French foreign minister.

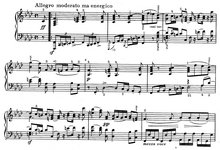

[44] Many of his works are strikingly at odds with the prevailing late Classical style of other composers of the time like Beethoven, Hummel, and Schubert.

The evolution of style found in Dussek's piano writing suggests he pursued an independent line of development, one that anticipated but did not influence early Romanticism.

[citation needed] Dussek was one of a number of foreign-born composers, including Muzio Clementi and John Field, who contributed significantly to the development of a distinct "London" school of pianoforte composition.

Joseph Haydn, for instance, composed his famous E-flat sonata after playing a piano of greater range lent to him by Dussek.

[47] Much of Dussek's piano writing drew upon the more modulable and powerful tonal qualities and greater keyboard range of English-manufactured pianofortes.

29, published in 1795, starts with an introductory Larghetto in 3/8 time, a solemn thematic declamation that is unique to the classical concerto.

He wrote a modest number of vocal works, include 12 songs, a cantata, a mass, and one opera, The Captive of Spilberg.