John Colter

Though party to one of the more famous expeditions in history, Colter is best remembered for explorations he made during the winter of 1807–1808, when he became the first known person of European descent to enter the region which later became Yellowstone National Park and to see the Teton Mountain Range.

[3] John Colter, along with George Shannon and Patrick Gass, joined the expedition while Lewis was waiting for the completion of their vessels in Pittsburgh and nearby Elizabeth, Pennsylvania.

In one instance, Colter was handpicked by Clark to deliver a message to Lewis, waylaid at a Shoshone camp, concerning the impracticability of following a route along the Salmon River.

Through non-verbal peace symbols and communication, Colter was able to persuade the Flatheads to abandon their search for two Shoshones who had stolen 23 head of horses and accompany him to the expedition's camp.

There, they encountered Forrest Hancock and Joseph Dickson, two frontiersmen who were headed into the upper Missouri River country in search of beaver furs.

On August 13, 1806, Lewis and Clark permitted Colter to be honorably discharged almost two months early so that he could lead the two trappers back to the region they had explored.

In 1807, Colter's settlement was retracted after Congress passed a mandate supplying all members of the Corps of Discovery with doubled wages and land grants of 320 acres.

Colter, Hancock, and Dixon ventured into the wilderness with 20 beaver traps, a two-year supply of ammunition, and numerous other small tools gifted to them by the expedition such as knives, rope, hatchets, and personal utensils.

After reaching a point where the Gallatin, Jefferson and Madison Rivers meet, known today as Three Forks, Montana, the trio managed to maintain their partnership for only about two months.

[8] However, Wyoming historian J.K. Rollinson asserts in a personal letter that he had met the stepson of one of Colter's companions, mostly likely Hancock's as Dixon is known to have left the region for Wisconsin in 1827.

Fleming reportedly remembered and passed on this detail as his stepfather asserted that during winter of 1806–1807, Colter had grown restless with taking shelter and ascended the canyon into the Sunlight Basin of modern-day Wyoming, which would make him the first known white man to have ever entered this region.

[2] Colter headed back toward civilization in 1807 and was near the mouth of the Platte River when he encountered Manuel Lisa, a founder of the Missouri Fur Trading Company, who was leading a party that included several former members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, towards the Rocky Mountains.

At the confluence of the Yellowstone and Bighorn Rivers, Colter helped build Fort Raymond and was later sent by Lisa to search out the Crow Indian tribe to investigate the opportunities of establishing trade with them.

Colter reportedly visited at least one geyser basin, though it is now believed that he most likely was near present-day Cody, Wyoming, which at that time may have had some geothermal activity to the immediate west.

Colter arrived back at Fort Raymond, and few believed his reports of geysers, bubbling mudpots and steaming pools of water.

It is commonly believed that Colter's Hell referred to the region of the Stinking Water, now known as the Shoshone River, particularly the section running through Cody.

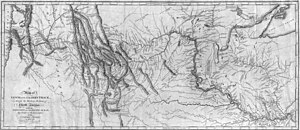

Clark's original field sketches, drawn on numerous separate sheets that traced the flows of principal rivers as opposed to traditional rectangular or square maps, were shown to President Jefferson in 1807 and did not include Colter's Route, as he was still traveling at the time.

[2] A version of these original field maps was produced in 1810 by Clark and Nicholas Biddle so that inaccurate recordings of latitude and longitude could be corrected by astronomer and mathematician Ferdinand Hassler.

Several unexplained geographical discrepancies were printed on the 1814 map, including the Big Horn Mountains and basin being drawn about two times too large, an error believed to be Clark's.

The Native American, surprised by the suddenness of the action, and perhaps at the bloody appearance of Colter, also attempted to stop; but exhausted with running, he fell whilst endeavouring to throw his spear, which stuck in the ground, and broke in his hand.

Continuing his run with a pack of Indians following, he reached the Madison River, five miles (8.0 km) from his start, and hiding inside a beaver lodge, escaped capture.

The stereotypes of reclusive frontier mountain men may be thanks to Nicholas Biddle's written characterizations of Colter, which paint him a man easily beguiled by the trapping prospects of the wilderness and intimidated by the possibility of returning to regular society.

Traditionally, it is thought that Lewis and Clark's Expedition played a major role in heightening tensions between white explorers and the Blackfeet Indians.

If the stone is an actual carving made by Colter, in the year inscribed, it would coincide with the period he is known to have been in the region, and that he did cross the Teton Range and descend into Idaho, as descriptions he dictated to William Clark indicate.

A log with the carved initials "J C" underneath a large X was discovered by Philip Ashton Rollins near Coulter Creek, a coincidentally named stream of no relation to Colter.