John Brown of Haddington

By his own intense application to study, before he was twenty years of age, he had obtained an intimate knowledge of the Latin, Greek, and Hebrew languages, with the last of which he was critically conversant.

[4] Having recovered from this illness, he had the good fortune to find a friend and protector in John Ogilvie, a shepherd venerable for age, and eminent for piety, who fed his flock among the neighbouring mountains.

This worthy individual was an elder of the parish of Abernethy, yet, though a person of intelligence and religion, was so destitute of education as to be unable even to read.

To supply his own deficiency, Ogilvie was glad to engage young Brown to assist him in tending his flock, and read to him during the intervals of comparative inaction and repose which his occupation afforded.

In consequence of this change, young Brown entered the service of a neighbouring farmer, who maintained a more numerous establishment than his former friend.

A new attack of fever in 1741 reawakened his conscience, and on his recovery he 'was providentially determined, during the noontide while the sheep which I herded rested themselves in the fold, to go and hear a sermon, at the distance of two miles, running both to and from it.

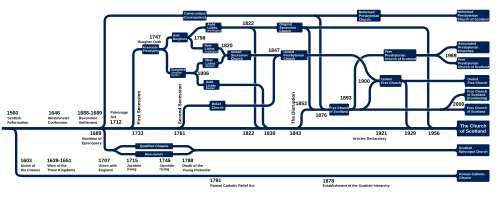

'[4] In the year 1733, four ministers of the Church of Scotland, among whom was Mr Moncrieff of Abernethy, declared a secession from its judicatures, alleging as their reasons for taking this step the following list of grievances; "The sufferance of error without adequate censure; the infringement of the rights of the Christian people in the choice and settlement of ministers under the law of patronage; the neglect or relaxation of discipline; the restraint of ministerial freedom in opposing mal-administration, and the refusal of the prevailing party to be reclaimed."

He accordingly prosecuted his studies with increasing ardour and diligence, and began to attain considerable knowledge of Latin and Greek.

These acquisitions he made entirely without aid from others, except that he was able occasionally to snatch an hour when the flocks were folded at noon, in order to seek the solution of such difficulties as his unaided efforts could not master, from two neighbouring clergymen the one Mr Moncrieff of Abernethy, who has just been mentioned as one of the founders of the Secession, and the other Mr Johnston of Arngask, father of the late venerable Dr Johnston of North-Leith; both of whom were very obliging and communicative, and took great interest in promoting the progress of the studious shepherd-boy.

A companion agreed to take charge of his sheep for a little, so setting out at midnight, he reached St. Andrews, twenty-four miles distant, in the morning.

[4] Before he was twenty years of age, he had obtained an intimate knowledge of the Latin, Greek, and Hebrew languages, with the last of which he was critically conversant.

[4] The next few years saw Brown work as a pedlar and a schoolmaster, with an interlude as a volunteer soldier in defence against the Jacobites in the Forty-Five rebellion.

He would commit to memory fifteen chapters of the Bible as an evening exercise after the labours of the day, and after such killing efforts, allow himself but four hours of repose.

Two bodies were formed, called the Burghers and the Anti-burghers, of whom the first maintained that it was, and the second that it was not, lawful to take the burgess oath in the Scottish towns.

Brown adhered to the more liberal view, and now began to prepare himself for the ministry, he studied theology and philosophy in connection with the Associate Burgher Synod under Ebenezer Erskine of Stirling, and James Fisher of Glasgow.

His ministerial duties were very hard, for during most of the year he delivered three sermons and a lecture every Sunday, whilst visiting and catechising occupied many a weekday.

A great deal of work, but no salary, was attached to this office; the students studied under Brown at Haddington during a session of nine weeks each year (McKerrow's History, p. 787).

The stern self-denial that was a frequent feature in the early Scottish household enabled him to bring up a large family, and meet all the calls of necessity and duty on this income.

Although he says that 'few plays or romances are safely read, as they tickle the imagination, and are apt to infect with their defilement,' so that 'even the most pure, as Young, Thomson, Addison, Richardson, bewitch the soul, and are apt to indispose for holy meditation and other religious exercises,' and although he eagerly opposed the relaxation of the penal statutes against Roman catholics, he was, in regard to many things, not at all a narrow-minded man.

His creed was to him a matter of such intense conviction, that nothing seemed allowable that tended in any way to oppose it or distract attention from its solemn doctrines.

A widely current story affirms that David Hume heard him preach, and the 'sceptic' was so impressed that he said, 'That old man speaks as if the Son of God stood at his elbow.'

John Swanston of Kinross, Professor of Divinity under the Associate Synod, Mr Brown was elected to the vacant chair.

His public prelections were directed to the two main objects, first, of instructing his pupils in the science of Christianity, and secondly, of impressing their hearts with its power.

The system of Divinity which he was led, in the course of his professional duty, to compile, and which was afterwards published, is perhaps the one of all his works which exhibits most striking proofs of precision, discrimination, and enlargement of thought; and is altogether one of the most dense, and at the same time perspicuous views which has yet been given of the theology of the Westminster Confession.

His contacts with three famous contemporaries have been documented: Brown's labours finally ruined his health, which during the last years of his life was very poor.

[18] The Self Interpreting Bible, first published in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1778, was Brown's most significant work, and it remained in print (edited by others), until well into the twentieth century.