John Bardeen

[13] In October 1945, Bardeen began work at Bell Labs as a member of a solid-state physics group led by William Shockley and chemist Stanley Morgan.

Other personnel working in the group were Walter Brattain, physicist Gerald Pearson, chemist Robert Gibney, electronics expert Hilbert Moore and several technicians.

The group was at a standstill until Bardeen suggested a theory that invoked surface states that prevented the field from penetrating the semiconductor.

This led to several more papers (one of them co-authored with Shockley), which estimated the density of the surface states to be more than enough to account for their failed experiments.

The pace of the work picked up significantly when they started to surround point contacts between the semiconductor and the conducting wires with electrolytes.

Moore built a circuit that allowed them to vary the frequency of the input signal easily and suggested that they use glycol borate (gu), a viscous chemical that did not evaporate.

Finally, they began to get some evidence of power amplification when Pearson, acting on a suggestion by Shockley,[16] put a voltage on a droplet of gu placed across a p–n junction.

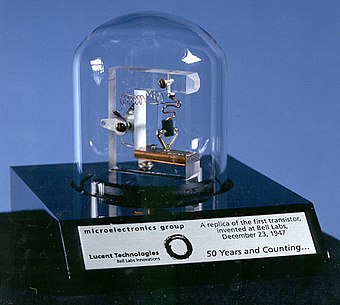

On December 23, 1947, Bardeen and Brattain were working without Shockley when they succeeded in creating a point-contact transistor that achieved amplification.

[18] Shockley publicly took the lion's share of the credit for the invention of the transistor; this led to a deterioration of Bardeen's relationship with him.

Shockley eventually infuriated and alienated Bardeen and Brattain, essentially blocking the two from working on the junction transistor.

[20][21] The "transistor" (a portmanteau of "transconductance" and "resistor") was 1/50 the size of the vacuum tubes it replaced in televisions and radios, used far less power, was far more reliable, and it allowed electrical devices to become more compact.

[8] In his later life, Bardeen remained active in academic research, during which time he focused on understanding the flow of electrons in charge density waves (CDWs) through metallic linear chain compounds.

[26] However, experiments reported in 2012[27] show oscillations in CDW current versus magnetic flux through tantalum trisulfide rings, similar to the behavior of superconducting quantum interference devices (see SQUID and Aharonov–Bohm effect), lending credence to the idea that collective CDW electron transport is fundamentally quantum in nature.

[33] At the Nobel Prize ceremony in Stockholm, Brattain and Shockley received their awards that night from King Gustaf VI Adolf.

The matter was further discussed on the 8th International Conference on Low Temperature Physics held September 16 to 22, 1962 at Queen Mary University of London.

After an intense debate both men were unable to reach a common understanding, and at points Josephson repeatedly asked Bardeen, "Did you calculate it?

"[35]: 225–226 In 1963, experimental evidence and further theoretical clarifications were discovered supporting the Josephson effect, notably in a paper by Philip W. Anderson and John Rowell from Bell Labs.

[38] After this, Bardeen came to accept Josephson's theory and publicly withdrew his previous opposition to it at a conference held in August 1963.

[34] Bardeen gave much of his Nobel Prize money to fund the Fritz London Memorial Lectures at Duke University.

He also reasoned that the Nobel Committee had a predilection for multinational teams, which was the case for his tunneling nominees, each being from a different country.

Lillian Hoddeson said that because he "differed radically from the popular stereotype of 'genius' and was uninterested in appearing other than ordinary, the public and the media often overlooked him.

Bardeen died of heart disease at age 82 at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 30, 1991.

[51] Sony Corporation owed much of its success to commercializing Bardeen's transistors in portable TVs and radios, and had worked with Illinois researchers.

[53] At the time of Bardeen's death, then-University of Illinois chancellor Morton Weir said, "It is a rare person whose work changes the life of every American; John's did.

"[40] Bardeen was honored on a March 6, 2008, United States postage stamp as part of the "American Scientists" series designed by artist Victor Stabin.

[54] His citation reads: "Theoretical physicist John Bardeen (1908–1991) shared the Nobel Prize in Physics twice—in 1956, as co-inventor of the transistor and in 1972, for the explanation of superconductivity.